Two studies have recently been conducted on the status of women in the philosophy profession, with one published by the British Philosophical Association (BPA) and the Society For Women In Philosophy (SWIP), and the other described in a post at the Canadian Philosophical Association (CPA) site.

“Women in Philosophy in the UK,” by Helen Beebee (Manchester) and Jennifer Saul (Waterloo) follows up, 10 years later, from their 2011 report, which was the first of its kind in the UK, and includes information about the status of women in philosophy, how it has changed over the past decade, and some recommendations for further steps.

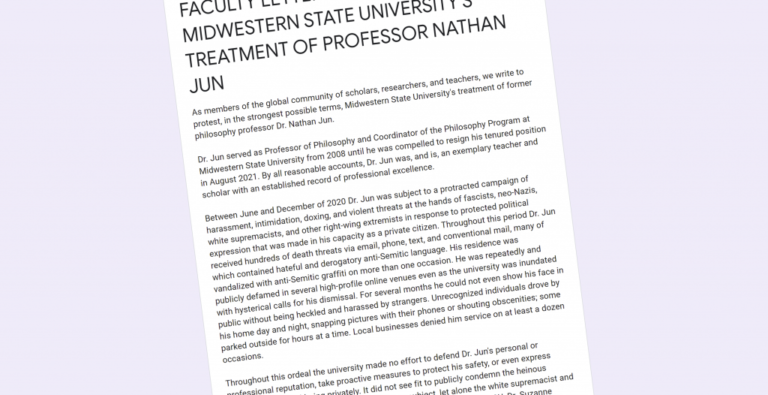

Answer: From a review of theoretical and empirical work on gender gaps in academia, we designed and implemented a survey…. The two most important factors turned out to be self-perceptions of brilliance and of belonging….

Overall, our findings provide (of course defeasible) evidence for the claim that students choose philosophy because they perceive a good fit between philosophy, qua requiring brilliance, and themselves, qua being brilliant, combative, systematizing, and indifferent towards “worldly rewards,” like family-life and money…. Fewer women than men show these self-perceptions and preferences.

