“I have marveled at the green urchins on a Maine shore, clinging to the exposed rock at low water of spring tides, where the beautiful coralline algae spread a rose-colored crust beneath the shining green of their bodies,” Rachel Carson wrote as she was revolutionizing our understanding of the marine world with her poetic science and preparing to awaken the modern environmental conscience. “At that place the bottom slopes away steeply and when the waves at low tide break on the crest of the slope, they drain back to the sea with a strong rush of water. Yet as each wave recedes, the urchins remain… undisturbed.”

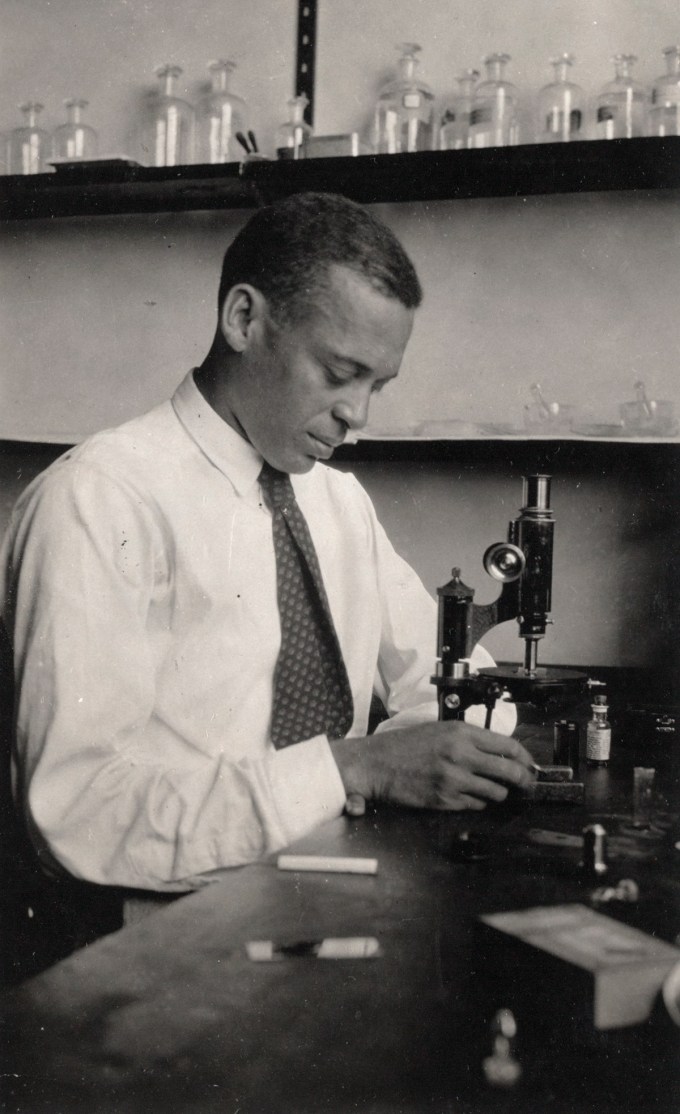

He was a scientist.

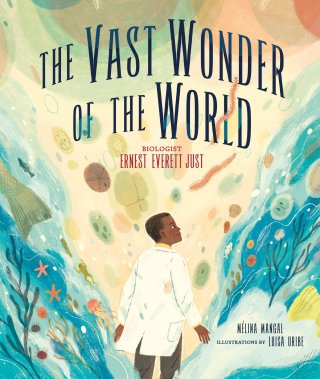

All biography is more like sculpture than like portraiture, tasked with the creative challenge of what to cut away from the immense monolith of a whole life in order to render a representative depiction of personhood — a challenge especially trying when sculpting a life-story for young readers, balancing beauty and complexity. The Vast Wonder of the World is more Grecian sculpture than Guernica, composed in the spirit of beautification and celebration — Just did, after all, live a beautiful and inspiring life — without wading into the confusions, controversies, and complexities that haunt any human life and haunted his. (My own orientation to writing nonfiction for young humans, especially dealing with science, is to lean on the side of truth; to trust that any truth, handled with basic sensitivity and humanity, is in the larger service of beauty — the beauty of reality — and that E.B. White was right in his life-tested conviction that anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time.”) The book, while lovely, ends on an abruptly and artificially upbeat note with the publication of Just’s magnum opus, leaving a great deal out: how he, like Frederick Douglass before him, fell in love with a German woman — a philosophy student — while still married; how, unlike Douglass, he had the moral courage to rise against the stigma of divorce; how the Nazis invaded Germany months after the landmark publication of his life’s work and interned him in a camp; how he was soon released and headed back to America, not knowing his own cells had been silently mutating along the way; how within months of his return he was dead by that metastatic mutation, leaving behind the stunning urchin spine of his trailblazing life and his life-redefining science.

The story begins in Woods Hole in 1911:

Despite the scientific esteem the discovery brought him, Just felt increasingly stifled by the swell of racism in his nation’s bosom, which kept him from obtaining a teaching position at a major university worthy of his talent and credentials. (Since history is not the factual record of events but the dramatic narrative our species superimposes over events, it is historical irony, in the classic Ancient Greek literary sense, that Just was among the biologists whose work laid the foundation for genomics and its sobering revelation that we share 98% of our DNA with a head of broccoli, dwarfing to absurdity the sub-negligible biological differences on which humans peg the artificial othernesses of their senseless biases.)

He became a biology professor. He traveled to Woods Hole each summer to deepen his research and train young scientists. In an era when most biologists treated marine creatures as inanimate samples for study, he tenderly removed sea urchins and sand dollars from their habitat to transport them to the lab and encouraged his students to study them right there in the tide pool.

Special thanks to my friend Stephon Alexander for bringing Ernest Everett Just’s story into my life.

But Ernest Everett Just was not like other scientists. Half a century after another researcher with a similar name and a similar scientific passion (the German marine biologist Ernst Haeckel) coined the word ecology and half a century before another marine biologist with similar outsider status (Rachel Carson) made it a household word, Ernest Everett Just “saw the whole, where others saw only parts.” Like Carson, he wrote poetry — that supreme art of interrelation; like every true visionary, he was above all a noticer — “he noticed details others failed to see.”

Born not long after the development of cell theory began revolutionizing our understanding of life, at a time when the cell was known to be the basic biological unit but its working parts were a mystery, Just devoted the rest of his cellular existence to illuminating the mystery.

For other lovely picture-book biographies of science visionaries who broadened the humanistic landscape of possibility with the example of their lives, savor the illustrated lives of astronomer Maria Mitchell and astronaut Ronald McNair, then revisit the inspiring story of Wangari Maathai, who became the first African woman to win the Nobel Prize with her tenacious work at the intersection of activism and ecology.

He knew the ways of the sea, though he was not a fisherman. His grandfather had built wharves, but he was not a dockworker…

So too with deepest discoveries of science, adhering to the bedrock of culture ideas that remain through the ebb and flow of ideologies. So too with the minds who produce them — the rebels, the visionaries, the pioneers who stand strong and undisturbed against the tide of their time.

At twilight, a man lay on a dock, luring marine worms with a lantern. He scooped them out with his net and placed them in a bucket. He couldn’t wait to look at them more closely.

Ernest Everett Just (August 14, 1883–October 27, 1941), who soon came to be admired as the “black Apollo” of science by the Italian women working at the Neapolitan laboratory for which he left Woods Hole, is the subject of The Vast Wonder of the World (public library) by librarian-turned-author Mélina Mangal and Colombian illustrator Luisa Uribe — a lovey addition to the growing corpus of picture-book biographies of cultural heroes to foment young hearts with inspiration for growing vast minds and tenacious spirits.

Along the way, we see his mother’s school destroyed by a fire, we see Ernest leave home on a segregated steamship to continue his education in the North, we see him study with grief-redoubled focus after his mother dies of tuberculosis.

Exactly twenty years before Carson began honing her urchin mind at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts — the JPL of marine biology — a young fellow urchin alighted there to do the same.

In his mid-forties, Just emigrated to Europe, where he completed and published the groundbreaking results of his research as the twin triumphs Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Animals and The Biology of the Cell Surface, both published in 1939, as the world’s deadliest war was syphoning life from humanity and syphoning the humanity from Life.

At Dartmouth, a biology class concentrates and consecrates his devotion to science as he looks through a microscope for the first time and discovers the miniature universe of the cell.

Day after obsessive day, night after late night, he peered at sea animals through the microscope, squinting at the edges of a radical idea, until it blazed with the empirical clarity of a discovery: Studying a sand dollar during fertilization, he observed how the egg cell was directing its own development — anathema to the accepted view that the sperm cell was responsible for the changes that coalesce into new life.

The story follows him from his childhood in South Carolina — where he watched the river become ocean, attended the school his mother founded in the town she established, and nearly lost his life to typhoid fever — to the laboratory where he developed his greatest scientific contribution: the understanding of how life begins from an egg.