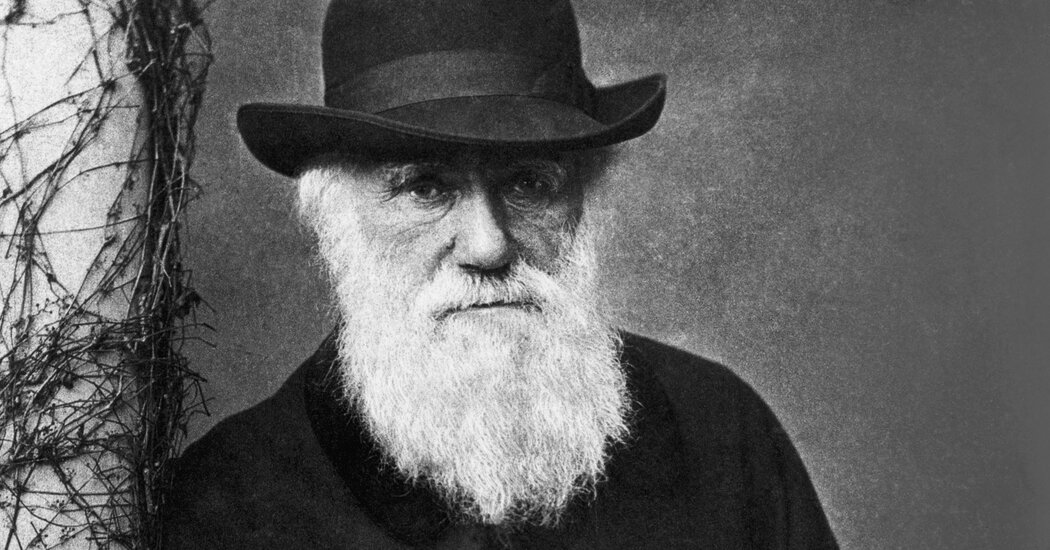

Martineau had an unkind reputation for plainness and lack of feminine polish. “I was astonished to find,” Darwin wrote to his sister Caroline after their first meeting, “how little ugly she is.” They talked “on a most wonderful number of subjects.” Like other men who knew her, Darwin considered Martineau “overwhelmed with her own projects, her own thoughts and own abilities.” Rather than nodding at men’s ideas, she was known for responding with her own.

Lyell found her surrounded by editors and writers for the liberal quarterly Edinburgh Review. She presided over these salons despite deafness that required visitors to all but shout into her ear trumpet. Rebutting the notion that femininity was a handicap, she insisted, in “Society in America,” that only deafness posed a serious obstacle. “I carry a trumpet of remarkable fidelity,” she added, “an instrument, moreover, which seems to exert some winning power, by which I gain more in tête-à-têtes than is given to people who hear general conversation.” At times Martineau smoked cigars. She was a colorful figure welcome at gatherings of artists, intellectuals and politicians.

Her most recent success was “Society in America,” based on two years of travel during which she was feted by artists and legislators. She visited President Andrew Jackson and lodged with the former president James Madison. Both owned slaves, but Martineau did not shrink from portraying the horrors of slavery. She had been writing about it, as both a moral sin and an economically inefficient system, since early in her career. She would have found common ground on this topic with Darwin, a passionate abolitionist who had witnessed slavery’s abuses from Africa to Brazil. His theories about natural selection were motivated in part by a desire to undermine racist notions promulgated by scientists.

Not at all, she replied; a few consecutive hours of hard work tended to exhaust her. Darwin felt the same. He recorded that he felt gratified to learn that Martineau was “not a complete Amazonian.”

Decades later, despite many respectful and admiring interactions with Martineau and other female writers and thinkers, as well as with his intelligent and well-read sisters, wife, cousins and colleagues’ wives, Darwin comprehensively dismissed women’s intellectual potential. “The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes,” he stated in “The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex” (1871), “is shewn by man’s attaining to a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than can woman — whether requiring deep thought, reason or imagination, or merely the use of the senses and hands.”

In 1833, the conservative Fraser’s Magazine had acknowledged the status of Martineau, then 31, by devoting considerable space to arguing with her conclusions and mocking her appearance. Her second published work, “On Female Education,” a defense of her own passion for learning and a critique of the expectation that her education would end when she reached adulthood, came out when she was 20. Her most famous book, “Illustrations of Political Economy,” dramatized human stories featuring the economic theories of Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus and James Mill. Didactic, at times simplistic, it was lucid and accessible and considered a step forward for progressive, human-centered economics.

They compared writing methods. Several of Martineau’s books grew out of her detailed travel journals, which was how Darwin had constructed his own book about his voyage around the world. Martineau was said to require little revision for the many pages that flowed from her pen. Darwin thought her invincible and seems to have expressed this idea.