In 1634, Rembrandt painted his wife, Saskia, as Flora — the Roman goddess of flowers and spring. One large bloom droops over her left ear from the wreath crowning her head, dwarfing the other blossoms in scale and splendor — a single tulip, its silken petals aflame with stripes of red and white.

One crucial element of the beauty of the tulip that intoxicated the Dutch, the Turks, the French, and the English has been lost to us. To them the tulip was a magic flower because it was prone to spontaneous and brilliant eruptions of color. In a planting of a hundred tulips, one of them might be so possessed, opening to reveal the white or yellow ground of its petals painted, as if by the finest brush and steadiest hand, with intricate feathers or flames of a vividly contrasting hue… If a tulip broke in a particularly striking manner — if the flames of the applied color reached clear to the petal’s lip, say, and its pigment was brilliant and pure and its pattern symmetrical — the owner of that bulb had won the lottery. For the offsets of that bulb would inherit its pattern and hues and command a fantastic price. The fact that broken tulips for some unknown reason produced fewer and smaller offsets than ordinary tulips drove their prices still higher.

Every time I think of the story of the broken tulip, I think of Richard Feynman’s Ode to a Flower.

These tulips no longer exist. Today, their closest kin are known as Rembrandts. In the painter’s day, these living canvases of expressionist color transfixed the human imagination across cultures, casting a singular enchantment with their sudden and mysterious eruptions of contrasting color. Lay gardeners and professional horticulturalists all over Holland, France, and the Ottoman Empire planted tulip bulbs by the hundreds, by the thousands, hoping some would bloom in this inexplicable pattern of painterly stripes. On those rare and unbidden occasions when it happened, the tulip was said to “break.”

Because the history of our species is the history of humans longing for control of their fortunes and other humans exploiting this longing in the absence of knowledge and critical thought — from religions imbuing with mystical meaning yet-unexplained astronomical phenomena like comets and eclipses, to internet scammers — a new trade of charlatans emerged, promising surefire recipes (some involving pigeon droppings, others powdered plaster from the walls of old houses) to make the tulips break.

Gardeners went to extraordinary lengths to force tulips to break, their techniques still insentient to the newborn scientific method, still resonant with the echoes of alchemy haunting the atmosphere of their time: They would plant beds of white tulips, then sprinkle over the soil pigment powders of the hue they wished to see stripe the white petals, hoping rainwater would wash the bulb with pigment and somehow imprint the flower-to-be.

By the 1920s the Dutch regarded their tulips as commodities to trade rather than jewels to display, and since the virus weakened the bulbs it infected (the reason the offsets of broken tulips were so small and few in number), Dutch growers set about ridding their fields of the infection. Color breaks, when they did occur, were promptly destroyed, and a certain peculiar manifestation of natural beauty abruptly lost its claim on human affection.

The color of a tulip actually consists of two pigments working in concert — a base color that is always yellow or white and a second, laid-on color called an anthocyanin; the mix of these two hues determines the unitary color we see. The virus works by partially and irregularly suppressing the anthocyanin, thereby allowing a portion of the underlying color to show through. It wasn’t until the 1920s, after the invention of the electron microscope, that scientists discovered the virus was being spread from tulip to tulip by Myzus persicae, the peach potato aphid. Peach trees were a common feature of seventeenth-century gardens.

In an epoch when the microscope was still a novelty known to the very few and owned by the very privileged, when the discovery of submicroscopic non-bacterial pathogens was a quarter millennium away and the word ecology was two centuries from being coined, what the ardent gardeners and the ardent bulb-buyers and Rembrandt did not know was that a virus brought by another species was responsible for the rapturous breaking of the tulip; a virus the discovery of which vanquished the broken tulips and broke the spell their beauty had cast upon this ever-living, ever-dying world. Pollan explains the biomechanics behind the beauty:

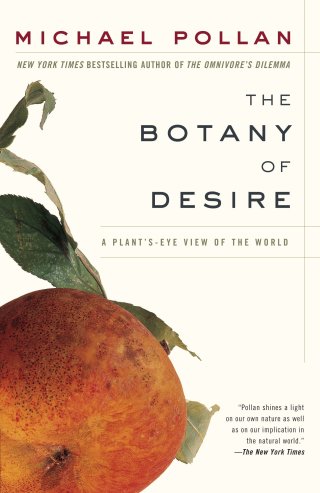

Couple this fragment of Pollan’s altogether enchanting The Botany of Desire with Emily Dickinson and the nonbinary botany of flowers, then revisit Sylvia Plath’s almost unbearably beautiful poem “Tulips.”

But what was really at play was something no one suspected, because no one had the reference-point nodes of understanding we call knowledge. What was really at play was an epochal intersection of science and culture, the story of which Michael Pollan tells with his signature enchanting erudition in The Botany of Desire (public library). He writes: