Young, passionate, and poor, they headed for the Rocky Mountains to build a research station for controlled study of how various environmental conditions impact plants, their acclimatization, and their relationships.

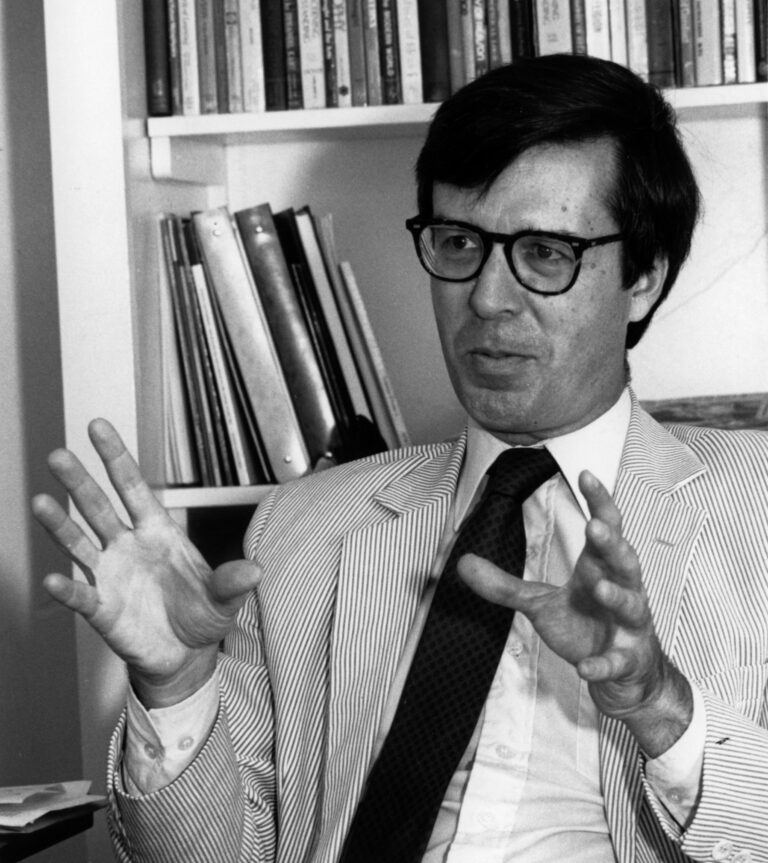

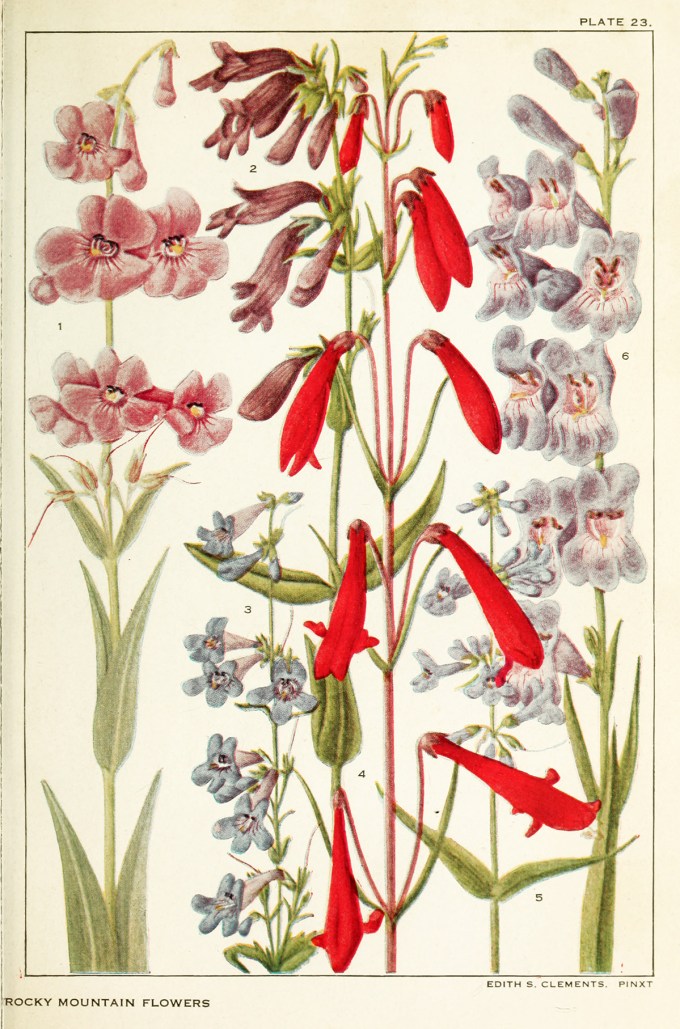

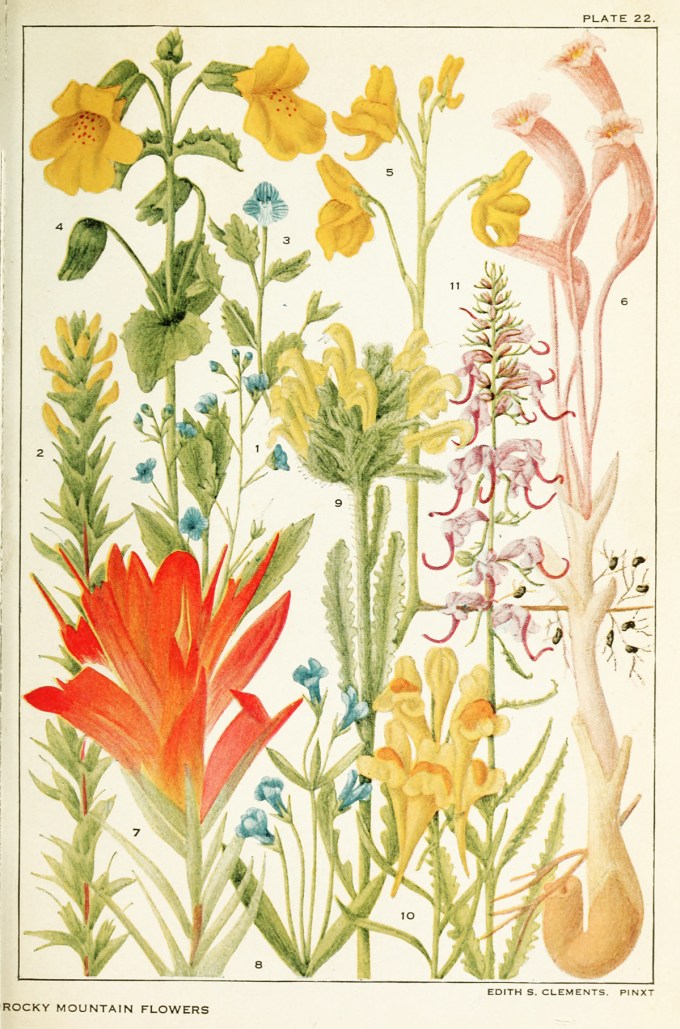

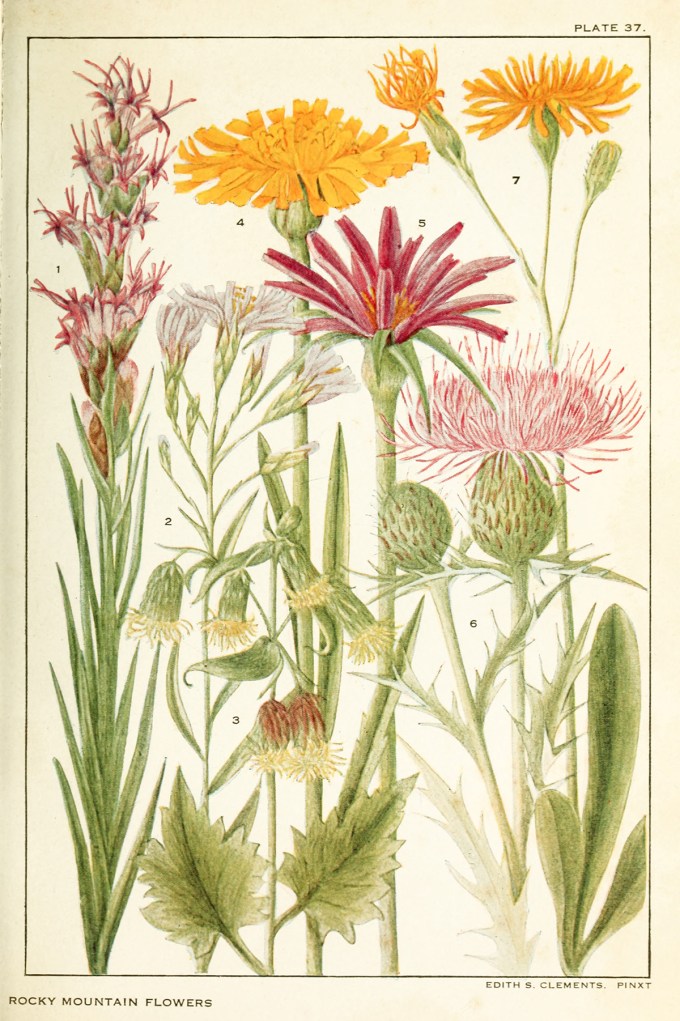

Two centuries after the young self-taught botanist and artist Elizabeth Blackwell painted her astonishing encyclopedia of medicinal plants and as a century after the young Emily Dickinson composed her delicate herbarium of native New England wildflowers, the young Edith Clements began collecting, classifying, photographing, and painting 533 plant specimens from the mountains of Colorado for a meticulously annotated herbarium, completed in 1903 and followed by a second volume in 1904. It became the foundation of the book that would so enchanted Willa Cather a decade later.

