Whitman knew this as he was recovering from a paralytic stroke and observing how infallibly nature can “bring out from their torpid recesses, the affinities of a man or woman with the open air, the trees, fields, the changes of seasons — the sun by day and the stars of heaven by night.” He intuited what science has since measurably demonstrated — that these affinities hold the key to what is brightest and most creative in us, for they are at bottom affinities with the freest parts of ourselves.

In nature, we go unfettered from the world’s illusory urgencies that so easily hijack the everyday mind and syphon our attention away from its best creative contribution to that very world and its needs. When we surrender to “soft fascination,” we are not running from the world but ambling back to ourselves and our untrammeled multitudes, free to encounter parts of the mind we rarely access, free to acquaint different parts with one another so that entirely novel connections emerge.

“Soft fascination” has an active counterpart in another state we experience most readily in nature: awe — that ultimate instrument of unselfing.

Paul writes:

Scientists theorize that the “soft fascination” evoked by natural scenes engages what’s known as the brain’s “default mode network.” When this network is activated, we enter a loose associative state in which we’re not focused on any one particular task but are receptive to unexpected connections and insights. In nature, few decisions and choices are demanded of us, granting our minds the freedom to follow our thoughts wherever they lead. At the same time, nature is pleasantly diverting, in a fashion that lifts our mood without occupying all our mental powers; such positive emotion in turn leads us to think more expansively and open-mindedly. In the space that is thus made available, currently active thoughts can mingle with the deep stores of memories, emotions, and ideas already present in the brain, generating inspired collisions.

Citing the work of the Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner — our epoch’s William James of awe — Paul writes:

James distinguished between two kinds of attention: “voluntary,” in which we willfully aim our focus at a particular object or activity with concerted effort, and “passive,” which approximates the Eastern notion of mindfulness — an effortless noticing of sensations and phenomena as they naturally arise within and around us, our focus drifting by its own accord from one stimulus to another as they emerge. James listed this “passivity” as one of the four qualities of mystical experiences. But it is also the most direct valve between the mystical and the mundane — the type of attention that places us in our most creative states.

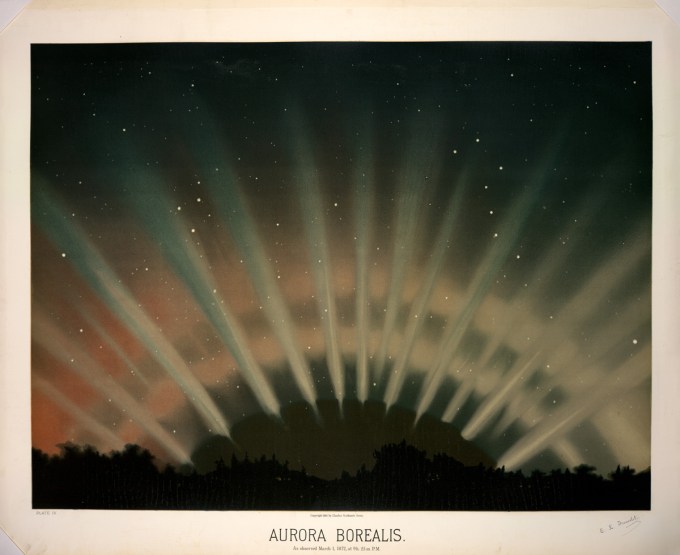

The experience of awe, Keltner and other researchers have found, prompts a predictable series of psychological changes. We become less reliant on preconceived notions and stereotypes. We become more curious and open-minded. And we become more willing to revise and update our mental “schemas”: the templates we use to understand ourselves and the world. The experience of awe has been called “a reset button” for the human brain. But we can’t generate a feeling of awe, and its associated processes, all on our own; we have to venture out into the world, and find something bigger than ourselves, in order to experience this kind of internal change.

In the epochs since James, scientists have termed this effortless attention “soft fascination.” It is at the root of our mightiest antidote to depression and our most generative mindsets, and it comes to us — or we to it — most readily in nature.

It is hardly surprising that in such states of awe, even the most nonreligious among us find the closest thing to spirituality. Without this reset button, how would we ever look at a dandelion and see the meaning of life?

Annie Murphy Paul devotes a portion of The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (public library) — her wonderful inquiry into the art-science of thinking with the whole world — to the science of this peculiar and singularly fertile state of mind, into which communion with the non-human world deposits us:

A generation later, in a different corner of Massachusetts, William James pioneered the study of attention with his then-radical (at least to the Western mind) declamation: “My experience is what I agree to attend to.”

One of the pleasurably fearsome things about awe is the radically new perspective it introduces. Our everyday experience does not prepare us to assimilate the gaping hugeness of the Grand Canyon or the crashing grandeur of Niagara Falls. We have no response at the ready; our usual frames of reference don’t fit, and we must work to accommodate the new information that is streaming in from the environment.

“In the street and in society I am almost invariably cheap and dissipated, my life is unspeakably mean,” Thoreau wrote in contemplating nature as a form of prayer — a clarifying force for the mind and a purifying force for the spirit, a lever for opening up the psyche’s civilization-contracted pinhole of concerns.

[Keltner] calls it an emotion “in the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear.”

Awe strikes the human animal indiscriminately of its age or era, its biometrics or identities. Its interleaving of pleasure and fear is at the heart of Virginia Woolf’s arresting account of a total solar eclipse, at the heart of the young Hans Christian Andersen’s climb of Vesuvius during an eruption, at the heart of the middle-aged Rachel Carson’s quiet, rapturous encounter with the moonlit tide, at the heart of what impelled Rockwell Kent toward “the cruel Northern sea with its hard horizons at the edge of the world where infinite space begins,” at the heart of “the overview effect” that staggers astronauts in orbit.