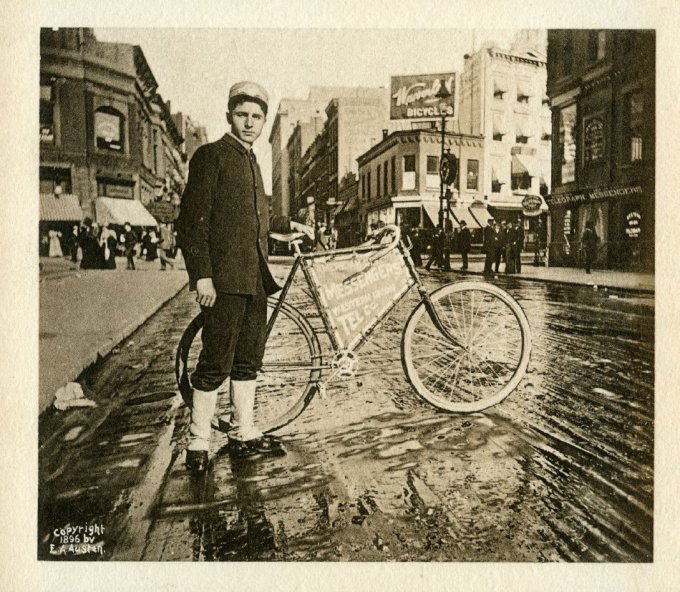

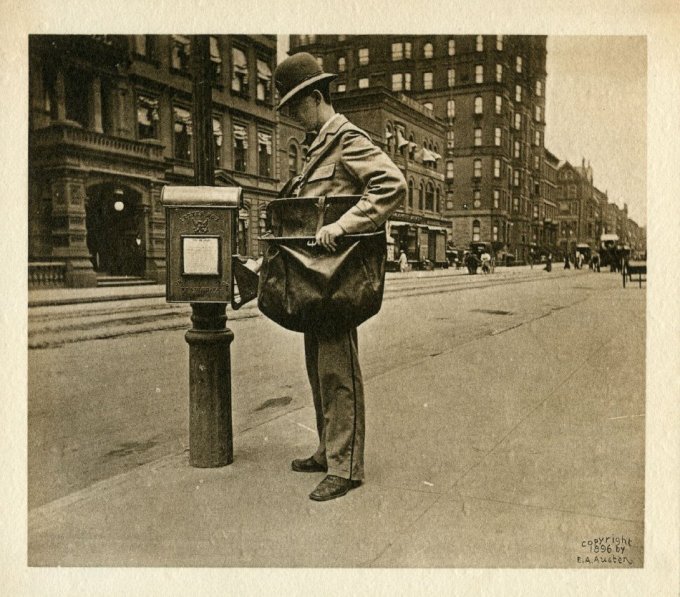

Turning a closet into a darkroom, Alice proceeded to teach herself the art of photography, taking meticulous process notes to refine her technique. Not yet out of her teens and already one of the most accomplished photographers in America, she ventured out into world to document its vibrant life, dedicating hers to her art. In an era when almost no women practiced photography — an activity both intensely physical and intensely delicate, given the size, weight, and fragility of early cameras and glass plates — she became the first American woman known to work outside the studio, creating what we now know as street photography.

Shortly after the opening, Alice suffered a stroke. By spring, she was dead. Gertrude survived her by a decade, living to ninety. The couple had expressly wished to be buried together — a wish Gertrude’s family bluntly refused in one final act of assault on their lifelong devotion.

