Perhaps dreams are an arena that can enable supracognitive powers to perform calculations and perceptions of reality that may be incomprehensible in our wake state. In my case, my paradox was making an equivalence between incomprehensible equations presented by the bearded man and his counterclockwise whirling hands. This counterclockwise motion turned out to summarize the mathematics that was obscuring the underlying physics to be unveiled.

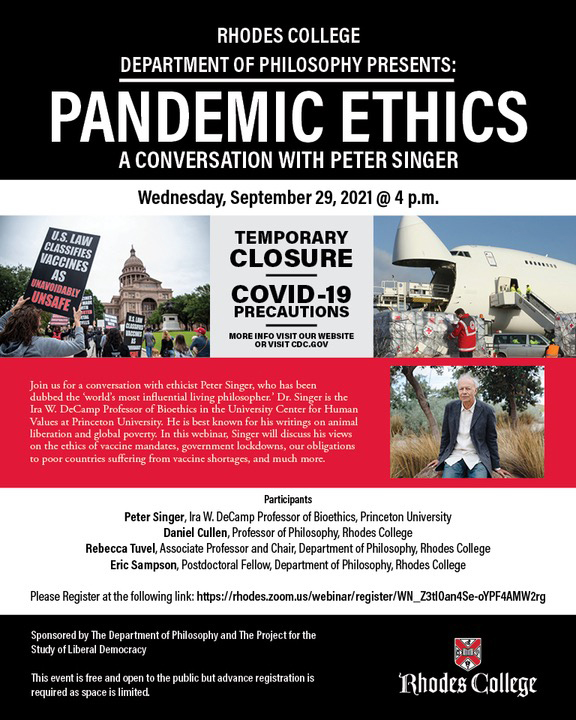

Clarifying the theory’s central premise of a “nonlocal conscious observer” — which, to be clear, is not a science-cloaked euphemism for “God,” as much as certain spiritual factions have attempted to appropriate quantum science for their ideological purposes in the century since its dawn — Alexander writes:

When Isham asked the young American physicist why he was at Imperial College, Alexander flinched with the tenderly human fear that he was about to be called out for being a fraud. But he answered with a scientist’s clarity and a Stoic’s composure: “I want to be a good physicist.”

Epochs ahead of their time, Schrödinger’s propositions not only shaped the course of physics but inspired the research that led to the discovery of the structure and function of DNA, which made tangible the ambiguous and amorphous idea of the genetic unit of inheritance that had been rippling across the collective mind of science. Alexander writes:

Sometimes to get around a scientific problem, one must consider possibilities that defy the rules of the game. If you don’t enable your mind to freely create sometimes strange and uncomfortable new ideas, no matter how absurd they seem, no matter how others view your arguments or punish you for making them, you may miss the solution to the problem. Of course, to do this successfully, it is important to have the necessary technical tools to turn the strange idea into a determinate theory.

Planted into other fertile and unorthodox minds, these ideas went on to seed the founding principles of information theory (in Claude Shannon’s mind) and cybernetics (in Norbert Weiner’s mind), shaping the modern world — the world in which I am extracting these thoughts from my atomic mind, externalizing them by pressing some keys over a circuitboard, and transmitting them to you via bits that you receive on a digital screen to metabolize with your own atomic mind. Here we are, thinking together, threaded together across the globe by fiber optic cables and relativity. All the world is mind, woven of matter.

[…]

Woolf would come to write that “our minds are all threaded together… & all the world is mind.” Schrödinger would come to compose the part-koan, part-aphorism, part Wittgensteinian declarative statement that “the total number of minds in the universe is one.”

Woolf would come to write that “our minds are all threaded together… & all the world is mind.” Schrödinger would come to compose the part-koan, part-aphorism, part Wittgensteinian declarative statement that “the total number of minds in the universe is one.”

Reflecting on Einstein’s epoch-making reckonings with the unseen nature of reality, which began in little Albert’s childhood encounter with the compass that gave him the intuitive sense that “something deeply hidden had to be behind things,” Alexander writes:

Let us assume that consciousness, like charge and quantum spin, is fundamental and exists in all matter to varying degrees of complexity. Therefore consciousness is a universal quantum property that resides in all the basic fields of nature — a cosmic glue that connects all fields as a perceiving network.