-

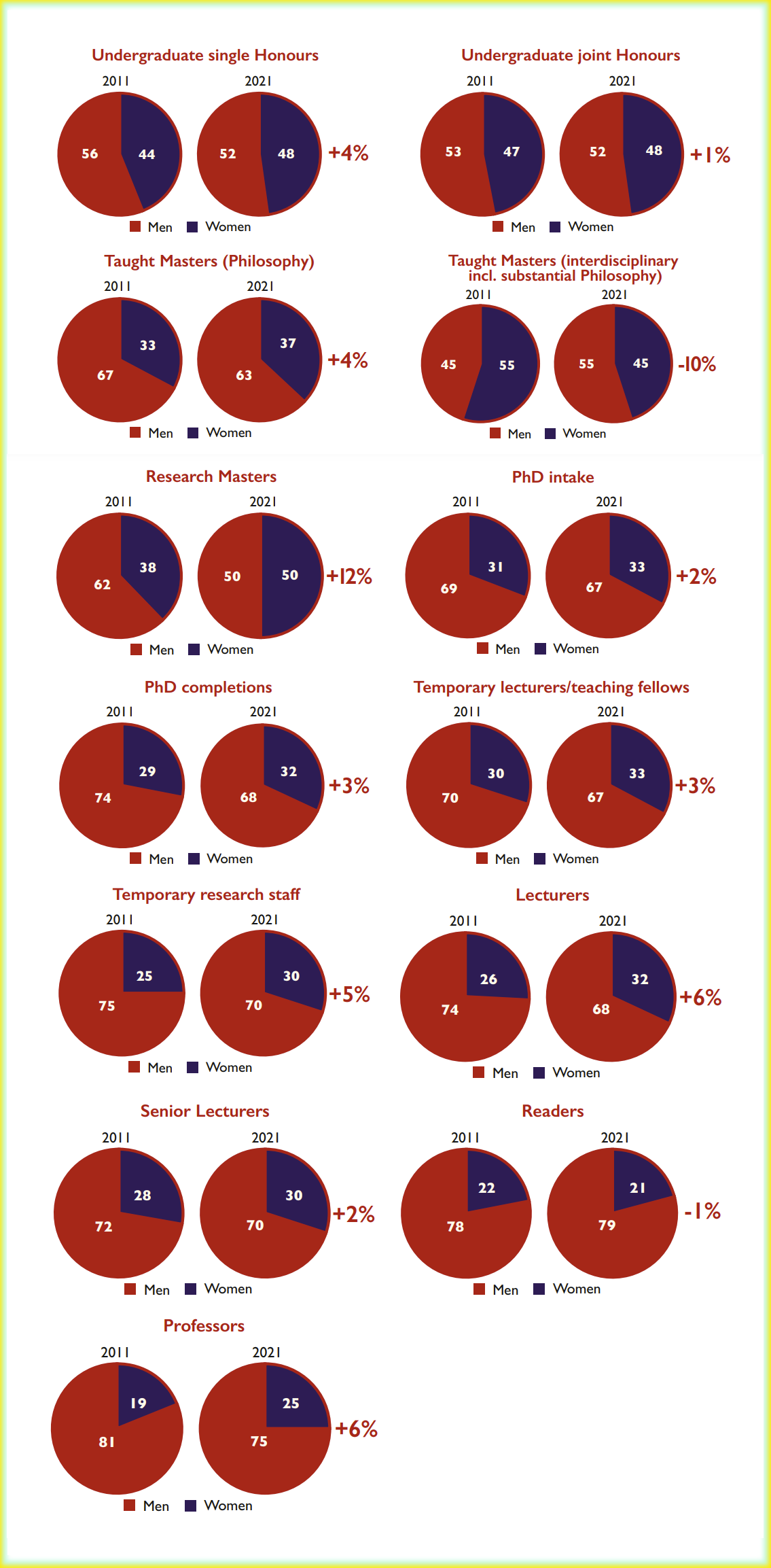

- The new survey results paint a picture of slight improvement in representation of women at nearly all levels, with substantial improvement in the percentage of permanent staff who are women (up from 24% to 30%) and in the percentage of professors who are women, (up from 19% to 25%).

- Nonetheless, there is clearly still much to do: women continue to enrol on philosophy courses in numbers very close to men (48%, up from 44% in 2011), but they continue to leave the field starting at MA level and then yet more at PhD level. The drop-off between undergraduate and PhD remains unchanged at 15 percentage points.

- Overall, the figures suggest it would be well worth focusing attention particularly (though obviously not exclusively) on ways that undergraduate and postgraduate experiences for women can be improved.

-

- empirical studies of undergraduate student enrolments in philosophy degrees

- studies of implicit biases generally, and of their influence on and within philosophy

- work on intersectional oppression in philosophy

-

- sexual harassment in academia

- diversity in the curriculum

- Athena SWAN

- The BPA / SWIP Good Practice Scheme

- The GPS impact report (2018) written as a result of a small-scale survey of departments subscribing to the scheme revealed the two biggest impacts to be culture change—primarily relating to a less hostile and more constructive atmosphere in seminars and workshops—and a higher proportion of female speakers at research events.

-

- parental leave funding for PhD students and early career researchers / temporary contracts

- precarious employment particularly effects women, first generation students, people of colour, disabled people and caregivers

- the gender pay gap isn’t closing very quickly

- the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing gender inequalities

You can read the full report here.

The report posted by the CPA, “Gender Ratio in Philosophy: An Inferential-Statistical Model of Possible Determinants,” takes up the question, “Why are only about one third of academic philosophers women?” Katharina Nieswandt (Concordia), who is leading a team of philosophers and psychologists researching this, writes:

Some of the information is the result of new survey data that reveals what’s different in 2021, compared to 2011:

[Jenny Saville, “Arcadia” (detail)]

The Question: Why are only about one third of academic philosophers women?

Perhaps the most significant change since the 2011 Women in Philosophy report has been the explosion of research attention devoted to the issue of the underrepresentation of women in philosophy. While the underrepresentation of women in academia was already well studied, especially in STEM, in 2011 there had been virtually no empirical research relating to women in philosophy. There has now been a huge amount of work in this area. The 2021 report describes 3 particular topics of research in detail:

Follow-Up Question: Why, then, do women either not enroll in the first place or drop out after the introduction? I.e., why is philosophy not an attractive major to women?

[updated to add:] According to Professor Nieswandt, “this is the first inferential-statistical model, and in fact one of the few studies on the whole topic of women in philosophy to provide any inferential statistics at all.”

The last ten years have seen a flourishing of interventions aimed at improving the situation for women and other marginalised groups in philosophy, including actions related to:

Answer: Mainly because only about one third of students who either enroll in the undergraduate major or stay after introductory classes are women. I.e., at least in North America, the main pipeline leak occurs at the first stage of a potential academic career. Retention within the university system thereafter is probably proportionate, except for a significant drop at the step from associate to full professor…