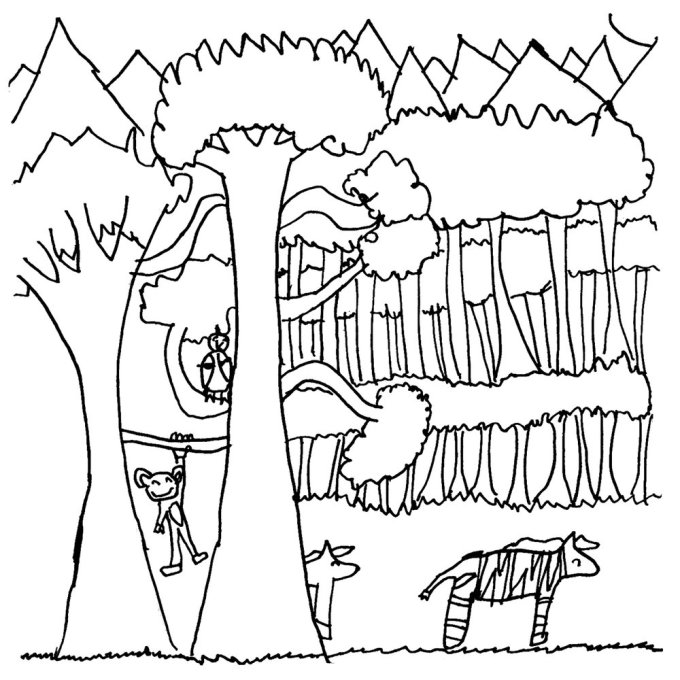

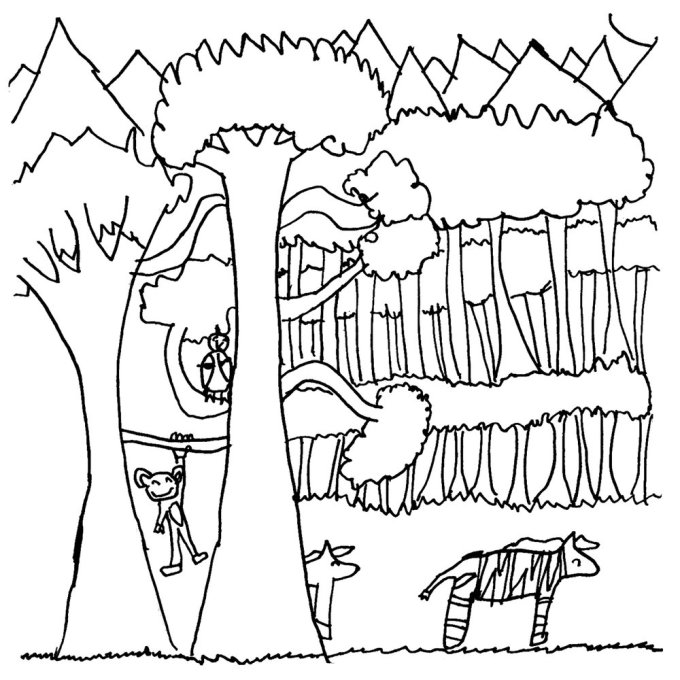

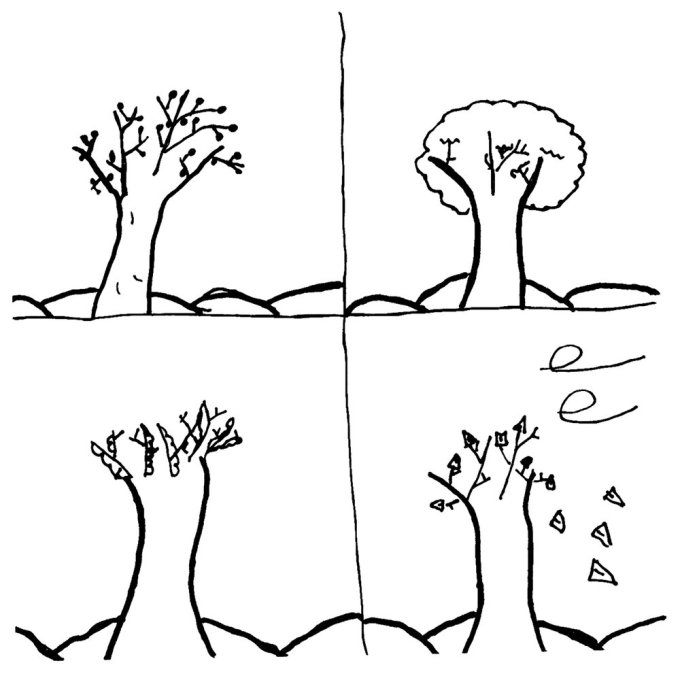

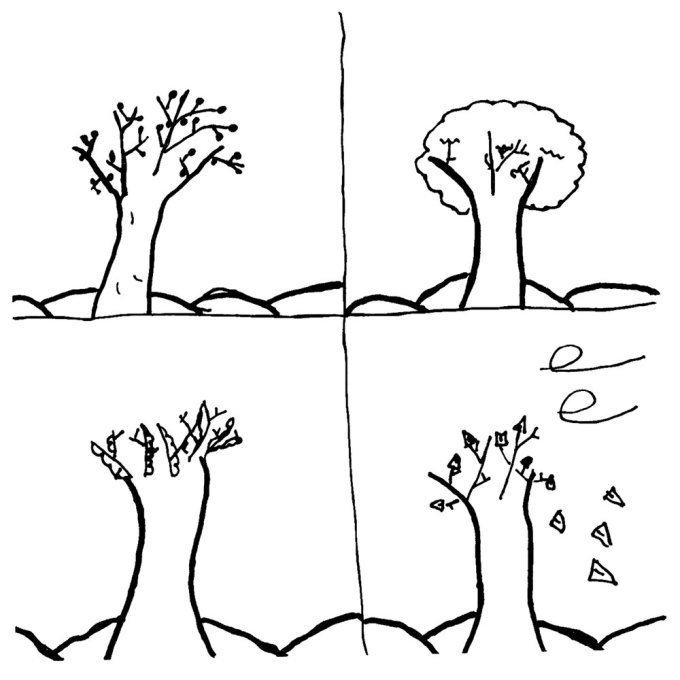

Most of all, there are the trees, abstracted and detailed, crowned and coniferous — a wilderness of ways of seeing, carrying a diverse forest of love into space. (Cue aschonut Leland Melvin reading Pablo Neruda’s love letter to Earth’s trees and Bruno Munari’s existentialist exercise in drawing a tree.) Because, as nine-year-old Dominic explains in his caption, trees are “one of the most inportent thing on earth they give us 02.”

The project shares something profound and everlasting with its inspiration: The Golden Record’s stated scientific aim — to compress, encode, and transmit information about our world to another — was the Trojan horse by which Sagan conquered NASA’s consent and achieved his true aim, which was the poetic: In a world falling apart in the Cold War, shuddering with the aftershocks of two World Wars, haunted by the assassinations of Dr. King and JFK and Gandhi, here was a mirror held up to humanity, inviting us to reflect on who we are and what we stand for, on the staggering beauty of this indivisible, irreplaceable Pale Blue Dot and our staggering capacity for the noticing of beauty, which is the language of love — that ultimate poetic truth of what makes us human.

It is this same truth, made all the truer and more tender by their openhearted innocence, that radiates from the children’s drawings.

DrawTogether was born early in the pandemic, in that Blakean way of complaining by creating: Amid the gasping incomprehension of the lockdown, as schools vanished from the cultural horizon and left parents around the world sequestered with their small humans and their large fears in every imaginable type of human habitat, Wendy — a