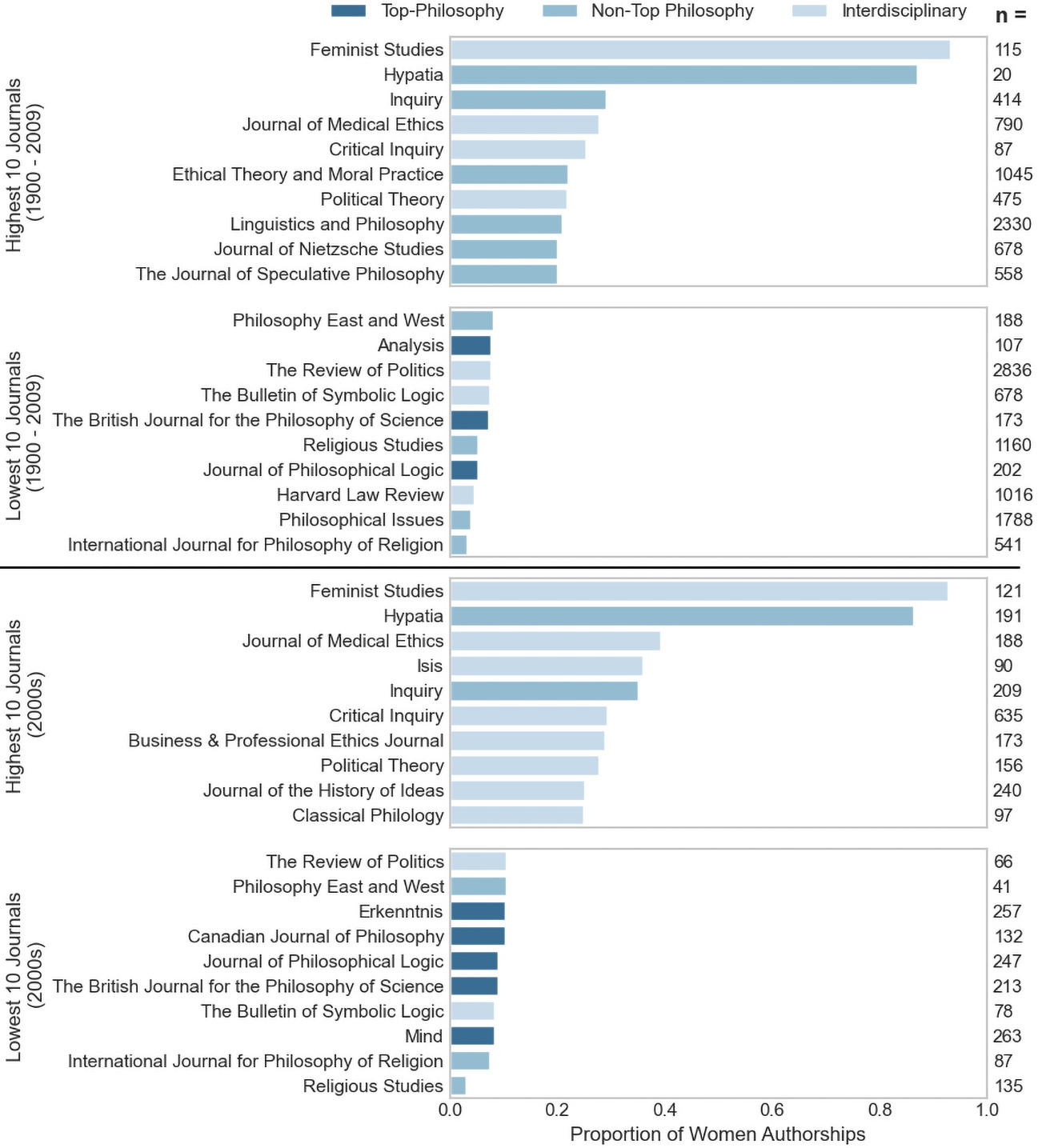

In the following figure, you can see which 10 journals have the highest proportion of articles by women and which have the least, for the periods of 1900-2009 and 2000-2009, color-coded by category:

