We are born wonder-stricken by the glory of nature — it can only be so, for we ourselves are living wonders, sentient somethings against the staggering odds of nothingness — and yet we so readily relinquish this natural bond at the altar of a culture that tells us what it means to grow up. This loss might be our great primal wound.

“The trees, sunrise and sunset — the lake the moon and the stars… the poets have been right in these centuries,” Lorraine Hansberry wrote as she reached for the surest salve from the pit of her depression.

In Handbook of Nature Study, Comstock observes that beyond the “practical and helpful knowledge” of the forces and phenomena that animate this world — knowledge that equips us with singular self-reliance — intimacy with nature confers upon us, child and grown child alike, larger and more abstract powers of mind, trining in us that vital balance of reason and imagination:

Nature-study cultivates the child’s imagination, since there are so many wonderful and true stories that he may read with his own eyes, which affect his imagination as much as does fairy lore; at the same time nature-study cultivates in him a perception and a regard for what is true, and the power to express it. All things seem possible in nature; yet this seeming is always guarded by the eager quest of what is true. Perhaps half the falsehood in the world is due to lack of power to detect the truth and to express it. Nature-study aids both in discernment and in expression of things as they are.

Perhaps if a fly were less wonderfully made, it would be a less convenient vehicle for microbes.

Writing in an era still haunted by extreme and antiscientific religiosity denying the entropic reality of life and death with the lulling mythos of immortality, Comstock makes a bold, simple point about how observing the rest of nature inures us to the elemental fact of our own mortality, even as children — a kind of mental hygiene, an antidote to cowering behind dogma and delusion:

A generation after astronomer Maria Mitchell swung open the portal of possibility in higher education for women, Anna entered Cornell University to study zoology, botany, and other natural sciences. She took an entomology course with John Henry Comstock, whose work laid the foundation for the modern classification of butterflies, moths, and scale insects. To both of their surprise and mutual delight, they fell in love. Three years later, without graduating, she married him. In another three years, she returned to Cornell to finish her studies, emerging with a degree in natural history. She went on collaborating with John on joint entomological studies and illustrating his works.

Above all, the book is an antidote to desensitization, an act of resistance to the culture-conditioned ways we have of taking for granted that which grants us life. In its final pages, devoted to astronomy, Comstock writes:

For decades, Comstock met with hundreds of New York State public school teachers and administrators, trying to persuade them to include a course in “nature-study” into their curricula. She was met with indifference and was told that children had to be taught more valuable skills — skills that would make them better equipped for the workforce, that savage engine of production and consumption. (A century hence, we are watching young people rise from the engine’s miasma, frightened and ferocious for change, to face the ethical and ecological cost of that indifference — because the cost of all indifference is always the loss of something worth loving.)

