In many ways, of course – philosophers are just people, after all; philosophy students are just students; and philosophy departments are just academic departments – you’d expect the obstacles to gender equality in philosophy to be pretty much the same as those facing wider society in general and universities in particular. Doubtless that’s true to an extent. For example, there’s no reason to think that sexual harassment is any more of a problem in philosophy than it is in any other male-dominated discipline; hence institution-wide approaches, if they work in general, ought to work in philosophy in particular. But even where a problem isn’t distinctively a problem for philosophy, it doesn’t follow that we can just leave the problem to Them Upstairs to sort out.

How have things changed for women in philosophy over the past decade?

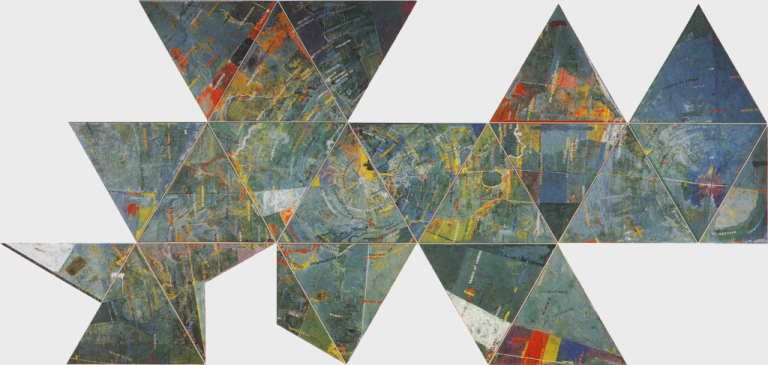

The occasion for Professor Beebee’s refelections was the 10-year anniversary of the publication of a report she and Jenny Saul (Sheffield) wrote for the Society for Women in Philosophy (UK) and the British Philosophical Association entitled “Women in Philosophy in the UK“. The report looked at the number of women in philosophy in the UK at various levels. The two of them recently conducted the survey again. Here are the results, then and now:

Here are some of the positive developments she notes:

- It has become more widely known that women are underrepresented in philosophy.

- It has become more widely acknowledged that women’s underrepresentation in philosophy is a problem.

- There has been increased empirical research on women’s underrepresentation in philosophy at various levels (from becoming a philosophy major to article citation rates).

- There is active discussion over how to improve the representation of women in philosophy and their experiences in philosophy.

- Feminist philosophy has become mainstream.

- Women in the history of philosophy are getting more attention.

- The sexist and racist views of well-known philosophers are no longer automatically being ignored or downplayed.

- Philosophy seminars are less “incredibly aggressive”.

- There is better representation of women on syllabus reading lists.

- There is better representation of women as conference speakers.

- Childcare is more frequently offered at conferences.

I’d like to invite women in philosophy—students, faculty, and staff—to share their thoughts about Professor Beebee’s observations, and more generally about being a woman in philosophy, what has changed over the past decade or so, remaining issues and problems, possible strategies and solutions, and so on.

| % of the below categories who are women (UK) | 2011 | 2021 |

| Philosophy Undergraduates | 44% | 48% |

| Philosophy Master’s Students | 33% | 37% |

| Philosophy PhD Students | 31% | 33% |

| Philosophy Lecturers | 26% | 32% |

| Philosophy Professors | 19% | 25% |

Comments on this post from women only, please. If you identify as a woman, you are welcome to comment on this post. If you don’t, please sit this one out. Thank you. Comments will be moderated to this effect, to the best of my ability.

[Chantal Joffe – “Poppy, Esme, Oleanna, Gracie, and Kate”]

That’s the question Helen Beebee, professor of philosophy at the University of Manchester, takes up in a recent essay in The Philosopher’s Magazine.

One thing Professor Beebee notes is that some of the problems, as well as some of the improvements, regarding the representation of, treatment of, and experiences of women in philosophy, are reflections of the broader culture:

Professor Beebee says, “That’s not an earth-shattering improvement, but it’s definitely progress—and I’m optimistic that much more progress can be made.”

You can read the whole article here.