longtime friend and occasional collaborator — began offering a daily series of free, simple, sunny-spirited online art lessons for kids, using drawing as a tool of social emotional learning and feeling-processing. Living proof of Ruskin’s impassioned Victorian case for drawing as a technique for paying attention. A way of seeing the world — both the inner world and the outer world — more clearly so that we may love it more deeply and live more unafraid of what we feel.

A generation and an epoch of discoveries later, the first cosmic gallery of art by the youngest members of our young species is launching into Earth orbit: a data-gathering NASA satellite carrying 100 drawings by children, depicting what they most love about life on Earth.

Punctuating the hundred-piece totality are some touching testaments to how impressionable kids are and how formed the human mind is by its cultural brine: cartoon characters, movie references, video game consoles, sports emblems.

“Out of the cradle onto the dry land… here it is standing… atoms with consciousness… matter with curiosity,” Richard Feynman wrote in his poetic ode to the wonder of life a decade before he won the Nobel Prize in Physics and two decades before these atoms of consciousness sent their most ambitious civilizational artwork toward the unknown reaches of the cosmos as the Golden Record sailed aboard NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, carrying our music, our photographs, and our longing for connection.

Inspired by the Golden Record, the project is a collaboration between illustrator and graphic journalist Wendy MacNaughton and NASA spacecraft systems designer Luke Idziak, winged by Wendy’s DrawTogether experiment-turned-icon — another improbable dream made real and resonant for millions with little more than passion and perseverance.

