Time renders most individual moments meaningless, or at least less important than they originally seemed, but it is only through the passage of time that life acquires its meaning. And that meaning itself is constantly in flux; we are always making it up and then revising as we go along, ordering and reordering our understanding of the past in real time.

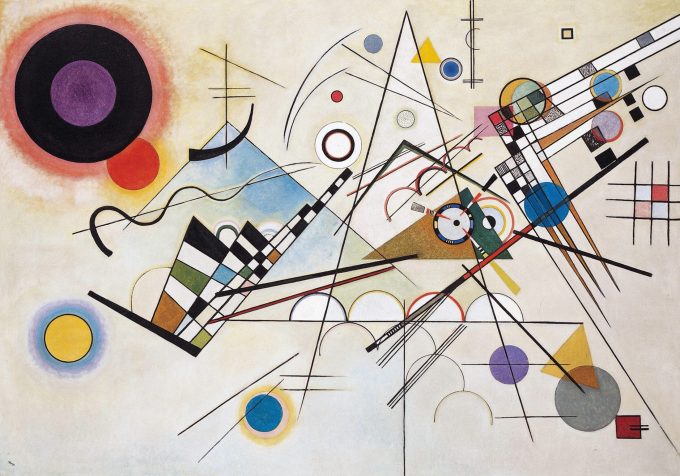

Music — with all the mysterious power by which it “enters one’s ears and dives straight into one’s soul, one’s emotional center” — is made not of notes of sound but of atoms of time. And if music is made of time, and if time is the substance we ourselves are made of, then in some profound sense, we are made of music.

That — the physics and neuroscience of it, the poetry and unremitting wonder of it — is what the science-enchanted classical violinist Natalie Hodges explores in Uncommon Measure: A Journey Through Music, Performance, and the Science of Time (public library). She writes:

In a sentiment consonant with Virginia Woolf’s insight into the strange elasticity of clock-time, she adds:

In her 1942 book Philosophy in a New Key, the trailblazing philosopher Susanne Langer defined music as “a laboratory for feeling and time.” But perhaps it is the opposite, too — music may be the most beautiful experiment conducted in the laboratory of time.

Such patterns, formal and harmonic, relate their components to one another in time. The ear can sense the harmonies to come based on the relative intensities of those that came before, or when thematic material will return by the buildup of a cadence at the end of a development section or variation. It is through this higher sense of rhythm, then, that a simple phrase or a complex form becomes a temporal object: time molded in order to manipulate emotion, putting you through the changes of the present only to bring you back to the past, locating you in a moment that is simultaneously familiar and wholly new.

A century after Virginia Woolf was staggered in her garden into her timelessly stunning insight that “behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern… the whole world is a work of art… there is no Shakespeare… no Beethoven… no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself” — Hodges considers the elemental truth pulsating beneath our experience of music and of our very lives:

Echoing the touching defiance at the heart of Auden’s classic hymn of resistance to entropy, Hodges writes:

Duration is not time — that is something different entirely, something utterly dependent on our perception… The malleability of our perception of time is the stuff of music itself. The concept of passage, the way we generally conceptualize time — seconds elapse into minutes, today becomes tomorrow — is of getting through from one thing to another. In music, time is inseparable from sound itself. A piece of music is a multidimensional entity, a creation molded from time’s clay.

Yet musical time differs from the quotidian passage of ordinary time, even as it exists within that passage. Or, at least, it manifests how susceptible time is to our conscious perception, as much as the other way around.

In a passage that affirms anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson’s wonderfully apt word-choice for how we become who we are — by “composing a life” — Hodges returns to the elemental matter of music:

Music sculpts time. Indeed, it is a structuring of time, as a layered arrangement of audible temporal events. Rhythm is at the heart of that arrangement, on every scale: the cycling and patterning of repeated sound or movement and the “measured flow” that that repetition creates. The most fundamental rhythm is the beat itself, the pulse that occurs at regular intervals and thus dictates the tempo, keeps musical time. In music, a beat is no fixed thing — it can quicken into smaller intervals (accelerando) and stretch out into longer ones (decelerando), depending on the character of a given musical moment and the feeling or fancy of the performer — but it does remain periodic, predictable, inexorable. Even at the level of pitch, which is really the speed of a given sound wave’s oscillation, we are really hearing the rhythmic demarcation of time, a tiny heart whirring at a beat of x cycles per second.