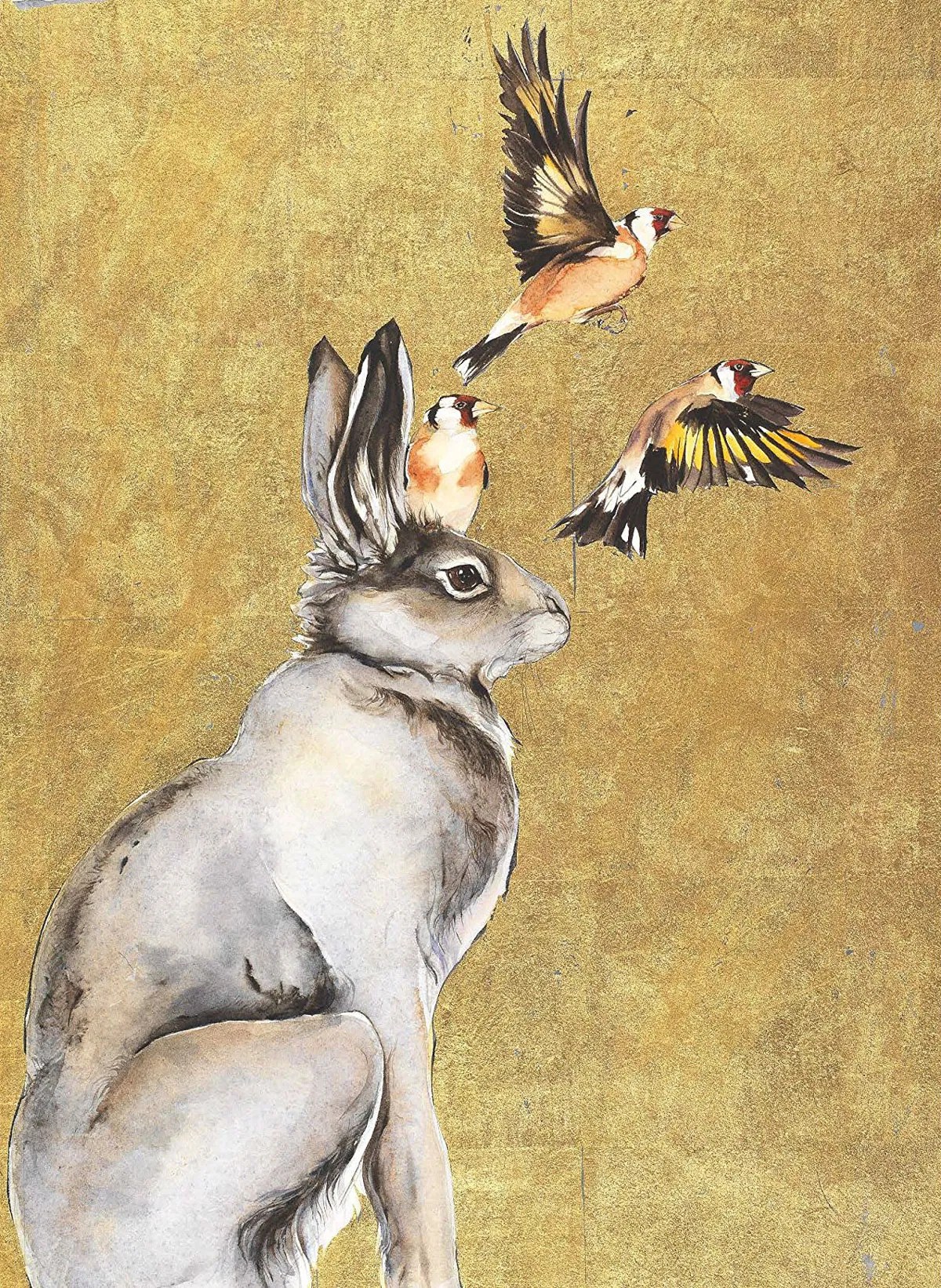

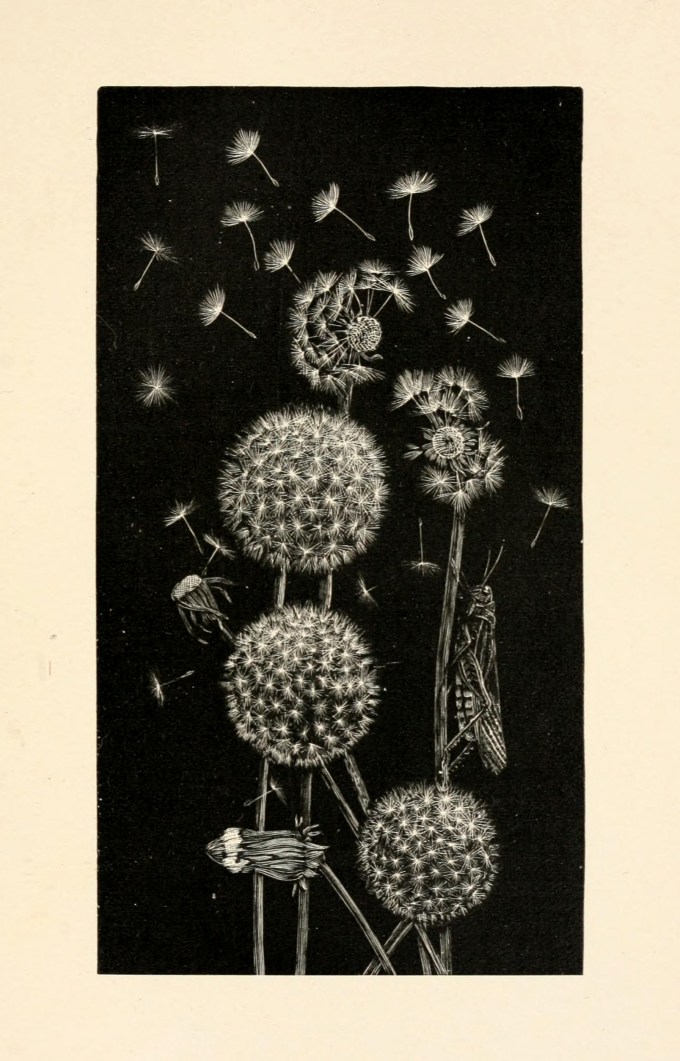

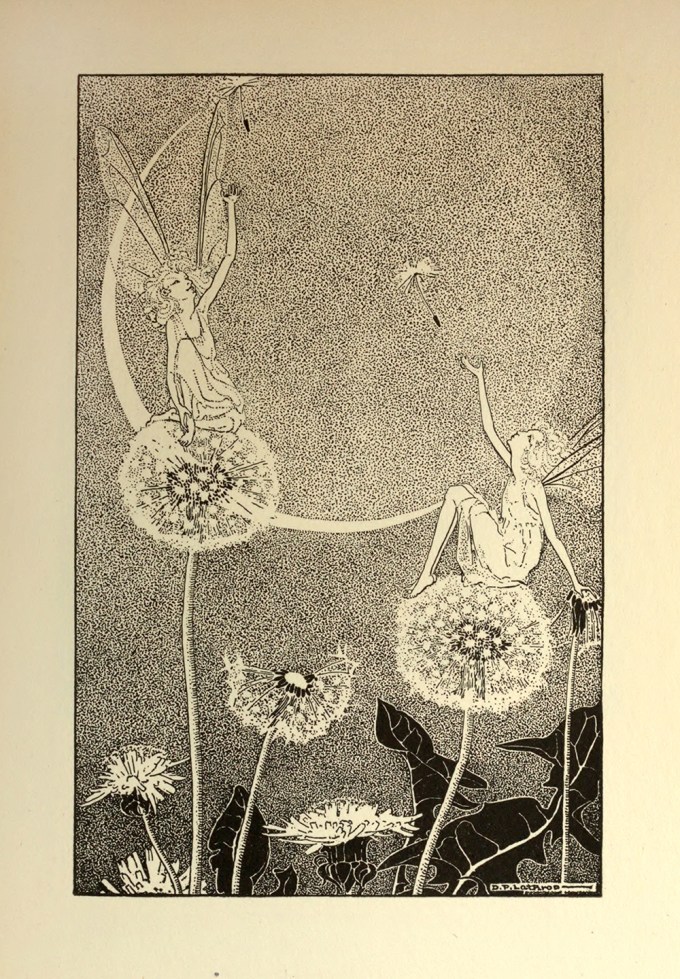

A century before the Oxford Children’s Dictionary dropped fifty nature-words as irrelevant to modern children’s lexicon and imagination, a century before young people rose up by the millions to undo the past’s disregard for nature that imperils their future, Comstock insisted that “it is a great asset to the conservation of our natural resources to have the children of our land be interested in the wild life in such a chummy and intimate manner.” Half a century before Rachel Carson awakened the modern ecological conscience with her scientific-poetic ethos that “there is in us a deeply seated response to the natural universe, which is part of our humanity,” Comstock highlighted our kinship with microbe and mammoth, with dolphin and dandelion, believing that an understanding of this interdependence would awaken in us “a sensible altruism and humanness” to bring into our relationship with nature — which is, at bottom, our relationship with ourselves and each other.

