This vital relationship between creativity and connection has been tensed and twisted in the era of Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, where self-marketing so readily masquerades as “friend”-ship.

This mutually sustaining circle of creative kinship begins with a single lifeline of connection. Those of us who are lucky to have it in our own lives can easily identify it, always with a swell of gratitude. Miller writes:

Usually the artist has two life-long companions, neither of his own choosing… — poverty and loneliness. To have a friend who understands and appreciates your work, one who never lets you down but who becomes more devoted, more reverent, as the years go by, that is a rare experience. It takes only one friend… to work miracles.

No communication. No real intercommunication. No concern for the vital, subtle things which mean everything to a writer, painter or musician. We live in a void spanned by the most intricate and elaborate means of communication. Each one occupies a planet to himself. But the messages never get through.

Complement with David Whyte on the deepest meaning of friendship, Kahlil Gibran on the building blocks of meaningful connection, and this almost unbearably lovely vintage illustrated ode to friendship, then revisit Henry Miller on the measure of a life well lived and the value of and antidote to despair.

In 1950, epochs before our social media were but a glimmer in the eye of the possible, Henry Miller (December 26, 1891–June 7, 1980) reckoned with the seedling of our modern predicament in his meditation on art and life. Considering the downfall of art in his own epoch, when the age of publicity and mass media was just beginning to maim culture, he laments the state of the creative community:

How distressing it is to hear young painters talking about dealers, shows, newspaper reviews, rich patrons, and so on. All that comes with time — or will never come. But first one must make friends, create them through one’s work.

The sunshine of life springs from twin suns. We may call them love and art. We may call them connection and creativity. Both can take many forms. Both, if they are worth their salt and we ours, ask us to show up as our whole selves. Both are instruments of unselfing.

After honing his ideas on two decades of living, Miller took up the subject again in his uncommonly wonderful 1968 book To Paint Is to Love Again. In a passage just as hauntingly true of the compulsion for social media “likes,” he writes:

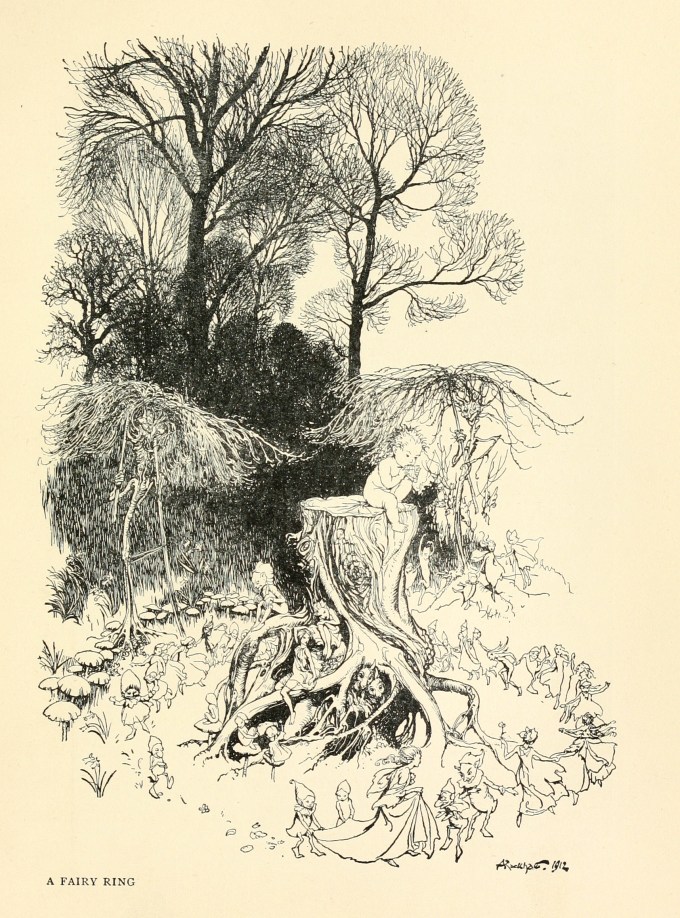

It is often in the cradle of friendship — a word not to be used carelessly — that our creative energies are strengthened and renewed. Through its tendrils, we find community — a place where our own creative work is reflected and refracted through that of others to cast a shimmering radiance of mutual magnification that borders on magic.