In “the wordless beginning,” spacetime itself was crumpled and compacted into that spitball of everythingness we call the singularity. Even if sound could exist then — it did not, of course, because sound is made of matter — it would have existed all at once. Infinite numbers of every possible note would have been ringing at the same time — the antithesis of music. It is only because this single point of totality was stretched into a line that time was born and, suddenly, there was continuity. Suddenly, one moment became distinguishable from another — the strange gift of entropy, which makes it possible to have melody and rhythm, chords and harmonies.

The music of all cultures, each with its own unique rules to be followed and broken, both weaves and rends the tapestry of audible time. Our experience of musical temporality, like our experience of the day-to-day, consists of patterns of recurrence and, sooner or later, their violation.

With an eye to the basic chord progression, rooted in a tonic, and the satisfying resolution of a rondo, revolving around a circular theme, Hodges writes:

Form, in music, is inherently temporal. It gives some shape to time, or at least designates the pace and manner at which we move through a particular piece. Where do we fare forward or cycle back; which moments expand, and which contract? Likewise, memory — that most universal and yet individual of temporal structures — lends form and shape to experience in biographical time. We inhabit simultaneous, concentric timescales: the time line of the past coiled within the immediacy of the present moment unfolding. Memory creates a metonymic congruence between them, melding past with present in such a way that our former selves move forward with us in time.

Complement Uncommon Measure — in which Hodges goes on to examine through the lens of music such facets of our temporal experience as grief and creativity — with some symphonic reflections on Bach and the mystery of aliveness, then revisit Nick Cave on music, feeling, and transcendence in the age of artificial intelligence and two centuries of beloved writers on the singular power of music.

Implicit in time’s asymmetry, then, is the notion of becoming. The universe unspools itself toward a state of higher entropy; its edges fray, its dust is swept into corners, and this process of degradation and erosion is what separates the future from the past. We think of “becoming” as moving toward something final, evolving into a more perfect and more stable state over time. Yet, by proceeding forward in time, that very process must involve itself in the increasing disorder of the universe. When we seek to become something or someone else, to change our lives and leave the past behind, we necessarily abandon ourselves to entropy: We scatter old pieces of ourselves, willfully smudge our edges and make a mess of things, strive to break free of old symmetries that we feel can no longer contain us. Or, perhaps, that very instinct to change ourselves is a kind of preemptive embrace of the chaos we know is to come, a sign that we have already begun to spin out of control, that time is passing and taking us along with it and that soon nothing will be as it once was.

It’s a strange feeling, beautiful but also eerie: not only that you can step into time’s flow, but that you are the flow itself. I suppose at the heart of that feeling, too, lies the real trouble with time: the terrifying prospect that if time is so subjective, then we are necessarily alone in our unique experience of it. But isn’t it because time lives in us that we can shape it, sculpt it into phrases and cadences and giros and ochos; still it if not stop it, bend it if not vanquish it. And share it.

Yet in every piece of music there are also higher temporal structures at play. Repetition begets pattern, and pattern engenders form, at every scale; thus musical form itself constitutes a macro-rhythm, a pattern of alternations that move the listener through time.