In conducting their study, the researchers divided up philosophy journals into three categories: “top” (based on an informal survey at Leiter Reports), “non-top”, and “interdisciplinary” philosophy journals. They find:

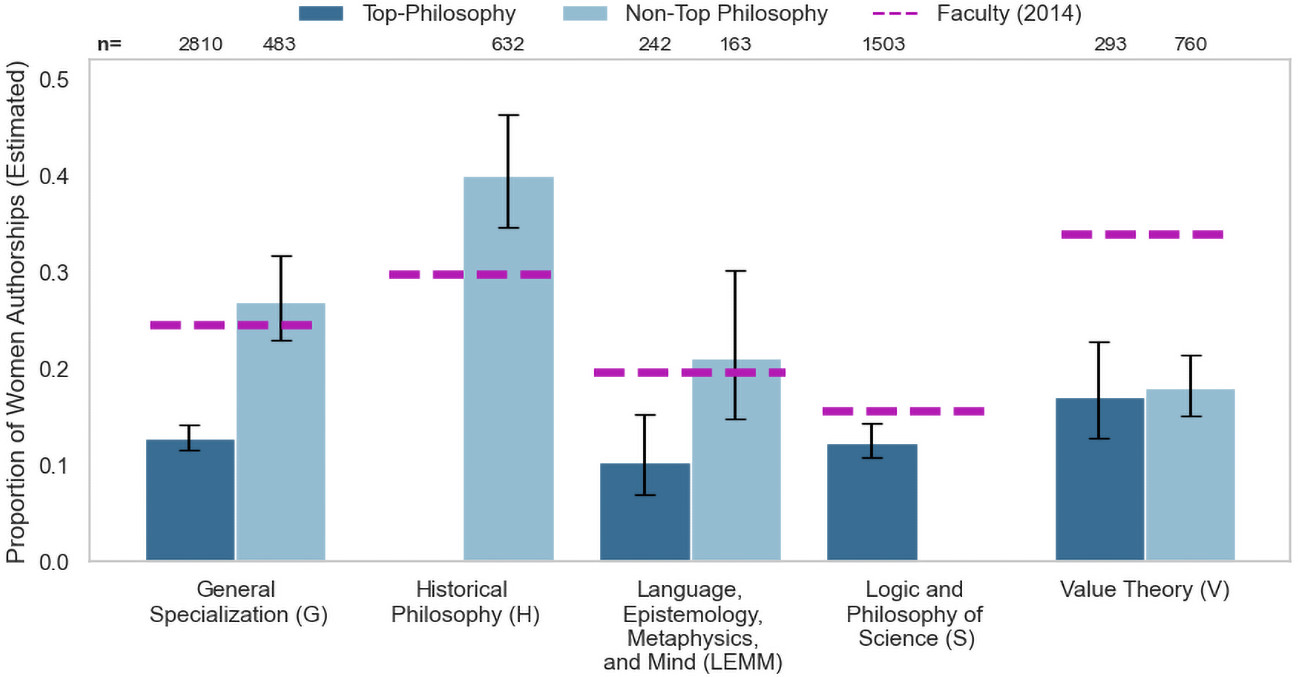

The authors also used a generalized linear model (GLM) to provide estimates of how women’s authorship in philosophy journals varies by area of specialization, and how this compares to the proportion of women working in these areas:

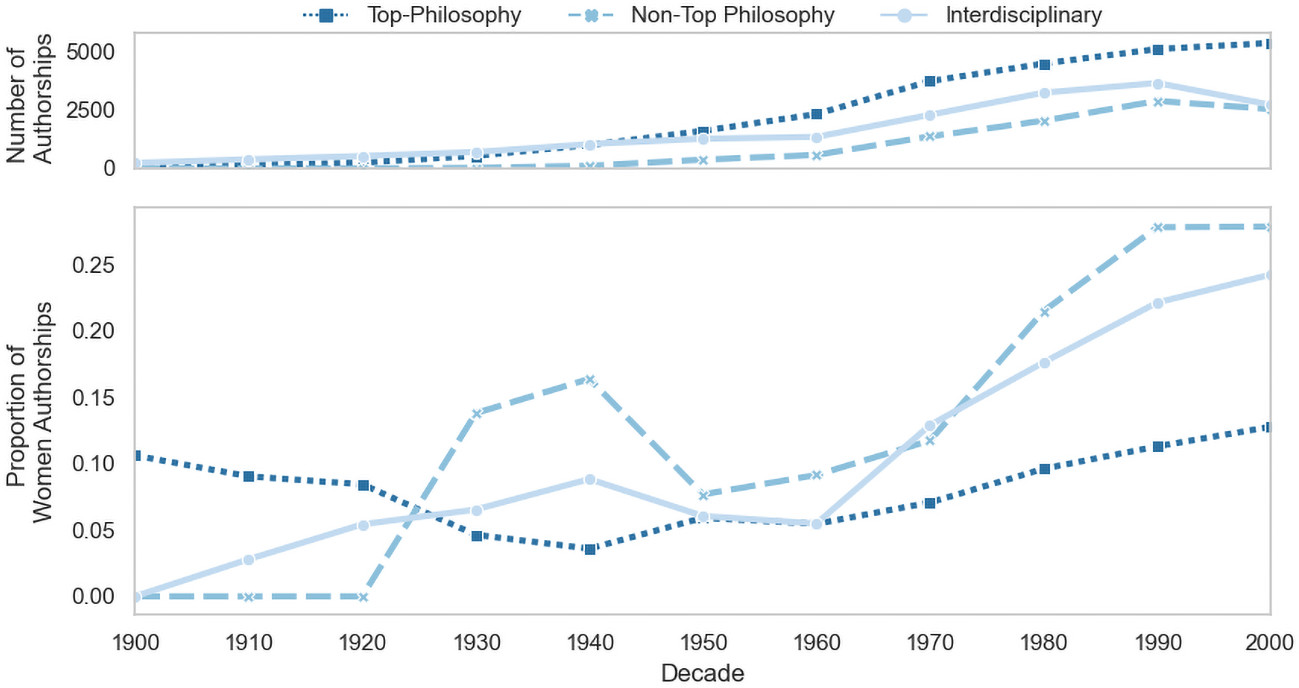

- “an overall increase in the proportions of women authorships in philosophy journals between 1900 and 2009”

- “stagnant growth in the proportions of women authorships for recent decades, especially in Nontop Philosophy journals”

- “the proportion of women authorships has been lowest in Top Philosophy journals over time but that these journals show the greatest increase in the proportion of women authorships between the 1990s and the 2000s”

- “women authors are underrepresented in Top Philosophy journals even compared to the low proportion of women philosophy faculty in the United States overall”

- “the proportions of women authorships in lower-ranked philosophy journals and women philosophy faculty in the United States do not differ”

- “previously reported disparities in Value Theory [between the comparatively low proportion of women authorships and compartatively high proportion of women faculty] are sustained across all philosophy journal categories, including lower-ranked journals where women authors publish in greater proportions”

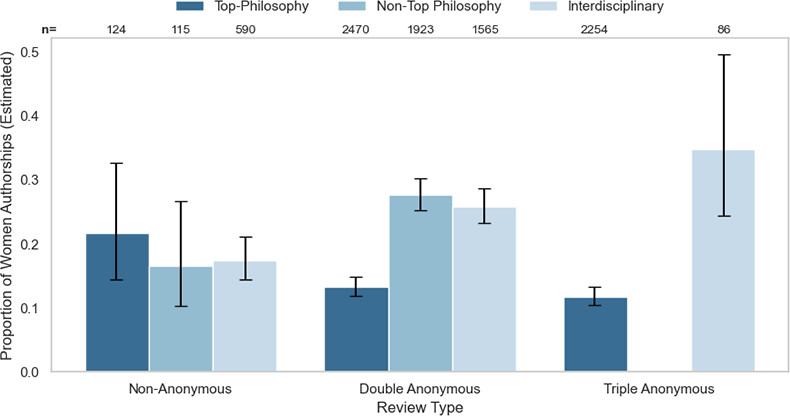

- “Top Philosophy journals practicing Nonanonymous review publish higher proportions of women authors… than Top Philosophy journals practicing Double or Triple Anonymous review… Nontop philosophy journals publish the greatest proportion of women authorships when practicing Double Anonymous review, the most stringent anonymization level within this journal tier… while Interdisciplinary journals publish the greatest proportion of women authorships when practicing Triple Anonymous review”

