“It has always pleased me to exalt plants in the scale of organised beings,” Charles Darwin wrote in his autobiography. Long before he developed his theory of evolution, his grandfather — the physician, poet, slave-trade abolitionist, and scientist-predating-the-coining-of-scientist Erasmus Darwin — composed a book-length poem titled The Botanic Garden, using scientifically accurate poetry to enchant the popular imagination with the scandalous new science of sexual reproduction in plants. Published in 1791, the wildly popular book was deemed too explicit for unmarried women to read.

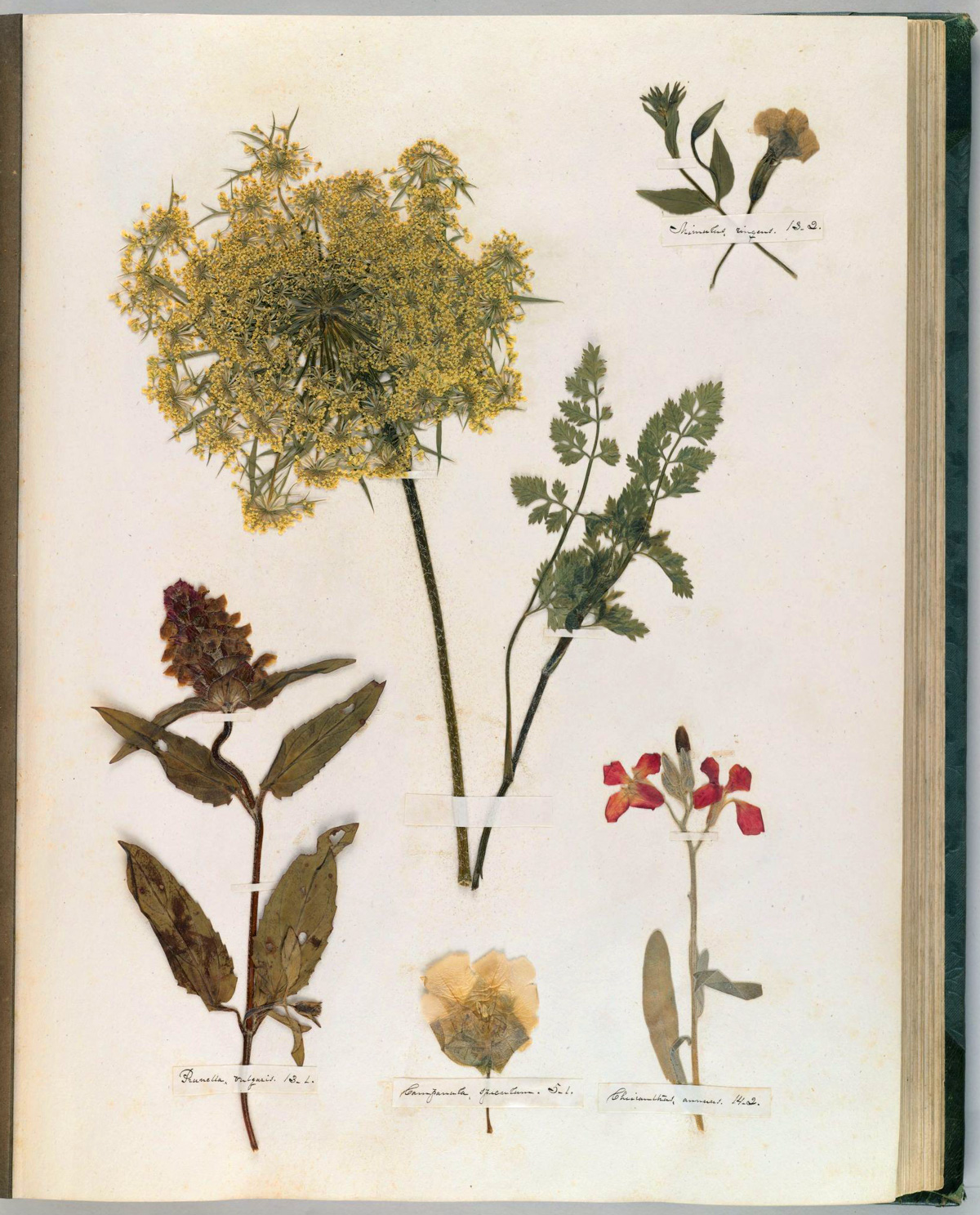

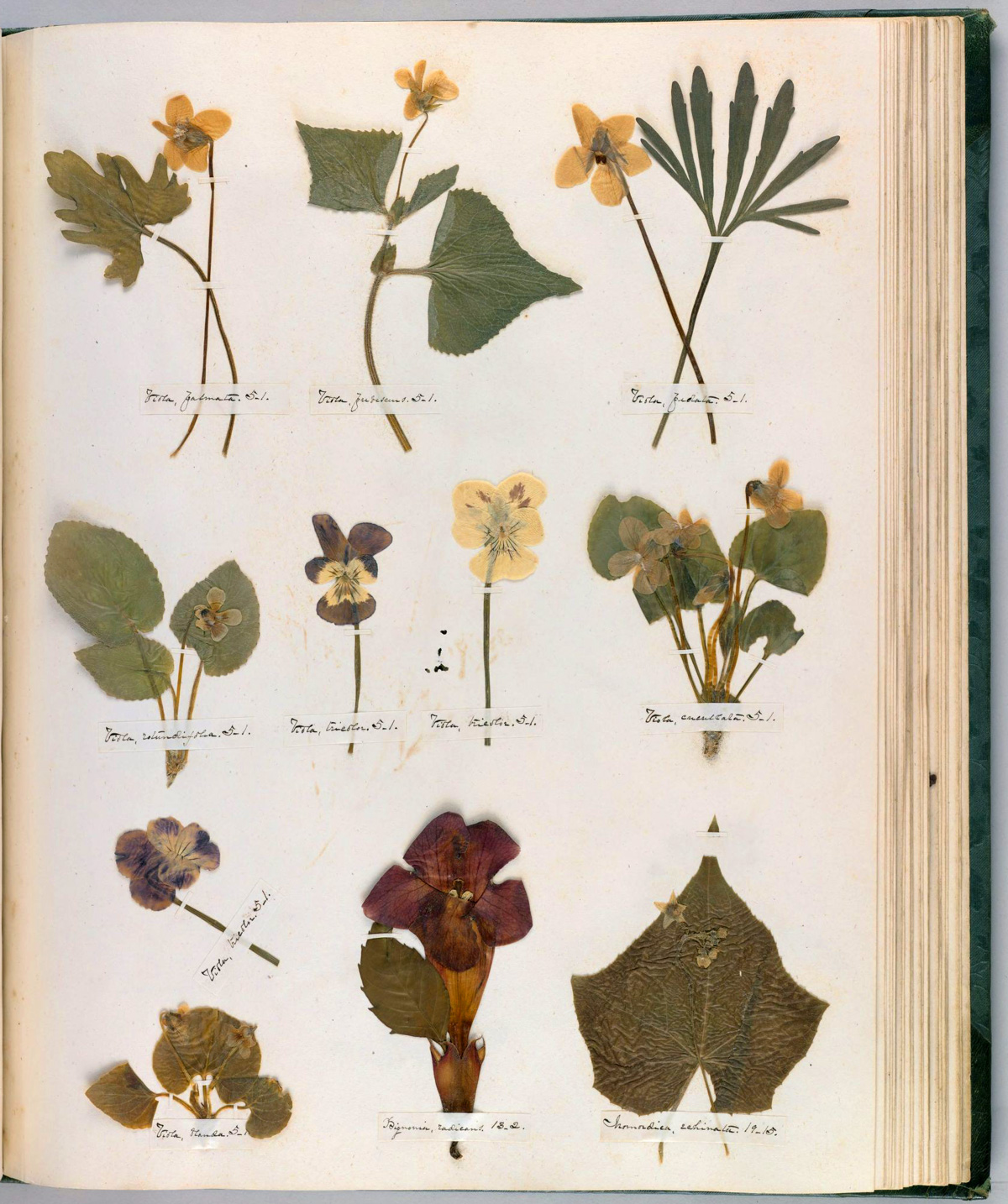

The herbarium was her Emily Dickinson’s first formal work of composition, each flower a stanza in the poetry of landscape and life, deliberately placed to radiate a particular feeling-tone. Her poems were never published in book form in her lifetime, but this book of flowers remained with her and now survives her.

