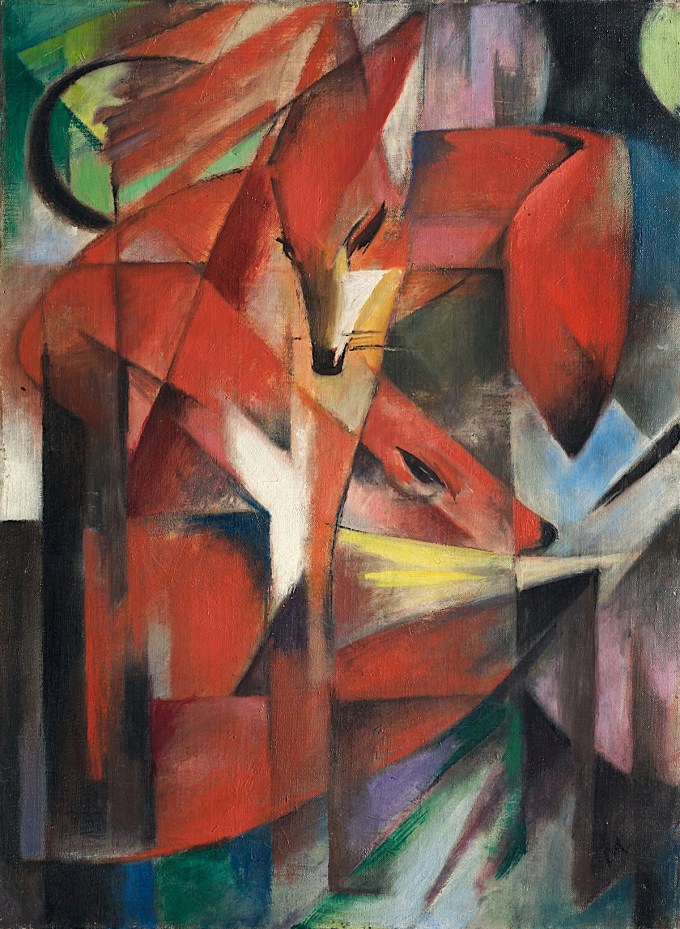

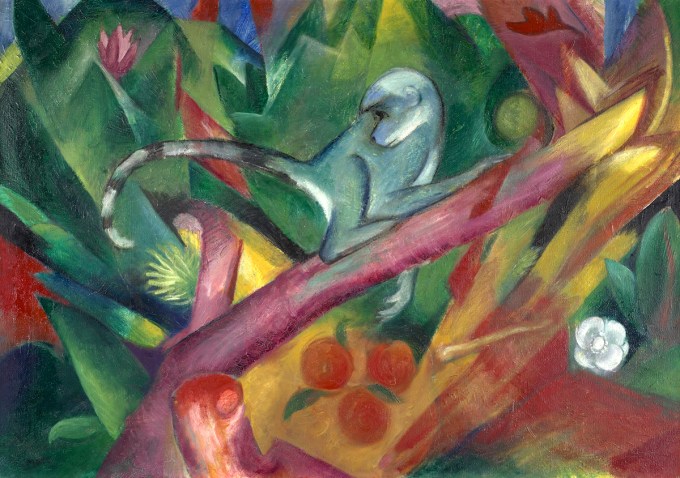

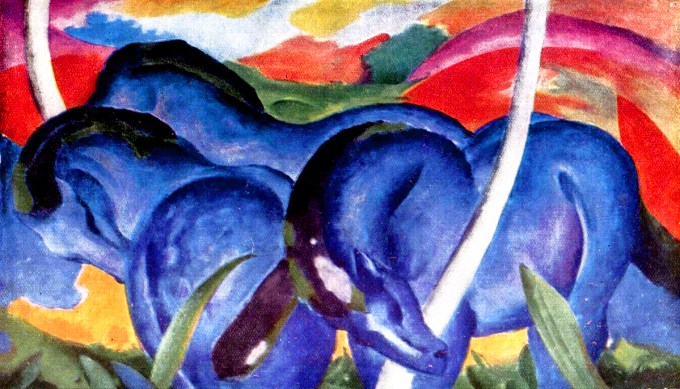

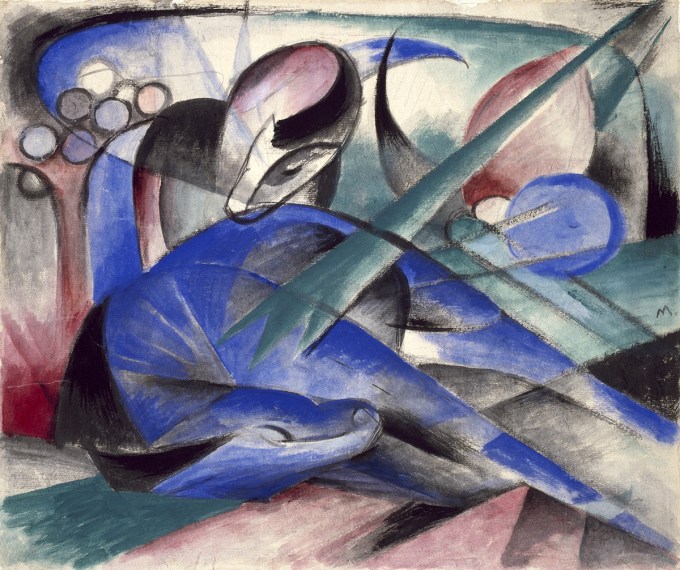

Blue is the male principle, stern and spiritual. Yellow the female principle, gentle, cheerful and sensual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy and always the colour which must be fought and vanquished by the other two!

I do not know how to thank you, Franz Marc.

Maybe our world will grow kinder eventually.

Maybe the desire to make something beautiful

is the piece of God that is inside each of us.

Animals with their virginal sense of life awakened all that was good in me.

Conscripted into the German Imperial Army at the outbreak of the war, midway through his thirties and just after a period of extraordinary creative fecundity, Marc found this improbable outlet for his artistic vitality during his military service. Unlikely to have had any practical advantage over ordinary camouflage, his colossal canvases are almost certain to have served as a psychological lifeline for the young artist drafted into the machinery of death.

Within a month of painting them, Marc was dead — a shell explosion in the first days of the war’s longest battle sent a metal splinter into his skull, killing him instantly while a German government official was compiling a list of prominent artists to be recalled from military service as national treasures, with Marc’s name on it.

In the bleak winter of 1916, in the thickest darkness of World War I, several enormous canvases dappled in pointillist patterns of color appeared across the French countryside, as if Kandinsky or Klee had descended upon the war-torn hills to bandage the brutality with beauty. But no. The painted tarps were military camouflage, designed to conceal artillery from aerial observation — the work of the young German painter, printmaker, and Expressionist pioneer Franz Marc (February 8, 1880–March 4, 1916), who had devoted himself to parting the veil of appearances with art in order to “look for and paint this inner, spiritual side of nature.”

Twenty years after Marc’s death on the battlefields of the First World War, when the forces of terror that had fomented it festered into the Second, the Nazis declared his art “degenerate.” Many of his paintings went missing after WWII, last seen in a 1937 Nazi exhibition of “degenerate” art, alongside several of Klee’s paintings. Marc’s art is believed to have been seized by Nazi leaders for their personal theft-collections. An international search for his painting The Tower of Blue Horses has been underway for decades. In 2012, another of his missing paintings of horses was discovered in the Munich home of the son of one of Hitler’s art dealers, along with more than a thousand other artworks the Nazis denounced as “degenerate” in their deadly ideology but welcomed into their private living rooms as works of transcendent beauty and poetic power.

Animals, Marc felt, were in many ways superior to humans — more honest in their expression of their inner truths, in more direct contact with the inner truths of nature:

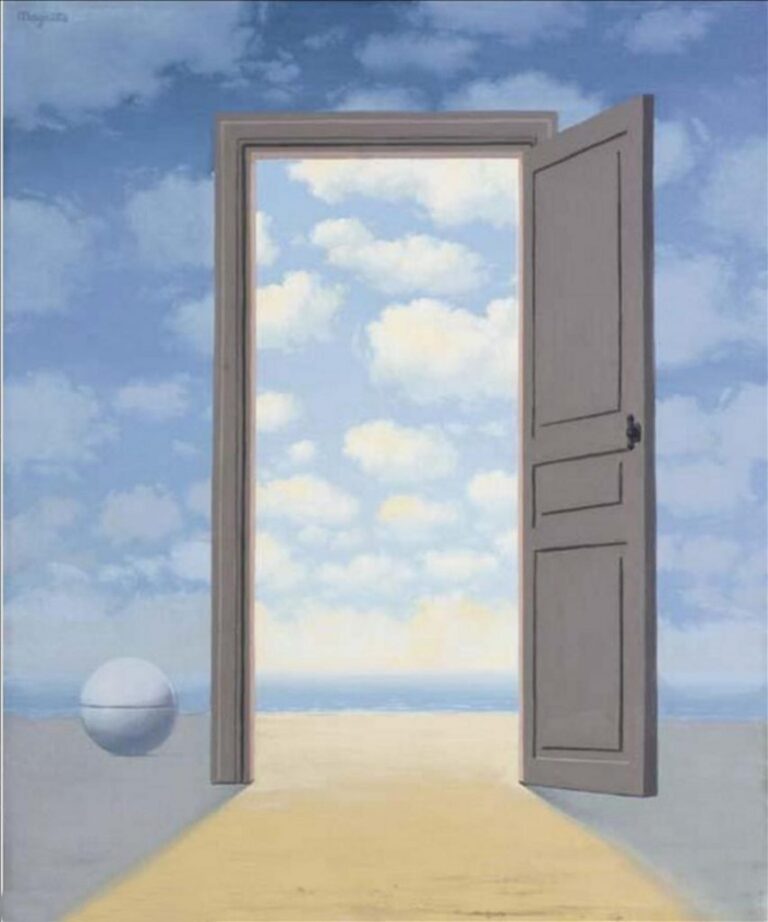

The title poem of Mary Oliver’s Blue Horses embodies the original meaning of empathy, which became popular in the early twentieth century as a term for projecting oneself into a work of art. The poet projects herself into Marc’s painting The Large Blue Horses, running her hand gently one animal’s blue mane, letting another’s nose touch her gently, as she reflects on Marc’s tragic, tremendous life that managed to make such timeless portals into beauty and tenderness in the midst of unspeakable brutality:

In 1910, just before he turned thirty, Marc became a founding member of The Blue Rider — a journal that became an epicenter of the German Expressionist community that included artists like Kandinsky, who had just formalized his thinking on the role of the spiritual in art, and Klee. At the end of that year, Marc began corresponding with the twenty-two-year-old writer and pianist Lisbeth Macke, who was married to one of the Blue Rider artists, about the relationship between color and emotion through the lens of music. Exactly a century after Goethe devised his psychology of color and emotion, Macke and Marc created a kind of synesthetic color wheel of tones, assigning sombre sounds to blue, joyful sounds to yellow, and a brutality of discord to red. Marc went on to ascribe not only emotional but spiritual attributes to the primary colors, writing to Macke:

Among the paintings he produced in those two ecstatically prolific years just before he was drafted was The Fate of the Animals — an arresting depiction of the interplay of beauty and brutality, terror and tenderness, in the chaos of life. An inscription appeared under the canvas in Marc’s hand: “And all being is flaming agony.”

Further exploring the analogy between music and color, Marc envisioned the equivalent of music without tonality in painting — a sensibility where “a so-called dissonance is simply a consonance apart,” producing a harmonic effect in the overall composition, in color as in sound.

Destroyed in a warehouse fire in 1916, The Fate of the Animals was restored by Marc’s close friend Paul Klee, who painstakingly recreated the oil canvas from surviving photographs.