It is on gravity’s metaphor we lean when we speak of the binding force of love — the attraction that draws ensouled bodies to one another, as if by magic. But for all the progress science has made in the epochs since Newton, along the long procession of history in which the brilliant and the brokenhearted have walked hand in hand, this binding force is still a mystery, still something closer to grace, perhaps the only form of grace that is real.

And when two people have loved each other

see how it is like a

scar between their bodies,

stronger, darker, and proud;

how the black cord makes of them a single fabric

that nothing can tear or mend.

And see how the flesh grows back

across a wound, with a great vehemence,

more strong

than the simple, untested surface before.

There’s a name for it on horses,

when it comes back darker and raised: proud flesh,

We have since discovered three other presently irreducible fundamental forces winding the clockwork of reality, with gravity the weakest of the four, 1038 times weaker than the strongest, and yet the most immediate, the most embodied, the most readily graspable by our creaturely intuitions. The unfathomed thing once explained as magic is now a commonplace of common sense, woven into our elemental understanding of the world and, in consequence, woven into our metaphors — those handles on the door of understanding.

Religions had called it grace. Science, with the young Newton at its helm, called it gravity.

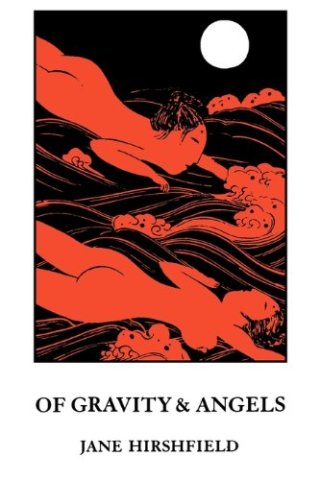

Complement with David Whyte’s sensitive meditation on what we place between ourselves and true love and Derek Walcott’s “Love After Love” — a classic hymn to living ourselves back to life after heartbreak — then revisit Jane Hirshfield’s timeless ode to resilience, “The Weighing.”

FOR WHAT BINDS US

by Jane Hirshfield

as all flesh,

is proud of its wounds, wears them

as honors given out after battle,

small triumphs pinned to the chest —

Centuries after Newton and generations after Carson and Cummings, Jane Hirshfield — another philosopher-poet intimately attuned to the poetics of reality, an ordained Zen Buddhist who thinks deeply and writes splendidly about the living realities and lush metaphors of the natural world — addressed this in a poem that has saved me, and continues to save me, across many seasons of being. Originally published in her 1988 lifeline of a collection Of Gravity & Angels (public library) — a title evocative of the posthumous record of Simone Weil’s exquisite consciousness, Gravity and Grace — it is generously read here for us by the poet herself:

This might always remain so — as the stardust-residue of ideas that was once Carl Sagan reminds us, “the universe will always be much richer than our ability to understand it.” A vast part of me hopes it does remain so — some things are more important felt than known: felt fully and unconditionally, for they can only ever be understood incompletely and conjecturally. Rachel Carson, for all her devotion to the poetics of reality we call science, knew this when she insisted that it is not half so important to know as to feel. E.E. Cummings knew it when, in his impassioned case for the courage to be yourself, he observed that “whenever you think or you believe or you know, you’re a lot of other people: but the moment you feel, you’re nobody-but-yourself… the hardest battle which any human being can fight.”

There are names for what binds us:

strong forces, weak forces.

Look around, you can see them:

the skin that forms in a half-empty cup,

nails rusting into the places they join,

joints dovetailed on their own weight.

The way things stay so solidly

wherever they’ve been set down —

and gravity, scientists say, is weak.

In the autumn of 1664, when the black plague shrouded the world in a deadly pandemic and universities sent their students home for a quarantine the end of which no one could foresee, a young man besotted with mathematics, motion, and light returned to his illiterate mother’s orchard, where he watched an apple fall. A revolution of understanding rose in its shadow — he fathomed the mechanics of a mystery that had enchanted humanity for epochs: how bodies can act on other bodies, attracting one another impalpably and invisibly across space and separation, as if by magic.