Anna had no formal training as an artist, but she had long dwelled in nature’s beauty, having entered it through the twin doorways of science and literature — Emerson, Wordsworth, and Thoreau in particular. Having so magnetized her attention to the delicate details that consecrate life with aliveness, she began observing insects under the microscope, taught herself to illustrate what she saw, and eventually enrolled in Cooper Union to refine her draughtsmanship as a wood engraver. She went on to engrave more than 600 plates of insects, some of which were exhibited in the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago and the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, and became one of the first women admitted to Sigma Xi — the Scientific Research Honor Society that has included more than 200 Nobel laureates, Einstein, Watson, and Crick among them.

That, indeed, is the book’s great gift — a lovely reminder that to move through the world unstaggered by life is the only death.

“Children in wonder watching the stars, is the aim and the end,” Dylan Thomas wrote in his spare, stunning poem about trees, truth, and the human animal’s most self-savaging loss of perspective.

When the early twentieth century clawed at the wound with its increasingly industrialized model of education, preparing children for lives of conspicuous consumption and nursing them on the illusion of nature as a parallel worlds, the artist, naturalist, philosopher, entomologist, and educator Anna Botsford Comstock (September 1, 1854–August 24, 1930) set out to provide an antidote in her wonderful Handbook of Nature Study (public library | public domain).

Paths that lead to the seeing and comprehending of what [the child] may find beneath his feet or above his head… whether they lead among the lowliest plants, or whether to the stars, finally converge and bring the wanderer to that serene peace and hopeful faith that is the sure inheritance of all those who realize fully that they are working units of this wonderful universe.

But Comstock persisted. When she became Cornell’s first female professor, she piloted an experimental nature-study course, which was soon approved and implemented statewide. Handbook of Nature Study — the culmination of her life’s work — has accomplished the rare triumph of remaining in print for more than a century, attesting to the timelessness of its ethos and its need. Coursing through it is Comstock’s largehearted, infectious love of the living world. A century after Blake reverenced the common fly in his short existentialist poem, she offers an affectionate exculpation of this creature we indict as a disease-carrying menace, rapturously detailing its delicate anatomy — from the crowning curio of its head, “two great, brown spheres… composed of thousands of tiny six-sided eyes that give information of what is coming in any direction,” to the tiny tender claws with which the fly “walks on its tiptoes” — concluding:

Beyond cultivating our “love of the beautiful,” beyond refining our sense of “color, form, and music,” immersion in and understanding of nature attunes us to our larger belonging:

In 1911, she condensed her lifelong animating ethos in Handbook of Nature Study.

She saw children as children, pure-hearted and large-eyed with wonder. She saw them as emissaries of the forgotten parts of ourselves and as “future citizens.” And so everything she wrote that references the child can be read as addressing each one of us — for, as Wild Things creator Maurice Sendak knew, the most difficult and rewarding triumph of adulthood is “having your child self intact and alive and something to be proud of.” (This elemental truth is why I cherish “children’s” books as incomparable existential handbooks to self-knowledge and reality-knowledge — training ground for attentive intimacy with nature and its expression in human nature — and why I occasionally write some.)

Perhaps the most valuable practical lesson the child gets from nature-study is a personal knowledge that nature’s laws are not to be evaded. Wherever he looks, he discovers that attempts at such evasion result in suffering and death. A knowledge thus naturally attained of the immutability of nature’s “must” and “shall not” is in itself a moral education. The realization that the fool as well as the transgressor fares ill in breaking natural laws makes for wisdom in morals as well as in hygiene… It is not only during childhood that this is true, for love of nature counts much for sanity in later life.

If, only once in a century, there came to us from our great sun light and heat bringing the power to awaken dormant life, to lift the plant from the seed and clothe the earth with verdure, then it would indeed be a miracle. But the sun by shining every day cheapens its miracles in the eyes of the thoughtless.