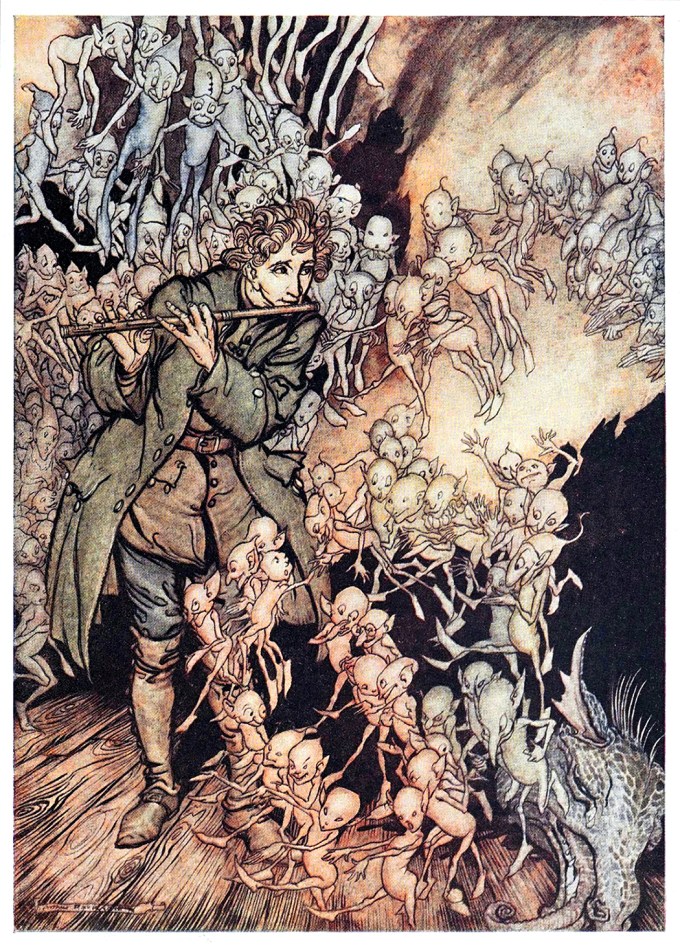

Our minds structure time through the detection of patterns and the predictive anticipation of recurring elements. But although this cognitive function unfolds unconsciously, it is not mechanistic, not robotic, but a vital pulse-beat of our humanity, vibrating with the neural harmonics of emotion, suffused with feeling — for all anticipation is a form of hope and all hope can be shattered or redeemed, taking our hearts along with it. Ever since Pythagoras revolutionized the mathematical structure of music by composing the world’s first algorithm, musicians have been deliberately breaking the buildup of patterns or triumphantly completing them in order to orchestrate an emotional response — the sorrow of unmet hope, the elated relief of its redemption.

[…]

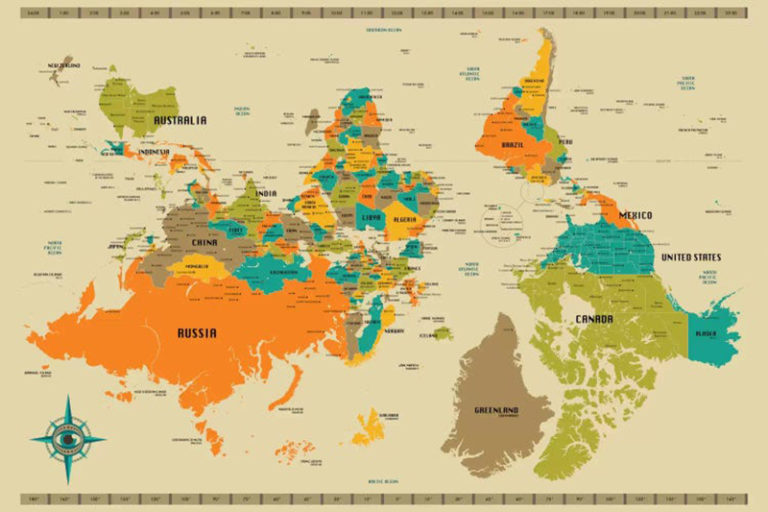

In my native Bulgaria, the tonal tradition rests upon a pattern dramatically different from that of Western music and its twelve-tone scale. (This is why a Bulgarian folk song was encoded among the handful of sounds representing Earth on the Golden Record that sailed aboard the Voyager in humanity’s most poetic reach for making contact with the cosmos.) But while these underlying structures differ across cultures and epochs, music’s reliance on such patterns for its emotional effect is universal. Hodges observes: