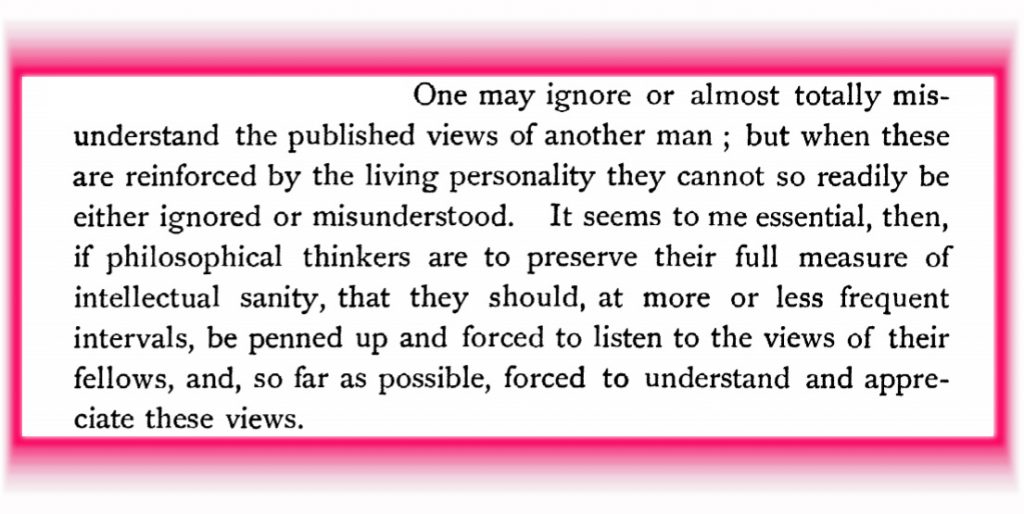

This seems as if it was written for our era, in which an important problem of public discourse is its focus on snippets of speech and ideas detached from knowledge of their context, their motivation, and the whole person behind them, reattached instead to easy assumptions and convenient caricatures for polemical purposes. That picture currently characterizes social media more than it does academic exchanges, but it is a fantasy that the latter can be entirely insulated from the influence of the former. So why not make use of the conventions of academia—including in-person conferences—to push for the kind of discourse we want to see more of?

In my experience, these benefits are strongest in smaller conferences that extend over several days with few or no parallel sessions, during which it is expected that most or all of the participants will be at most or all of the sessions. I think this is in part owed to the sense that your presence is noticed, which may lead to a feeling of obligated attention. I’m not going to say it is impossible to get these benefits through online interactions. It’s enough, I think, to say that the technology of online conferences and the norms around their use seem to make presence, attention, and participation more optional, and less likely to produce the goods we get from being “penned up and forced to listen.”

(Thanks to Nathan Ballantyne (Fordham), for bringing the Creighton quote to my attention. It is from a version of Creighton’s address, “The Purposes of a Philosophical Association,” published in The Philosophical Review vol. 11, no. 3, in May 1902.)

There has been a fair amount of discussion of the future of in-person academic conferences. The COVID-19 pandemic has acclimated us to online meetings and events. Some have argued that online should be the new default for academic events, and have provided guidance and models as to what online conferences could be like (some of which predates the pandemic) and descriptions of what other academic events videoconferencing technology makes possible or easier.

As I’ve said before, I think it would be bad if in-person conferences became permanently rare. One thing I mentioned are “the professional friendships that develop by being in the same place for for an extended period of time, talking philosophy but also getting to know each other as persons, which in turn can inform, enrich, and encourage subsequent philosophical interactions.”

But there are other reasons, one of which was offered by J.E. Creighton, the first president of the American Philosophical Association (APA), in his 1902 presidential address:

There is indeed something to being in a room with a person, being able to ask them questions but in a way beneficially constrained by the norms of professionalism, that is conducive to greater mutual understanding. And there’s something to the conference setting, which allows time for more relaxed interactions between more than just the academic part of our selves—more of the whole person—that can encourage a kind sociality that makes us better listeners of each other’s ideas.