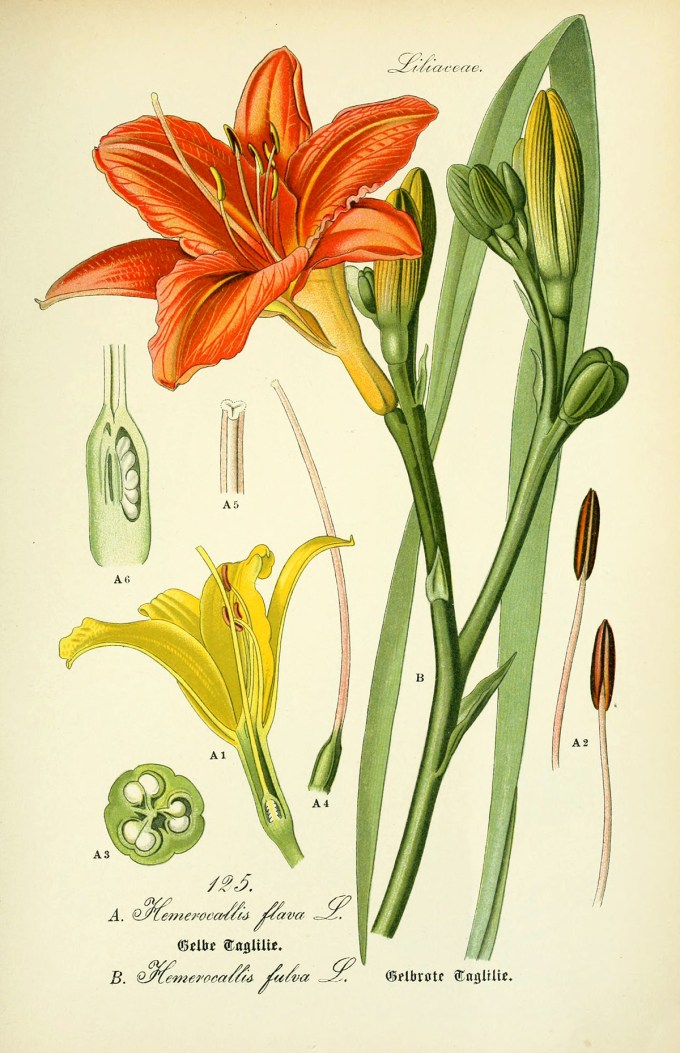

Among the most common perfect flowers are lilies, roses, irises, snapdragons, flax flowers, morning glories, petunias, and the flowers of the coffee plant, the apple tree, and the tomato (which was once known as love apple).

Half a century after The Botanic Garden, the young Emily Dickinson, who was a gardener before she was a poet, approached this dual reverence of the botanical and the poetic from a different angle in her herbarium — a meticulously composed collection of 424 New England wildflowers, including hundreds of perfect flowers, arranged with a stunning sensitivity to scale and visual cadence across the pages of the large album, with slim paper labels punctuating the specimens like enormous dashes inscribed with the names of the plants, sometimes the common and sometimes the Linnaean.

In one sense, perfect flowers are less evolutionarily helpless, not having to rely solely on pollinators to deliver the essential fertilizing material from another plant’s gene pool. But they are also more vulnerable — a single disease can vanquish a species with a self-contained gene pool, while a cross-pollinated plant is more likely to contain genes susceptible to the disease as well as genes resistant to it. Lest we forget, diversity is the wellspring of resilience — in the evolution of nature, as in the ever-evolving conservatory of human nature we call society.

But she had her love and all the perfect flowers.

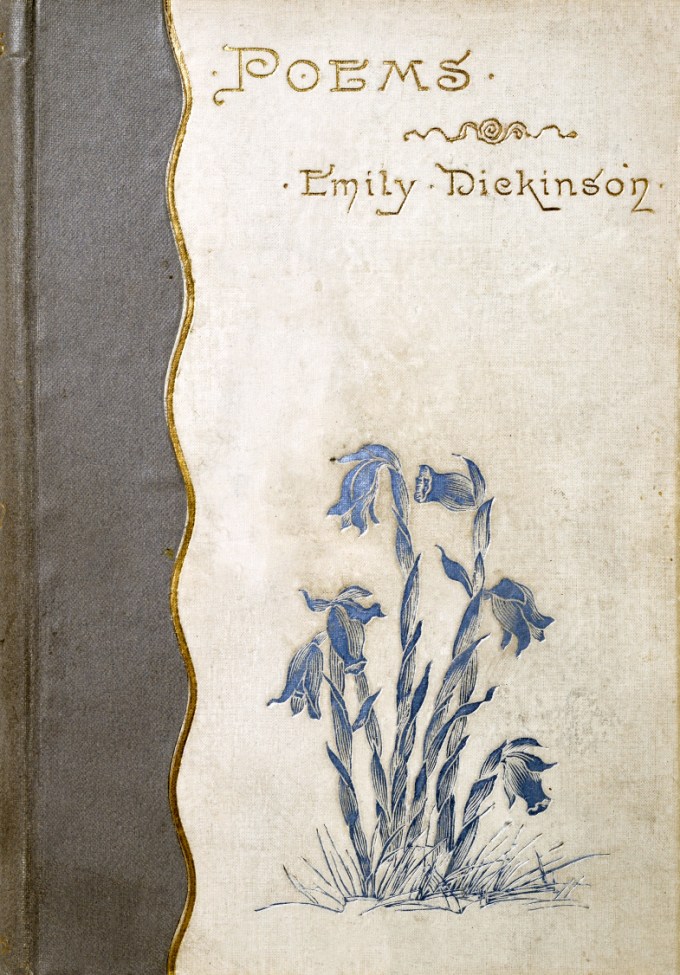

On the cover of the first edition of her posthumously published poetry is a painting of one of her favorite wildflowers — the perfect flower Monotropa uniflora, commonly known as Indian Pipe for its shape when in bloom, or Ghost Flower for its lack of chlorophyll, which she considered “the preferred flower of life.” Once pollinated, the translucent white plant turns dark and dries up before releasing its resilient seeds into the living world.

Amputate my freckled Bosom!

Make me bearded like a Man!

“In each of us two powers preside, one male, one female,” Virginia Woolf wrote in 1929, epochs before we had our ever-expanding twenty-first-century vocabulary of identities, as she celebrated the “androgynous mind” as the mind most “resonant and porous… naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.” Given Woolf arrived at her exquisite epiphany about what it means to be an artist while walking amid her blooming garden, she might have been pleased to know that the botanical term for the blossoms of androgenous plants, also known as bisexual plants — plants that contain both the male pollen-producing stamen and the female ovule-producing pistils, and can therefore self-pollinate — is perfect flowers.

Living when she lived and loving whom she loved, in an imperfect world too small for her genius or her love, Emily Dickinson dreamt of lusher landscapes of possibility, leaping beyond her biology and the limiting binaries of her culture with her bold, subversive verses:

She never lived to see the human world live up to nature’s nonbinary botany of desire.

Plants that contain only one set of gametes — among them begonias, squash, asparagus, and cottonwood — are termed imperfect. Curiously, there are sets of seemingly similar species that fall into opposite categories: the almond tree blooms a perfect flower (which inspired literature’s lushest metaphor for strength of character), while the walnut and the hazelnut do not; soy is perfect, while corn is not.

When Emily Dickinson died at fifty-five, without a single white in her dark auburn hair, Susan — the great love of her life — wrapped her in a white robe and rested alongside her in the small white casket a single pink lady’s slipper — a rare orchid associated with Venus, beautiful and savage, a living Georgia O’Keeffe painting. Into the neck of the white shroud she tucked a small posy of violets — the flower Emily cherished above all others for its “unsuspected” splendor, to which she had dedicated the most dramatic page of her herbarium. “Still in her Eye / The Violets lie,” she had written in one of her earliest and most intense poems dedicated to Sue, which ends with the declamation “Sue — forevermore!”