Music is closely intertwined with the life of every race. We understand the people better if we know their music, and we appreciate the music better if we understand the people themselves.

Everywhere she went, her pure-hearted devotion to preserving traditional music magnetized the warmth of the community. The eminent Sioux elder Red Fox adopted her as a daughter.

Frances Densmore (May 21, 1867–June 5, 1957) — a young music teacher from Red Wing, Minnesota — was appalled. In consonance with the eternal truth that the best way to complain is to create, she set out to singlehandedly preserve a vital aspect of indigenous culture, the one art that is the heartbeat of every culture: music.

Tucked into a corner of the Library of Congress is the Densmore Collection of cylinder phonographs — a bygone medium containing the living songs of an ancient culture.

With her simple box camera and cylinder phonograph, wearing trousers and a bow-tie, Frances Densmore spent years traveling to remote settlements where no scholar dared venture. She worked with dozens of tribes — the Sioux, the Chippewa, the Mandan, the Hidatsa, the northern Pawnee of Oklahoma, the Winnebago and Menominee of Wisconsin, the Seminoles of Florida, the Ute of Utah, the Papago of Arizona, the Pueblo Indians of the southwest, the Kuna Indians of Panama, and various tribes across the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia.

The radical difference between the musical custom of the Indian and our own race is that, originally, the Indians used song as a means of accomplishing definite results. Singing was not a trivial matter, like the flute-playing of the young men. It was used in treating the sick, in securing success in war and the hunt, and in every undertaking which the Indian felt was beyond his power as an individual. An Indian said, “If a man is to do something more than human he must have more than human power.” Song was essential to the putting forth of this “more than human power,” and was used in connection with some prescribed action.

One of the musical requirements of the white race is that a song and its accompaniment shall be “exactly together,” but an Indian song may be either a little faster or a little slower than the accompanying drum without disturbing the Indian musician. The Indian takes his music seriously and has nothing that corresponds to our popular songs. There are standards of excellence in his music and he practices in order to attain them, although Indians do not have musical performances corresponding to our concerts. The Indians have no melody-producing instruments except the flute, which has its special uses, so the voices of the singers around the drum are like the melody-producing instruments in our orchestras or bands, while the drum is like the bass or percussion instruments which supply the rhythm. The singers and the drum provide the music at all dances and social gatherings as well as at the tribal ceremonies. They have rehearsals, as we do, and practice and learn new songs. If a man goes to visit another tribe he tries to remember and bring home songs, which are always credited to the source whence they came. Songs are taught to one person by another, and in the old days it was not unusual for a man to pay the value of one or two ponies for a song. He did not buy such a song for his own pleasure but because it had a ceremonial connection or was believed to have magic power. To this class belong the songs for treating the sick and those believed to bring rain.

Word of her work had spread beyond academic journals. In 1907, the Smithsonian approached her to make recordings for their Bureau of American Ethnography. Within a year, she had compiled her recordings in the popular LP Healing Songs of the Native Americans.

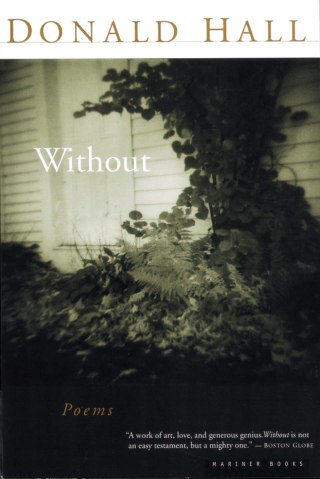

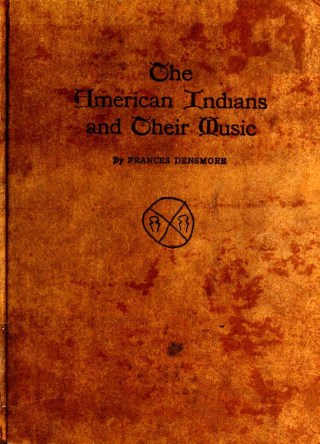

To use an ahistorical term she far predates, Frances Densmore became the premiere ethnomusicologist of her time and place. She opened her 1926 book The American Indians and Their Music (public library | public domain) with an insight that reaches beyond culture, into the very heart of our species:

In some elemental sense, however, this is the selfsame function music serves in every culture since the dawn of our species: We use music to heal ourselves, to save ourselves. We have, since before we discovered the mathematics of harmony. We will, long after everything we know of civilization has crumbled into discord. Nothing refracts the light of being like music. Nothing reflects the health of a culture and nothing predicts its durability better than how well it treats its song-makers.

Thomas Edison had invented the phonograph — a mechanical means of recording and reproducing sound, using a wax-coated cardboard cylinder and a cutting stylus — when Frances was ten. Around that time, listening to the songs of the Dakota Indians near her home, she fell in love with music. In an era when higher education was closed to women with only limited exceptions, she spent three years studying music at Oberlin College — the first university to admit women, and the first to admit students of ethnic minorities — then devoted herself to teaching Western music to Native Americans (the academic term for whom was then “American Indians”) and learning their own traditional songs as they taught her in turn.

This function of music shaped its form:

Whenever Frances returned to her monastic one-room apartment, she perched at her heavy black typewriter to record her evolving understanding of a complex musical world in a way that no scholar before her had, and none since, detailing everything from children’s songs to the design of wind instruments to the spell-like songs sung as “love charms.”

In the book, she detailed the singular role of music in Native American culture, teleologically distinct from the spiritual function it served in early Western culture: