Such experiences appear in or flicker around the edges of every life; we are mysterious to ourselves, and often sense that there are depths we can’t easily sound, or that the origins or destiny of the human reside somewhere in a silence we carry within us.

What accounts for a poem — or for any work of art that reaches from one human consciousness to touch and transform another — is the willingness to stay in that liminal space beyond space, time, and ego, and see what grows there when all the stagnant certitudes we call a self fall away. Doty writes:

But the work is not work in the ordinary sense, not the kind James Baldwin heralded as the artist’s responsibility to their talent when he observed that “beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but most of all, endurance.” (The most that artists of genius can ever offer those of talent is their advice, for they can never offer their genius, true as it is to its Latin roots in the innate and irreplicable spirit of a being.) With an eye to the difference between talent and genius, Doty writes:

[…]

Complement this fragment of Doty’s altogether transcendent What Is the Grass — in which he also explores the paradox of love and death with ravishing soulfulness — with poet, potter, and Black Mountain College icon M.C. Richards on what it really means to be an artist, poet Naomi Shihab Nye on the two driving forces of creativity, and Nick Cave on its combinatorial nature, and then revisit Whitman’s own poetic wisdom on creativity.

Poetry exists to find words for what resists easy naming; we are most often driven to write it or read it when any other sort of language seems incapable of the work required.

Work accounts for a poem of genius about as much as plumbing accounts for the fountains of Rome; it yields a necessary basis, the practical scaffolding that underlies the whole, but cannot in itself engender a sense of transport.

A century after William James observed that “our normal waking consciousness… is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different,” Doty adds:

A century after William James observed that “our normal waking consciousness… is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different,” Doty adds:

It strikes me, too, as the deepest fundament of creativity — this willingness to look for and look at, really look at, the totality of being and to see, as Whitman did, that each of us, every ephemeral living thing, is a “kosmos” containing all “races, eras, dates, generations, the past, the future, dwelling there, like space, inseparable together”; to see this and, as Virginia Woolf did in that rapturous moment when she realized what it means to be an artist, “have a shock”; to make of that shock something that shimmers with the wonder of existence — that transcendent something we call art.

This continues to strike me as a fine way to go through life — perhaps the finest: wonder-smitten by reality, in all its dazzling interleavings.

That dwelling-place of unfinished revelation is both where we find poetry and where poetry leaves us:

[…]

It’s the same thing poetry does, opening within the ordinary a space where time pools or stills, and something blazes up out of the familiar.

Visions are not as far from ordinary life as we sometimes think, and artists need to live as if revelation is never finished.

Drawing on the work of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin — who too contained multitudes as a Darwinian Jesuit priest, paleontologist, and physicist reckoning with the same permeable boundary between knowledge and mystery that Whitman channeled in his poetry — Doty adds:

This elemental truth is what Emily Dickinson contoured in her proto-ecological poem about the coextensive wonder of a single flower and what prompted the Nobel-winning quantum pioneer Erwin Schrödinger to make his seemingly cryptic but exquisitely reasoned statement that, in the whole of the universe, “the over-all number of minds is just one.”

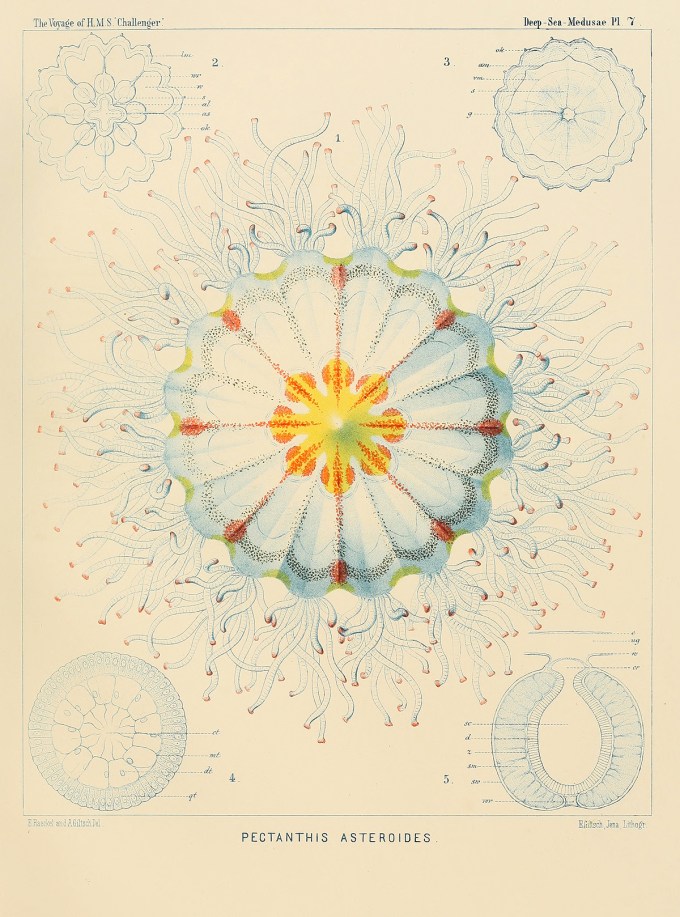

The world enters us and departs, just as language and image and idea are imprinted upon our consciousness, considered, forgotten, passed on, released. I make this book out of thinking, feeling, experience, light on my computer screen; as I write the light from the screen enters my body through my eyes, the impulses of my brain move my fingers to push against these keys (a little too firmly, I am told, from my years of working on typewriters). There is no place in the world where that which is “I” firmly, clearly ends, no line of demarcation. The body of a jellyfish is somewhere between 94 and 98 percent water, which means that a body of water is moving in the water. A jellyfish lacks much in the way of separation from its milieu, and might reasonably be said to be something more like a process the water is performing, an activity taking place in water, than a separate being.