our new analysis revealed the surprising result that Interdisciplinary journals utilizing Triple Anonymous review and Nontop Philosophy journals utilizing Double Anonymous review publish the greatest proportion of women authors overall. The low proportion of women authorships in journals using Triple Anonymous review in philosophy may have something to do with their being Top Philosophy journals rather than their review process.

(Fig. 11 from Hassoun et al) GLM estimates of the total proportion of women authorships across all journals separated by journal category and review process for the years 2000–2009. Error bars represent the CI based on the output of the GLM (the CIs are very wide owing to the limited data for Nonanonymous review). The number of observations (articles for each journal category and review type in the 2000s) is displayed at the top of the graph with the “n =” label. Again, note that this is the mean proportion estimated by the model on all articles in a journal category.

(Fig. 9 from Hassoun et al). Generalized linear model (GLM) estimates of the proportion of women authorships (2000–2009) by journal AOS compared to faculty AOS (2014). The mean estimated proportion of women authorships across all journals separated by journal category and AOS for the years 2000–2009. Error bars represent the CI based on the output of the GLM. The number of observations (articles for each journal AOS and category in the 2000s) is displayed at the top of the graph with the “n =” label. Note that this figure displays the mean proportion estimated by the model on all articles in a journal category.

The authors discuss their findings and possible explanations for them. For example, regarding the finding that “top” philosophy journals that use triple anonymous review publish a lower proportion of women authors than journals that employ other review types, they say:

(Fig. 4 from Hassoun et al.) Total proportion of women authorships by decade and journal category (1900s–2000s). The top graph shows the total number of authorships by decade and journal category; the bottom graph shows the proportion of women authorships by decade and journal category.

(Fig. 2 from Hassoun et al.) Journals with the ten lowest and those with the ten highest proportion of women authorships for all three journal categories ranked by proportion of women authorships. The top two graphs represent the total proportion of women authorships across all years (1900–2009), and the bottom two graphs represent the proportion of authorships from 2000 to 2009. The total number of authorships per journal “n =” is shown on the right of the graph.

Below you can see the change in number and proportion of women authors in each type of journal from the 1900s to the 2000s:

How much writing by women do philosophy journals publish? How does this vary by quality and type of journal? How does it vary by the type of reviewing manuscripts undergo? How have women’s rates of publication changed over time?

They also used the GLM to provide estimates of how the proportion of women authorships varies by type of manuscript review (non-anonymous, double-anonymous, triple-anonymous):

What, then, explains the low proportion of women authors in top journals? Among the possible explanations offered as hypotheses for further investigation, the authors mention:

- “women are particularly hesitant to submit to those journals”

- “even with full anonymity, markers of gender, including the chosen topic of research, might still be available to referees and editors,” leaving opportunities for gender bias to operate

- “some suggest that men and women may have different views about what counts as valuable contributions to philosophy. So, if the editors and editorial boards for most philosophy journals are primarily men (at around 73 percent in 2010 according to historical data collected from the websites of journals included in this study), they may be more likely to reject work by women philosophers based on the topic, style of the writing, or citation practices”

- “there exists some evidence that academic writing produced by women academics is held to higher standards than that produced by men during the peer review process, even, it seems, when reviewed anonymously”

- “women are… less likely to coauthor than men, and perhaps coauthored articles are more likely to be accepted than single-authored articles”

The study is entitled “The Past 110 Years: Historical Data on the Underrepresentation of Women in Philosophy Journals” (it may be behind a paywall). Readers may also be interested in exploring interactive versions of some of the above data at the Data on Women in Philosophy website.

These are among the questions answered by a new study of women’s publication in philosophy journals, just published in Ethics. The study, by Nicole Hassoun (Binghamton), Sherri Conklin (AviAI Inc.), Michael Nekrasov (Santa Barbara), and Jevin West (Washington).