Or is it because the editors of, and referees for, these journals tend to render negative judgments about the submissions they see in these areas? (And if so, are these judgments about quality, or fit, or what?)

Once set up, this kind of data collection does not seem like it will be especially burdensome, and I don’t see a downside.

* Journals contacted: American Philosophical Quarterly, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, Ergo, Journal of the American Philosophical Association, Journal of Philosophy, Mind, Noûs, Philosophers’ Imprint, Philosophical Quarterly, Philosophical Review, Philosophical Studies, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, and Southern Journal of Philosophy. Not all of the journals have responded yet. If it turns out that one of them besides Ergo tracks submissions subject data, I will update the post indicating so.

As it turns out, most of them couldn’t—because they don’t keep track of this information.

It would be useful to know, as publication in such journals is, in practice, an important means of acquiring recognition, influence, promotions, jobs, and other professional goods in academic philosophy.

Is it some combination of these reasons? Or something else?

Editors of generalist journals influence philosophers’ perceptions of their discipline, playing a role, through their publication choices, in establishing what is considered mainstream or important. Getting a sense of the difference between what is submitted and what is published can help us better understand the nature and extent of that influence. As one editor wrote in a reply to my inquiry:

UPDATE: Brian Weatherson informs me that Philosophers’ Imprint began collecting this information last March, so the journal does not have a lot of it yet. When he has a chance, he will look into making it publicly available.

Might I suggest that journals start doing so?

Specialty journals and their editors, also have effects on career trajectories, publication strategies, as well as influences on philosophers’ perceptions of the subfields they cover, so I think the advice to start collecting subject and keyword data on submissions applies to them, too.

One thing needed in order to get clearer about this is data about the subjects of the submissions the journals get. So I contacted a number of highly-regarded generalist journals* to see if they could share their data about the areas, topics, or keywords of submitted manuscripts over the past several years.

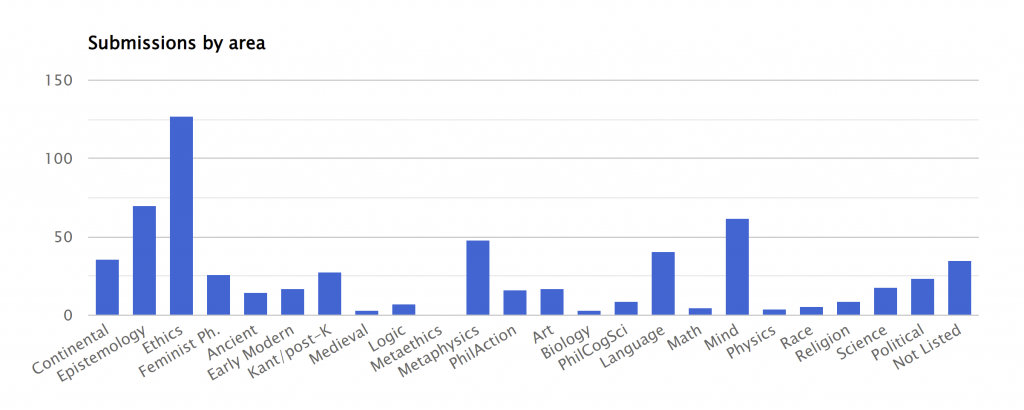

Of the journals that have gotten back to me so far, only one—Ergo—maintains this kind of data (along with other statistics, publicly available here). Below is a breakdown by area of submissions to the journal in 2021:

Related: Citation Patterns Across Journals, A History of Philosophy Journals Using Topic Modeling

With today’s technology, it should be fairly easy to collect, probably in an automated way, the subfields submissions are in and the keywords authors associate with their articles.

Some philosophical areas (and topics) don’t show up often in the pages of prestigious generalist philosophy journals. Is it because the journals don’t get many submissions in those areas? (And if so, why not?)

Shall we get this going, then? Comments welcome, particularly from journal editors.

The explanation could be useful to editors, too, who may have aspirations for broadening the range of subjects their journal covers. It could tell them, for example, about how their conception of breadth matches up with the actual breadth represented in submissions to their journal, or whether they ought to take efforts to encourage more submissions in certain areas (perhaps to counter what they consider to be an outdated picture of what kinds of philosophy their journal publishes), and so on.

I would be personally interested in the result… since I have tried to be open and encouraging towards increasing the range (in a few respects, including areas/topics) of our submissions. My informal sense is that this has improved, especially over the past few years. Still, maybe that’s just how I want to see the situation.

(Perhaps what we’ll learn is that, as Brian Weatherson (Michigan) discussed in a different context, “there’s no such thing as a generalist philosophy journal.” What would the upshot of that be?)

[Paint-chip rainbow by Hendra Lesmono, Andreas Junus, and Irawandhani Kamarga]

The actual explanation could influence authors’ publication strategies: if it turns out that a particular journal almost never receives submissions in, say, feminist theory, that may reasonably affect what practical implications an author considering submitting to it should draw from the fact that relatively little work in feminist theory has appeared in its pages.