Plant ecology entered the popular imagination for the first time, via the portal of Edith’s botanical art.

As they worked, he whistled and she sang.

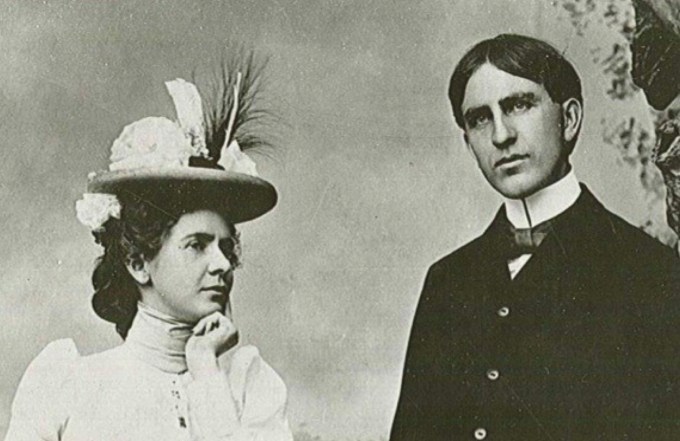

Together with her husband, the influential botanist Frederic Clements, she pioneered the science of plant ecology, lending empirical substantiation to her contemporary John Muir’s poetic observation that “when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” In her 1960 memoir Adventures in Ecology: Half a Million Miles: From Mud to Macadam (public library), penned shortly before Rachel Carson awakened the modern ecological conscience with Silent Spring and half a century before the climate calamity we are now living, Edith Clements prophesied:

In quiet, bold contrast to the era’s appetite for impressionistic and abstract flower blossoms — this was the golden age of Georgia O’Keeffe — Edith painted the whole plant in its natural colors, with the correct number of petals and stamens. She called her paintings “portraits,” reflecting her determination to show people what plants are really like, with all the dazzling scientific complexity undergirding the aesthetic splendor.

There seems little doubt that the application of the principles of ecology to human affairs, whether personal, national or world-wide, would go far in solving the problems that beset us.

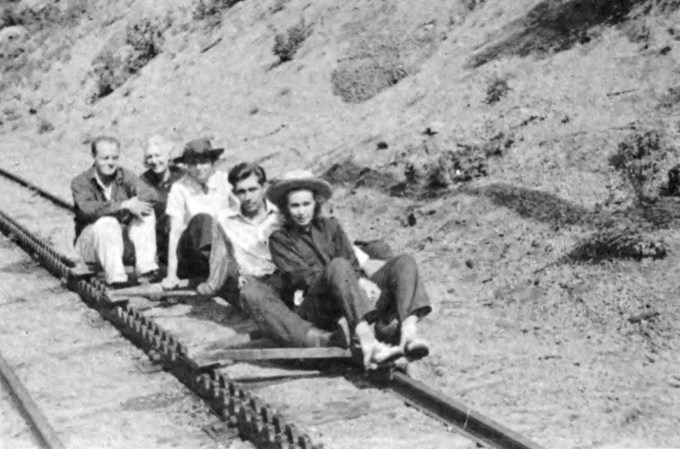

Eventually, the government recognized how invaluable this work would be to the National Parks. Frederic was offered a paid position. Edith was not. They took the assignment anyway, together, and set out to study the reproduction of conifers in forests.

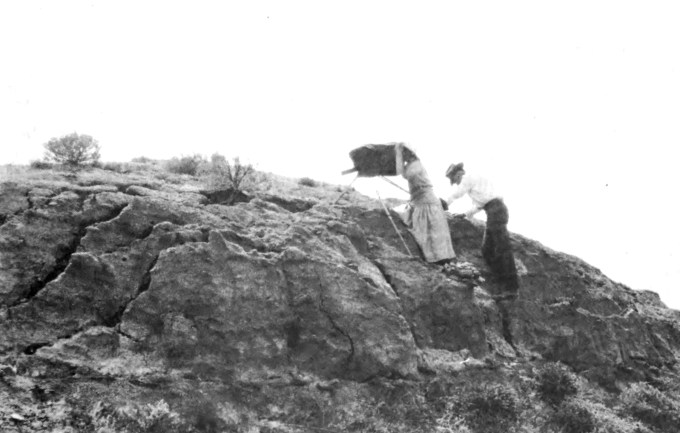

They climbed hills, crossed prairies, trekked into meadows and marshes, Frederic making notes and charts of the vegetation, Edith painting the wildflowers “until swarms of mosquitos made it impossible.”

