He saw in this heartbreak a miniature of the whole — the intricate interlacing of creaturely destinies on a planet of finite resources, growing populations, and infinite interconnectedness of needs.

Writing shortly before he became National Director of Planned Parenthood — a position he would hold for more than a decade in parallel with his conservation work — Vogt adds:

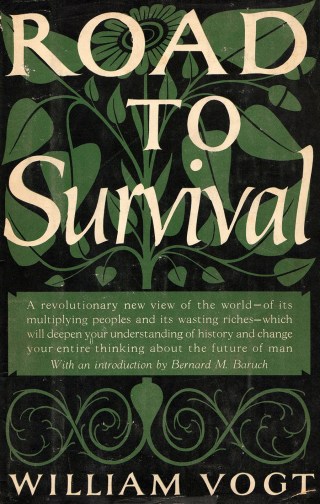

Vogt spent the next decade and a half developing these ideas by devouring countless books and scientific papers, talking with scientists and sea captains, farmers and diplomats, presidents and sheepherders in Patagonia, engineers and trappers in Manitoba. In 1948 — the year the great nature writer Henry Beston cast his poetic hope that “perhaps there is still time to take a stand for the Kingdom of Life [which] needs defenders” and that “perhaps, mighty as its enemies may be, allies will come who are even mightier” — Vogt distilled his learnings in Road to Survival (public library), a mighty manifesto that roused a generation of allies to stand for the Kingdom of Life.

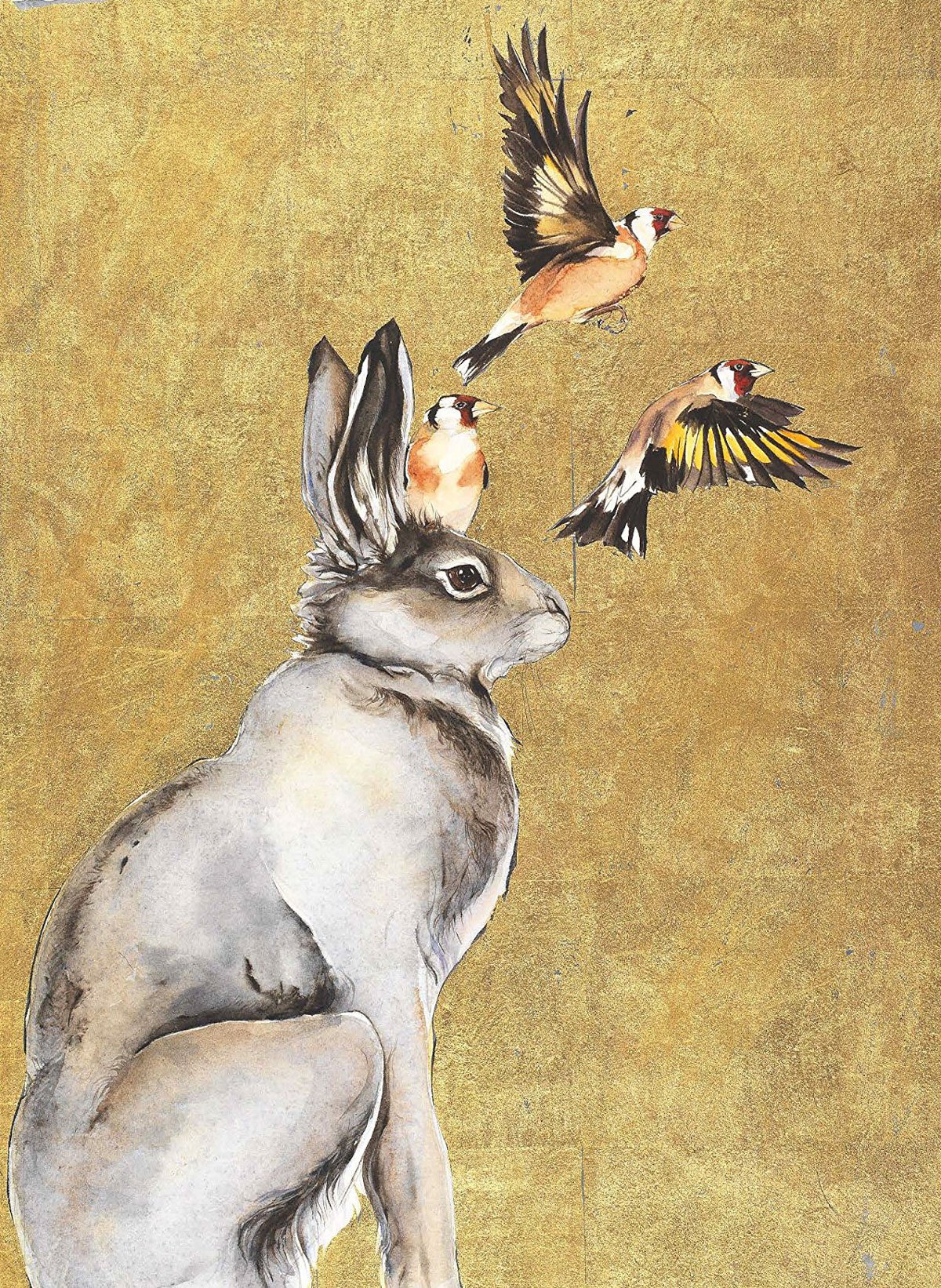

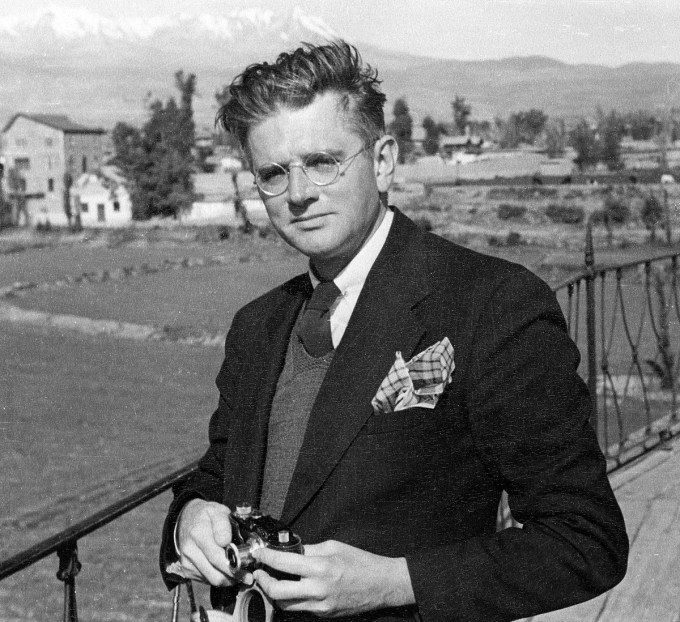

Literature remained his portal into life as he set out on a literary career in New York. But nature beckoned, the birds beckoned.

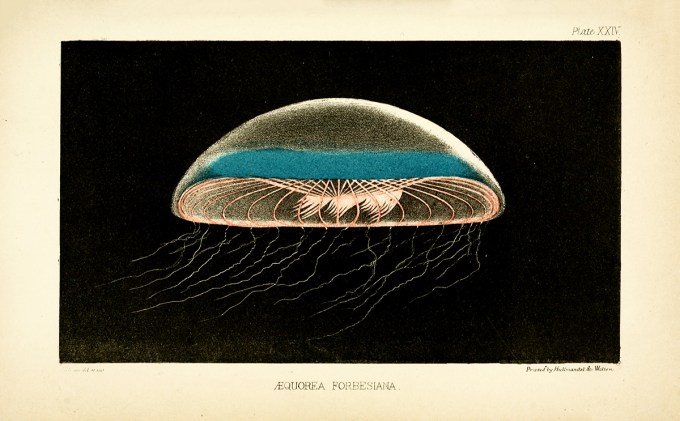

At thirty, Vogt abruptly left the city for Latin America, traveling on a Peruvian commission to study bird populations on the guano islands. In the three years he spent there, laboring in the salty air on the hot barren rocks, he arrived at an empirical proof of Muir’s insight — Vogt discovered that when changes in ocean currents diminished the population of plankton and anchovies, millions of birds fled the islands in search of food, leaving their defenseless chicks to die in “pitiful, collapsed, downy clumps” that broke his heart.

During his long recovery from paralytic polio as a child, William had fallen in love with the natural world, escaping his confinement through books about the wilderness and its wondrous creatures. A century before the Oxford Children’s Dictionary discarded dozens of words related to nature as irrelevant to the imagination and its prosthesis in language, the small bedridden boy grew especially enchanted by the feathered creatures of free flight that he met on the page.

In a chapter aptly titled “History of Our Future,” Vogt writes:

Especially do I mean men and women in overpopulated countries who produce excessive numbers of children who, unhappily, cannot escape their fate as hostages to the forces of misery and disaster that lower upon the horizon of our future.

A century after the trailblazing conservationist John Muir observed that “when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” and half a century before Maya Angelou urged us in her cosmic clarion call to see that “we, this people, on this minuscule and kithless globe” must correct our course before we destroy ourselves and our kith-hitched globe, the ecologist and conservationist William Vogt (May 15, 1902–July 11, 1968) composed a masterwork of admonition and actionable vision that shaped the ethos of the modern environmental movement and emboldened the generation of pioneers who set it into motion.

In an admonition of astonishing prescience, Vogt insists that changing the trend requires revising our past ideals to calibrate them to an evolving ecological reality:

We must — all of us, men, women, and children — reorient ourselves with relation to the world in which we live… We must come to understand our past, our history, in terms of the soil and water and forests and grasses that have made it what it is. We must see the years to come in the frame that makes space and time one.

When I write “we” I do not mean the other fellow. I mean every person who reads a newspaper printed on pulp from vanishing forests. I mean every man and woman who eats a meal drawn from steadily shrinking lands. Everyone who flushes a toilet, and thereby pollutes a river, wastes fertile organic matter and helps to lower a water table. Everyone who puts on a wool garment derived from overgrazed ranges that have been cut by the little hoofs and gullied by the rains, sending runoff and topsoil into the rivers downstream, flooding cities hundreds of miles away.

In an era when humanity regarded the rest of nature as a world parallel to our own — a world at best visited in pleasant excursions, at worst reduced to extractable resources to serve human needs — Vogt insists that “ecological health is one of the indispensables” in the “flowering of human happiness and well-being.” A century after Ernst Haeckel coined the term ecology and a decade before Rachel Carson made it a household word, Vogt draws on his island discovery to contour the totality of Earth’s ecological interdependence:

In a world he considered already overcrowded and resource-strained by the two billion people inhabiting it — a population that would triple within a generation — Vogt adds:

Half a century after Alfred Russel Wallace issued his prophetic prescription for civilizational course-correction — an admonition that fell on deaf ears at the outset of the twentieth century and would remain a point of willful deafness in the climate denial of the twenty-first — Vogt makes an impassioned and empowering appeal to the only substantive force of change in the grand scheme of any society and civilization:

Half a century after Alfred Russel Wallace issued his prophetic prescription for civilizational course-correction — an admonition that fell on deaf ears at the outset of the twentieth century and would remain a point of willful deafness in the climate denial of the twenty-first — Vogt makes an impassioned and empowering appeal to the only substantive force of change in the grand scheme of any society and civilization:

For a contemporary counterpart to Vogt’s Road to Survival, see the excellent anthology of policy, poetry, and science All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, shining a kaleidoscope of actionable perspective by women leading the way on the road Vogt envisioned, then revisit Eve Ensler’s extraordinary letter of apology to Mother Earth.

[…]