With an eye to the poetic truth beyond this practical fact, bridging the art of legends with her own art, she adds:

She saw how, in recurring across wildly different cultures and epochs only slightly altered in guise, they hold up a mirror to the childish vanity of our exceptionalism, reminding us that the human being “is a strangely alike animal.”

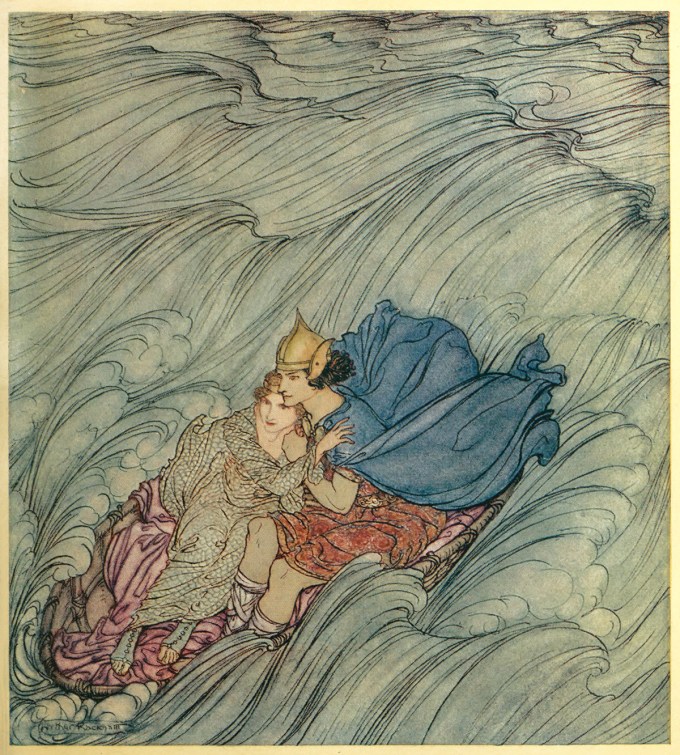

A century before science illuminated just how shaped by place the human animal is — and how much, therefore, our cosmogonies are shaped by our native landscapes — Amy Lowell devoured dozens of anthropology, ethnography, geography, and natural history books to achieve maximum fidelity to the authentic habitats of the myths that became her poetic matter.

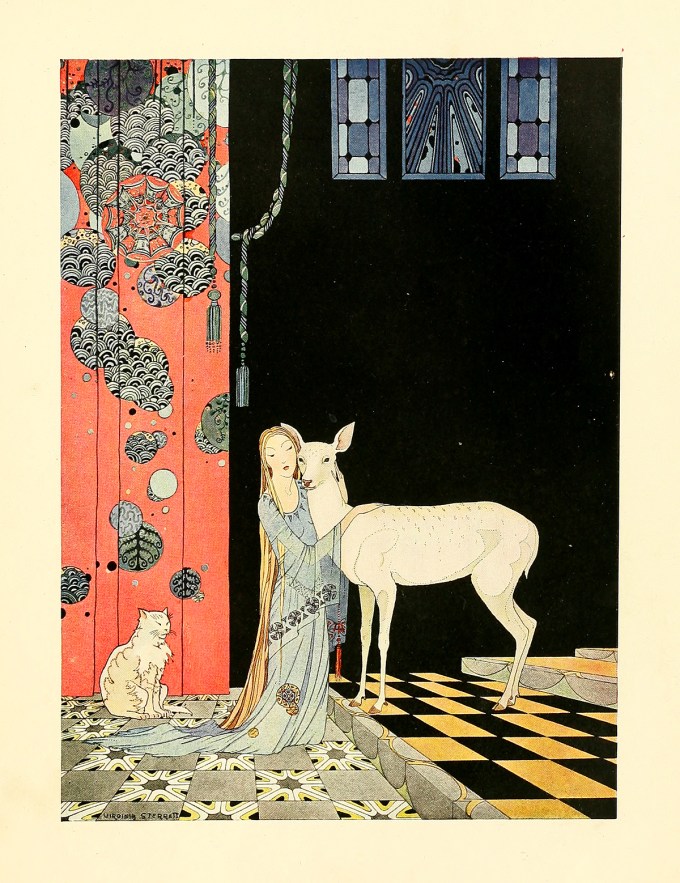

A poet is the most contradictory creature imaginable, he respects nothing and reveres everything, but what he loves he makes his own. And this then is just the touchstone of the true legend, it can be made over in any image, but always remains itself.

In 1921, D.H. Lawrence was staggered by a “strange and wonderful” book bursting with “primary, elemental forces, kinetic, dynamic — prismatic, tonic, the great, massive, active inorganic world, elemental, never softened by life, that hard universe of Matter and Force where life is not yet known, come to pass again.”

She writes in the preface:

Complement with the Nobel-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska on fairy tales and the importance of being scared, then revisit Michael Pollan on the surprising science behind the flying-witch legend

She saw how, in dealing with the most elemental human problems, they move us in the same ways they moved our ancestors, helping us see those things of perennial importance that hum beneath the surface urgencies of our time, of any time.

She fuses an ancient Chinese myth about a porcelain god with an 18th-century Chinese governor’s treatise on the production of pottery with the first scientific investigation of porcelain; she draws on the pioneering work of anthropologist Franz Boas and enthnomusicologist Frances Densmore to celebrate the authentic myths of Native Americans (then called “North American Indians”), in the authentic idioms of their native tongues, at a time when the American government was doing its best at erasure and assimilation; she reanimates a Roman legend about a garden statue, which she had first encountered on the pages of Robert Burton’s classic The Anatomy of Melancholy, published exactly three hundred years earlier. (Legends may be the supreme evidence of how seeds are planted and come abloom generations, centuries, civilizations later, migrating across coteries and countries and continents.)

Hence legends; they are bits of fact, or guesses at fact, pressed into the form of a story and flung out into the world as markers of how much ground has been travelled. If science be proven truth (and I believe it is), legends might be described as speculative or apprehended truth.

Lowell saw how, on the scale of the species, legends give us what fairy tales give us on the scale of the individual: tools for working out what we are and what we want.

A legend is something which nobody has written and everybody has written, and which anybody is at liberty to rewrite. It may be altered, it may be viewed from any angle, it may assume what dress the author pleases, yet it remains essentially the same because it is attached to the very fibres of the heart of man*. Civilization is the study of man about himself, his powers, limitations, and endurances; it is the slowly acquired knowledge of how he can best exist in company with his fellows on the planet called Earth. As man learns, he becomes conscious, first of an immense curiosity, and then of a measure of understanding, and, immediately after, of a desire to express both; and the simplest form of expression is by means of the tale or (hateful word!) allegory.

That book was Legends (public library | free ebook) by his passionate, visionary, cigar-smoking friend Amy Lowell (February 9, 1874–May 12, 1925), who changed the face of literature with her sharp-edged, kaleidoscopic imagist poems and her fierce patronage of other poets, Lawrence among them.

That inaccuracies from the point of view of the student of folk-lore have crept into the poems, I have no doubt, nor does it make any difference to me. The truth of poetry is imaginative, not literal, and it is as a poet that I have conceived and written my book.

What emerges from her poems is something “neither new, nor old” but “perennial,” coursing through which is “that curious substratum of reality, speculative or apprehended.”

In each of the book’s eleven epic poems, she varies the scales of geography and time to take on a different legend of a different culture — from China to Peru to New England — invoking the vivid natural landscape, climate, and wildlife of that region alongside its human stories.

With touching recognition of the limitations of even the most rigorous scholarship, she reflects: