There is in this notion an echo of Oscar Wilde’s stirring prison letter, in which he resolved to turn his suffering into transcendence; an echo of Beethoven’s resolve to “take fate by the throat” once he began losing his hearing; an echo of Marina Abramovič, who turned a harrowing childhood into raw material for art.

In Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole (public library), she writes:

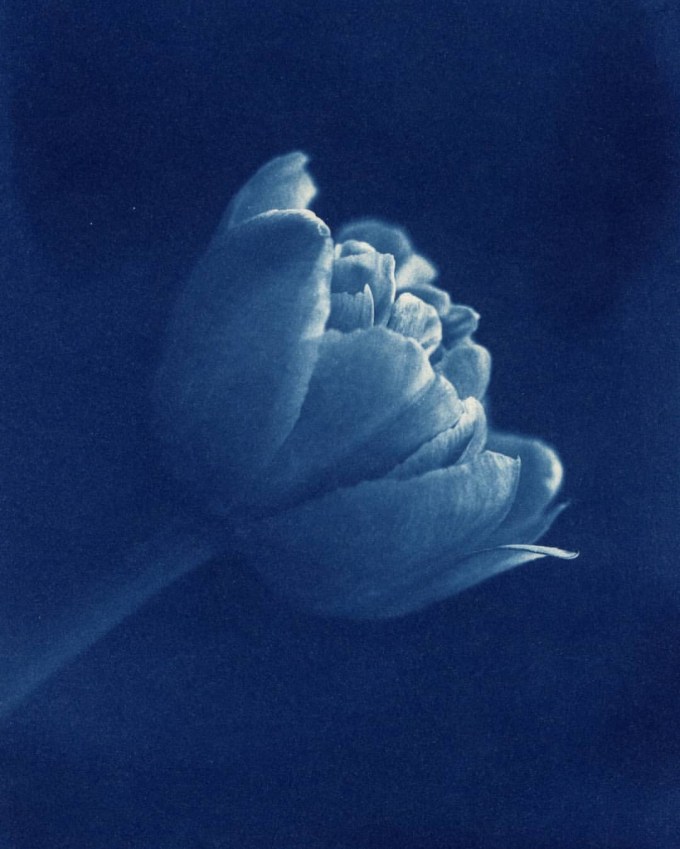

The bittersweet, Cain observes, is most palpable in “those out-of-time moments when you witness something so sublime” — something like, say, a shimmering red leaf twirling in midair without falling — “that it seems to come from a more perfect and beautiful world.” Capturing with extraordinary precision the twin realities between which some of us spend our lives interpolating, she writes:

Bittersweet is a beautiful read in its entirety. Complement it with poet and philosopher David Whyte on the deepest meaning of longing, then revisit Rilke — a classic bittersweet — on the relationship between solitude, longing, and creativity and Nick Cave — the monarch of the modern bittersweet — on hope, cynicism, and the salve for despair.

[…]

In this sense, then, longing becomes not the craving for perfection — for the shimmer of glory, for the myth of closure, for the happily ever after — but a kind of tenderness for imperfection, for the recognition that the place between no more and not yet is the place where the chance-miracle of life lives itself through us, and that is a beautiful place. Cain writes:

When you went to your favorite concert and heard your favorite musician singing the body electric, that was [the bittersweet]; when you met your love and gazed at each other with shining eyes, that was it; when you kissed your five-year-old good night and she turned to you solemnly and said, “Thank you for loving me so much,” that was it: all of them facets of the same jewel. And yes, at eleven p.m. the concert will end, and you’ll have to find your car in a crowded parking lot; and your relationship won’t be perfect because no relationship is; and one day your daughter will fail eleventh grade and announce that she hates you.

That is where Cain’s notion of longing as the litmus test for the bittersweet becomes useful — there is a subtlety in it that sets the spiritual apart from the clinical. Across languages and cultures, across epochs and sensibilities, we have always longed to name our longing. It is encoded in one of Sappho’s most ravishing surviving fragments and bellows from Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” and radiates from everything Nina Simone’s gum stands for. In a passage evocative of Woolf’s “shock-receiving capacity,” Cain writes:

The place you suffer, in other words, is the same place you care profoundly — care enough to act.

C. S. Lewis called it the “inconsolable longing” for we know not what, or Sehnsucht, a German term based on the words das Sehnen (“the yearning”) and sucht (“an obsession or addiction”). Sehnsucht was the animating force of Lewis’s life and career. It was “that unnameable something, desire for which pierces us like a rapier at the smell of bonfire, the sound of wild ducks flying overhead, the title of The Well at the World’s End, the opening lines of ‘Kubla Khan,’ the morning cobwebs in late summer, or the noise of falling waves.” He’d felt it first as a young boy, when his brother brought him a toy garden in the form of an old biscuit tin filled with moss and flowers, and he was overcome by a joyous ache he couldn’t understand, though he would try for the rest of his life to put it into words, to find its source, to seek the company of kindred spirits who’d known the same wondrous “stabs of joy.”

So she gave that flavor of the spirit a name, then set out to understand it by following a procession of researchers who study its kaleidoscopic facets across neurobiology, psychology, social science.

First awakened to it by a curiosity about her own disproportionate love of music in a minor key, Cain realized that “the music was just a gateway to a deeper realm, where you notice that the world is sacred and mysterious, enchanted even” — a realm we can enter through music or a walk in an old-growth forest, through poetry or prayer. She began seeing echoes of this nebulous yet surprisingly common capacity for noticing in the lives of artists and thinkers she admired — Beethoven and Buckminster Fuller, Rumi and Alexander the Great, but none more exemplary than the creative patron saint of her life: Leonard Cohen.

At the heart of it all is an inspired inquiry into “transforming pain into creativity, transcendence, and love,” posed with sensitivity to the realities and varieties of pain we live with, not all of them easily mutable into a poem or a painting or a song.

In a sentiment evocative of Rosanne Cash’s transcendent science-laced reflection on what it means to be an artist, lensed through Adrienne Rich and Marie Curie, Cain adds:

At their worst, bittersweet types despair that the perfect and beautiful world is forever out of reach. But at their best, they try to summon it into being. Bittersweetness is the hidden source of our moon shots, masterpieces, and love stories. It’s because of longing that we play moonlight sonatas and build rockets to Mars. It’s because of longing that Romeo loved Juliet, that Shakespeare wrote their story, that we still perform it centuries later.

I suspect that beneath it all is not an acceptance of but the longing for an acceptance of the elemental interplay between darkness and light, beauty and sorrow, mortality and meaning — the longing we transmute into meaning, that great act of creation.

I too have wondered this while falling in love with the people I live with — Rachel Carson, with her uncommon grasp of the beauty inside the tragedy of transience; Rockwell Kent, who went to the remotest wilderness to discover loneliness as a catalyst of creativity; Beethoven, who turned a lifetime of sorrow into universal joy; Lincoln, who made of his melancholy a source of poetry and power; and Emily Dickinson, who turned the interleaving of love and loss into an eternal garden of delight.

The bittersweet is… an authentic and elevating response to the problem of being alive in a deeply flawed yet stubbornly beautiful world. Most of all, bittersweetness shows us how to respond to pain: by acknowledging it, and attempting to turn it into art, the way the musicians do, or healing, or innovation, or anything else that nourishes the soul. If we don’t transform our sorrows and longings, we can end up inflicting them on others via abuse, domination, neglect. But if we realize that all humans know — or will know — loss and suffering, we can turn toward each other.

It is an act of quiet courage for Cain to reckon with these questions in a culture that so readily cosigns the verdict on matters of complexity with a bellicose X illiterate of nuance. For these are indeed complex, nuanced matters beyond easy binaries, murky even as a spectrum — where do the fertile blues of melancholy end and the deadening black of depression begin? The bittersweet — this enchanted loom of longing on which we weave the tapestry of meaning — exits in the liminal space between the spiritual, the physiological, and the psychological. It is an orientation of the soul laced with neurochemistry and chance.

Longing is momentum in disguise: It’s active, not passive; touched with the creative, the tender, and the divine. We long for something, or someone. We reach for it, move toward it. The word longing derives from the Old English langian, meaning “to grow long,” and the German langen — to reach, to extend. The word yearning is linguistically associated with hunger and thirst, but also desire. In Hebrew, it comes from the same root as the word for passion.

Virginia Woolf called this the “shock-receiving capacity” necessary for being an artist — the willingness to see the totality of life, in all its syncopations of grief and gladness, of beauty and brutality, and feel the shock of it all, and make of that shock something that shimmers with meaning. Susan Cain calls it “the bittersweet” — “a tendency to states of longing, poignancy, and sorrow; an acute awareness of passing time; and a curiously piercing joy at the beauty of the world.” Whitman and Woolf, Carson and Kent, Lincoln and Dickinson were all paragons of the bittersweet.

“Oh, there must be a little bit of air, a little bit of happiness… to let the form be felt.. but let the whole be sombre,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother as he exulted in the beauty of sorrow — not in that wallowing way some have of making an identity of their suffering, not in the way our culture has of fetishizing the tortured genius myth, but in the way of Whitman, who saw the plain equivalence between feeling deeply all of life’s hues and so touching its beauty more deeply, the contact we call art: Those who reach “sunny expanses and sky-reaching heights,” Whitman knew, are also apt “to dwell on the bare spots and darknesses.” He had “a theory that no artist or work of the very first class may be or can be without them”; his own life was living proof of that theory. Two millennia before him, Aristotle too had wondered why an undertone of melancholy seems to reverberate across the personalities of the most fertile minds, the greatest leaders, and the finest artists.

[embedded content]