The foregoing excerpts are from a post by Professor Robeyns at Crooked Timber. In it she solilcits suggestions, and calls for a geographic equivalent to the Gendered Conference Campaign, which publicized events, edited collections, etc., that lacked women as a way of drawing attention to systemic patterns of exclusion in philosophy. She also recommends that we:

Further discussion and suggestions welcome.

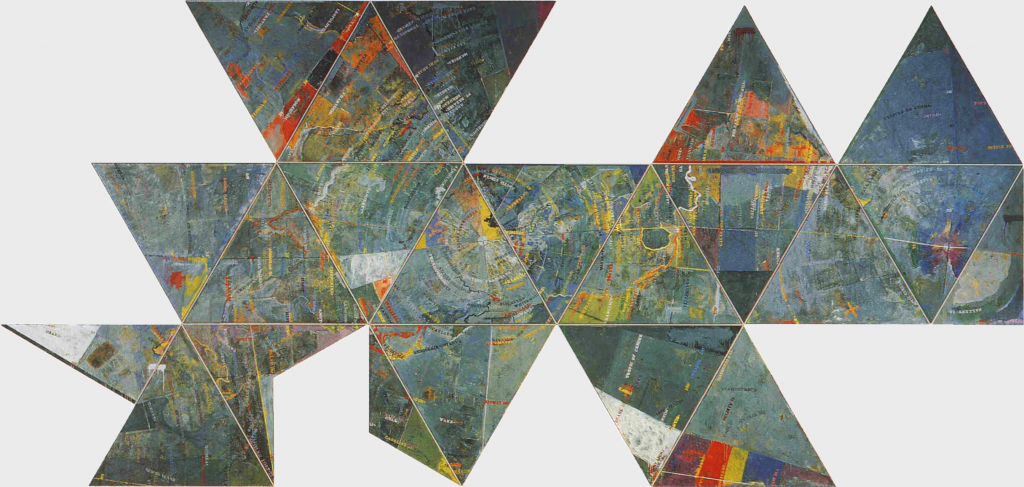

Jasper Johns, “Map (Based on Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Airocean World)”

On Tuesday, I discovered that the Oxford Handbook of Political Philosophy has 23 chapters (the introduction included), of which 20 have been written by political philosophers based in the USA, 2 by political philosophers then based in the UK who have in the meantime moved to the USA, and 1 chapter by a duo of political philosophers based in Oxford. And while this is a pretty striking case, in many if not most handbooks authors from the USA and the UK are numerically dominating.

It’s a self-reinforcing phenomenon—“a vicious cycle of ignorance and exclusion”—that produces a rather limited view of philosophy:

One thing to note is that, owing to today’s communications technology (among other things), philosophers around the world are better equipped to overcome geographic and linguistic constraints than ever before. Yes, such connectedness can facilitate and perpetuate patterns of inequality and domination, but may also provide the means for interactions which could upset those patterns. The “UP Directory” is one example of this, but so, too, are the many online events now taking place—not just conferences and summer schools, but forms of cooperation such as the Virtual Dissertation Writing Groups.

Most of the time, editors of such overview books are based in the USA or the UK; most of the time, they get asked for those roles. They face many barriers in knowing what political philosophers do who are from/based in countries outside the Anglophone academic centre—the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The philosophers that are not based in that academic centre are less often published in the journals that those editors read. They are less likely to (be able to) attend the conferences that those editors attend. They are less likely to be among the seminar speakers. And, as we can infer from the above pretty striking example, they are less likely to be invited to contribute to standard works in their field.

The geographic exclusiveness of this volume is hardly unique. As she notes, it manifests itself in other, related professional ways:

Related: “Analytic Philosophy, Inclusiveness, and the English Language“, “Levelling the Linguistic Playing Field within Academic Philosophy“, “Dominance Of The English Language In Contemporary Philosophy: A Look At Journals“, “Language, Philosophy, and the Allure of Ignorance“, “Virtual Dissertation Writing Groups“, “Open, Live, Online Philosophy Events”

Ingrid Robeyns, professor of philosophy at Utrecht University, recently came across something that captured extraordinarily well a problem she had long been aware of, and was prompted to write about it:

Edited volumes, conferences, seminar series with only speakers from the academic centre of philosophy transport an image: that ‘good’ philosophy is done in the USA and other Anglophone countries, and that if one wants to be successful, that’s where you have to be. This image, however, narrows and impoverishes philosophy, as it excludes valuable knowledge produced elsewhere.

She also suggests, in a comment, making use of the “UP Directory,” a listing of philosophers from underrepresented groups in philosophy, including those not citizens of an anglophone country, now hosted by the American Philosophical Association.

read (more often) the works of those who are not working at universities in Anglophone countries. Read their papers and books. Make sure your library has a subscription, e.g. to the South African Journal of Philosophy. Invite political philosophers from outside the academic global centre to give talks at your department. Invite them to be visitors. Attend their conferences (which is now often even possible without travelling). If you’re involved in running a journal, try to free up fonds to help papers originally published in languages other than English to be translated.