“Oh! Stars and clouds and winds,” cries the Creature in his anguished wish for self-erasure, “if ye really pity me, crush sensation and memory” — anguish outmatched only by that of his creator. Wishing with every fiber of his being that he could unmake the life he made but knowing that he cannot, Victor Frankenstein goes through his own life as “a miserable wretch, haunted by a curse that shut up every avenue to enjoyment.”

So begins his quest to track down and vanquish the life he ought never to have created in the first place — a quest that ultimately ends in his own destruction.

With an eye to his creation — “the living monument of presumption and rash ignorance which I had let loose upon the world” — Victor Frankenstein laments the responsibility to life, to other lives, that he had sidestepped in the sweep of his passion:

“Once a poem is made available to the public,” the teenage Sylvia Plath would tell her mother a century-some later, “the right of interpretation belongs to the the reader.” Like a great poem, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus would lend itself to infinite interpretations as it came to tower over the popular imagination for centuries to come, casting its long shadow over the fault lines of the future — the future that is now our present, in which so many of the ideas Mary Shelley contoured and condemned are realities both mundane and menacing: artificial intelligence and genetic engineering, racism and income inequality, the longing for love and the lust for power.

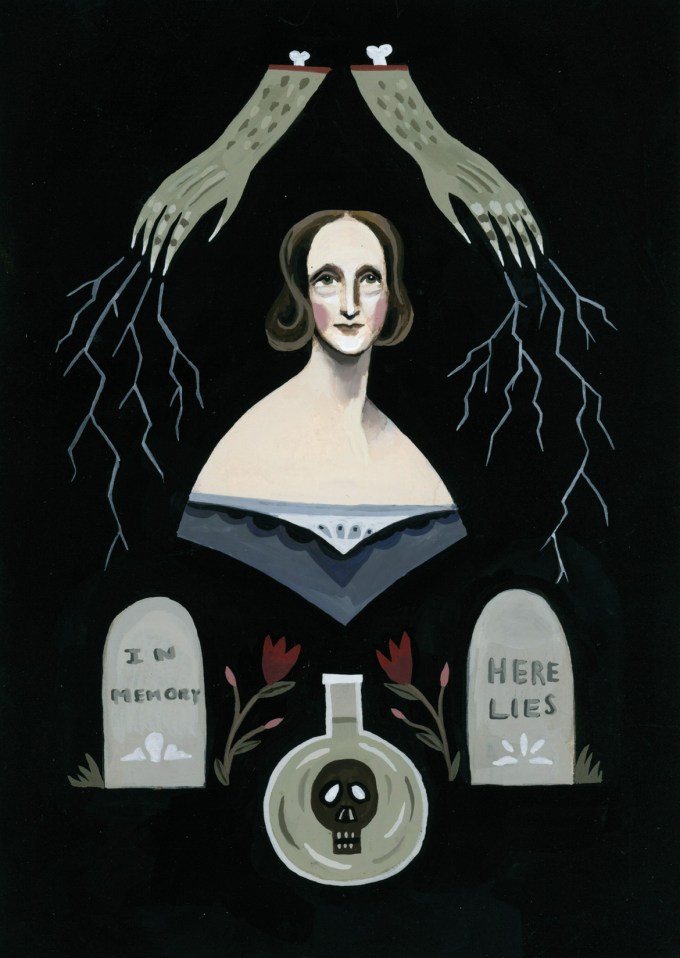

The idea came to her in a “waking dream” several nights later, Mary Shelley (August 30, 1797–February 1, 1851) would recall, looking back on the crucible of creativity — the dream she would sculpt, over the next year of ferocious writing and revision, into one of humanity’s most visionary works of literature.

This was the world Mary was born into, by a mother — the brilliant founding mother of what posterity christened feminism — who had died in giving birth to her. Mary herself — penniless, malnourished, and wearied by long mountain crossings in exile — would barely survive the births of the four children she bore before she was twenty-four, three of whom would die before reaching adolescence. She was eighteen and had already lost her firstborn when she wrote one of the farthest-seeing works of her time, of all time.

There is no record of the exact night or the exact hour. But two centuries later, drawing on Mary’s account of the moment her idea finally arrived as she lay in bed restless with “the moonlight struggling to get through,” astronomers would use the phase of the Moon and its position in the sky over the Villa Diodati to determine that the only light bright enough to clear the hillside and shine through Mary’s shutters in the middle of the night was the gibbous of June 16, just shy of 2 A.M.

A world without the option of abating an ill-conceived life before it has begun is a world that dooms millions to Victor Frankenstein’s fate. What a pause-giving thought: that a girl not yet nineteen, who lived two centuries ago, has a finer moral compass than the Supreme Court of the world’s largest twenty-first-century democracy.

So it is that, late one stormy night, one of them — Lord Byron: gifted, grandiose, violently insecure, “mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” in the words of one of his discarded lovers — pulled a French translation of some German ghost stories from their Airbnb’s bookshelf and read from it to the group. He then suggested that they each write a supernatural story of their own, share the results aloud, and vote a winner.

Of the five, one alone completed the challenge at the Villa Diodati and made of it something to outlast its marble columns. It was not His Lordship.

The notion of reproductive rights was nowhere near the cultural horizon in Mary Shelley’s lifetime. Still beyond the horizon were most basic human rights for women. No woman could vote. No woman could attend university. In her entire century, only four women successfully obtained divorce, and only after demonstrating savage brutality from their husbands. Husbands were legally allowed to beat and rape their wives, who were their property. Women could not own property, including their own bodies.

In June 1816, five young people high on romance and rebellion — two still in their teens, one barely out, none beyond their twenties — found themselves in bored captivity at a rented villa on the shore of Lake Geneva as an unremitting storm raged outside for days. If they couldn’t have the dazzling spring days for which they had fled England, they would have long rambling nights of poetry readings and philosophical disquisitions, animated by wine and laudanum.

Victor Frankenstein creates a life out of vainglorious ambition and existential loneliness, and flees from his own creation in horror. Unable to love the life he has made, he fails to rise to the fundamental responsibility that parenting demands.

In a fit of enthusiastic madness I created a rational creature and was bound towards him to assure, as far as was in my power, his happiness and well-being.

Mary Shelley’s warning rises from the story sonorous and clear as larksong: Life is not to be made, unless it can be tended with love — or else it dooms all involved to a living death.

Rising above the multitude of possible readings is the overarching concern that unites them all: the responsibility of life to itself and the question of what makes a body a person; the clear sense that any life is a responsibility — one not to be taken lightly, not to be sullied with vanity and superstition, not to be used as a plaything of power.