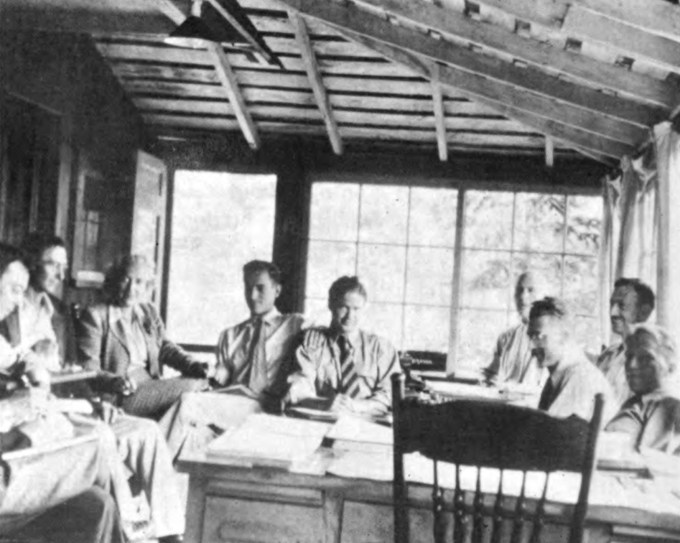

Over the years to follow, the single shack grew to a five-room cottage with a glass-enclosed veranda. Graduate students came to study with Edith and Frederic. Scholars visited from Japan, China, India, Australia, England, and continental Europe.

Nothing like this had been attempted before.

Having begun as Frederic’s doctoral student — the first woman awarded a Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska, then an epicenter of botany and earth science — Edith went on to be his partner in science and life.

In 1926, the editor of National Geographic encountered Edith’s plates of flower family trees, depicting the relationships and evolution of different plant families, and found them to be just the sort of thing to make readers “sit up and take notice.” He was right. When thirty-two of Edith’s paintings backboned a 7,000-word magazine feature about plant ecology in May 1927, the issue sold out in record time. Recognizing the allure of the framable flower illustrations, enterprising young people bought extra copies to resell at manyfold the price.

Edith and Frederic went on to consult the newly founded Bureau of Soil Erosion, helped the Navajo Indian Reservation of New Mexico rewild a dismally overgrazed pasture, opposed the building of dams along the Missouri River, and were called on by numerous panicked government agencies when poor understanding of ecology in agriculture unleashed the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, which devastated the ecosystem of an entire continent, made refugees of thousands of farmers, and inspired Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

The Dream became rugged reality and the shack became the first building of their Alpine Laboratory.

In a stroke of necessity-dictated entrepreneurship, they set out to fund it into reality by coupling their scientific knowledge with Edith’s artistic talent to create an unexampled guide to the wildflowers of the Rockies, which they would then sell to scientific institutions.

With the income from the first herbarium, Edith and Frederic purchased a tiny cabin beneath a colossal pine on the side of a Colorado hill and set up the scientific instruments the university had lent.

“There is one book that I would rather have produced than all my novels,” Willa Cather rued in her most candid interview about creativity. That book was Rocky Mountain Flowers: An Illustrated Guide For Plant-Lovers and Plant-Users (public library | public domain) by the pioneering plant ecologist and botanical artist Edith Clements (1874–1971).

The Clementses devised soil conservation methods for leveling Dust Bowl dunes and replanting them with native grasses and corn crops, mechanisms for diverting and conserving flood water, techniques for rewilding fire-denuded slopes.

As Edith and Frederic Clements pioneered the study of plant ecology together, they were celebrated as “the most illustrious husband-wife team since the Curies.” But their work was also seen as quixotic for its countercultural ethos, decades ahead of its time. In an era of world wars, when science was reduced to military technology and coopted as a handmaiden of dueling nationalisms, Edith and Frederic endeavored to advance the conservation of this one indivisible planet by better understanding the role of climate and the relationships between life-forms. Along the way, they raised and began answering such complex and previously unasked questions as what makes a forest a forest — questions that would unravel some of the most astonishing science of our time.

They called it The Dream.