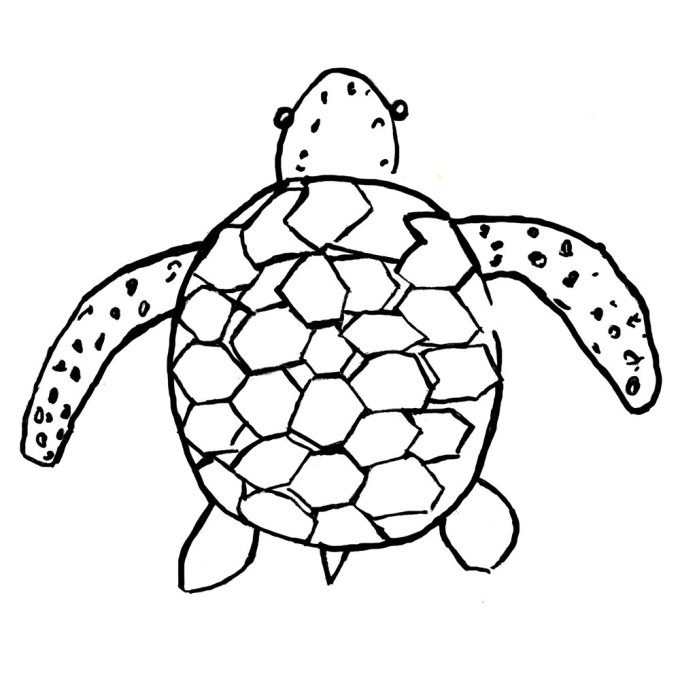

There are many people holding hands. There are flowers and turtles and a singing bird and a smiling octopus. Two different black-and-white curvatures colored by the mind’s eye into rainbows. The ocean and the sky. A multitude of mountains.

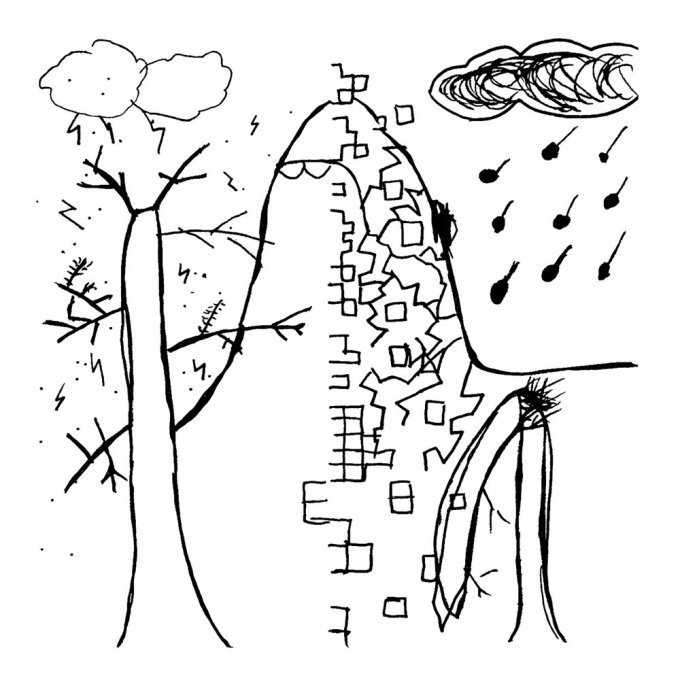

But what I find most moving is the developmental progression — by the time we get to the kids on the cusp of adolescence, the drawings are animated by the dual awareness that this wonder-full world is in peril and that it falls on them, these emissaries of tomorrow, to save it.

Thirteen-year-old Sylvia draws an exquisite geometric hummingbird to represent “the fragile beauty of our world.”

A fourth-grader named Amaya draws a butterfly in loving memory of her recently deceased grandmother, who loved “butterflys.”

But two things emerge as the most common objects of pride in life on Earth, incontestable as daybreak: nature and love. (Which are, in the end, a single thing.)

“Earth isn’t the best place right now,” writes thirteen-year-old Alma beneath a drawing of a smoking house and a denuded tree, “but we can work to fix it.” Their classmate Sebastian’s detailed drawing and pointed caption can spin a future President on her axis: “Taking notice isn’t enough we need to take action first.”

An improbable dream dreamt by Carl Sagan, rendered real on the wings of his passionate conviction that we are “a species endowed with hope and perseverance, at least a little intelligence, substantial generosity and a palpable zest to make contact with the cosmos.”

A miniature philosopher of nine named Jovie draws the infinity symbol over a heart and explains: “This is love. Love brings us together. It will never tear us apart. We’re stronger with love.”

Her classmate Rachelle offers a bittersweet reminder of the unselfconscious sincerity we learn to cower from as we grow up: “Dear NASA, I chose this drawing because I like nature, and it’s very pretty to look at and it calms me down.”