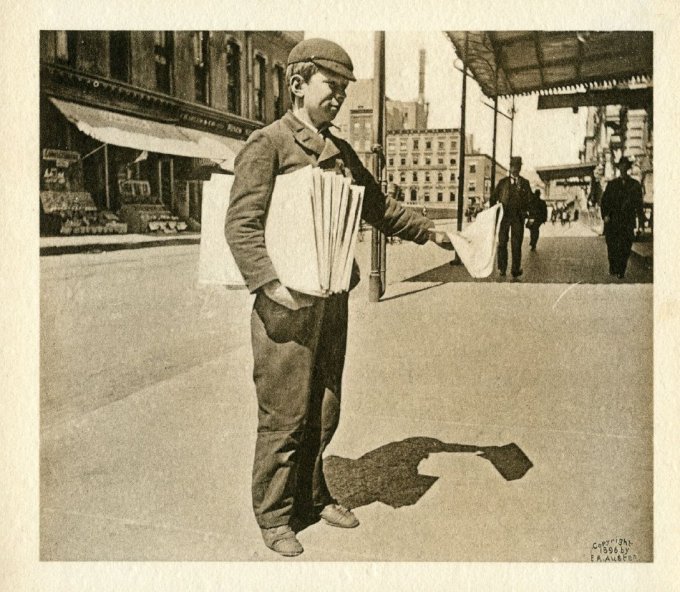

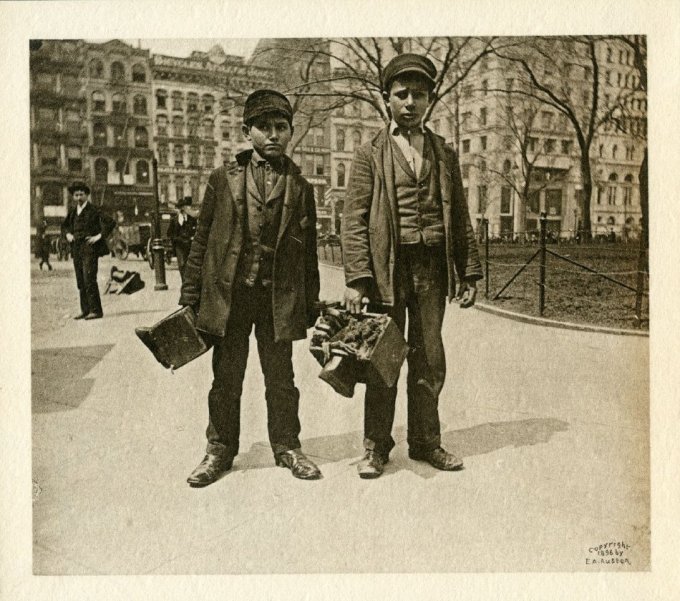

Over her long life, Alice Austen took more than 8,000 photographs, turning her sensitive and daring lens toward the lives of immigrants, child laborers, New York “street types,” and people for whom Victorian culture had neither terms nor tenderness and whom we might call LGBT today.

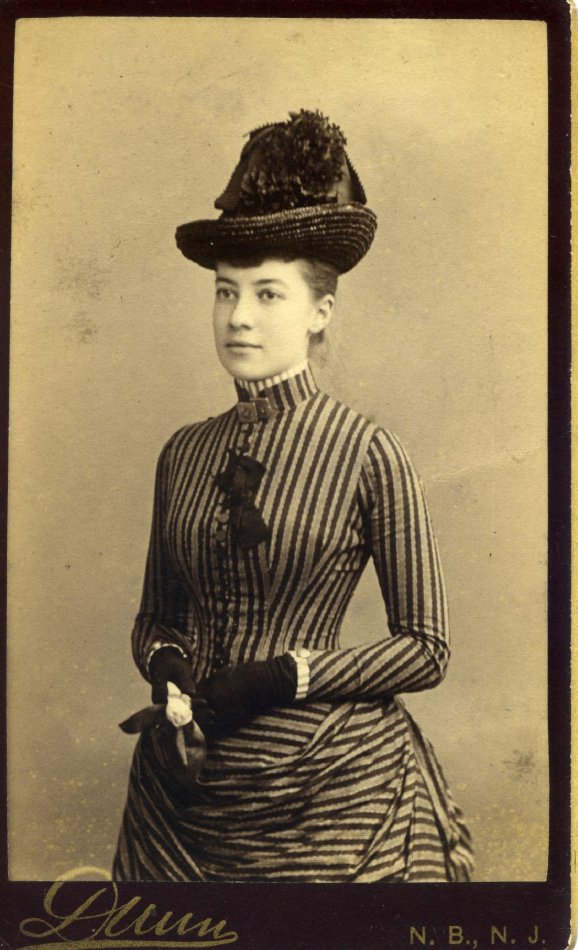

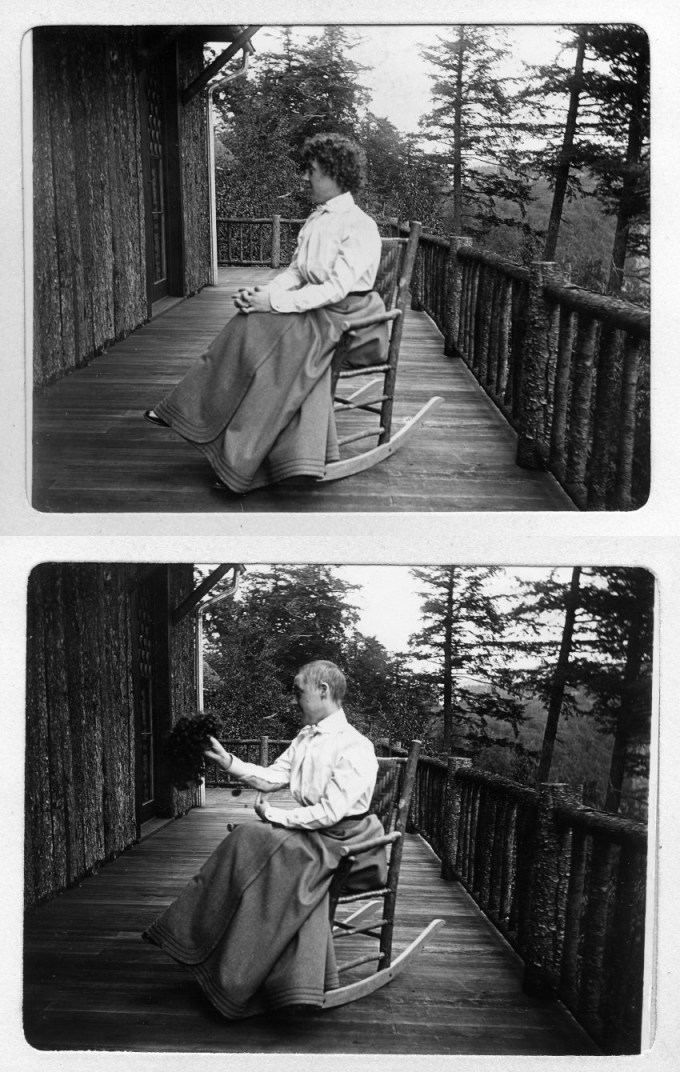

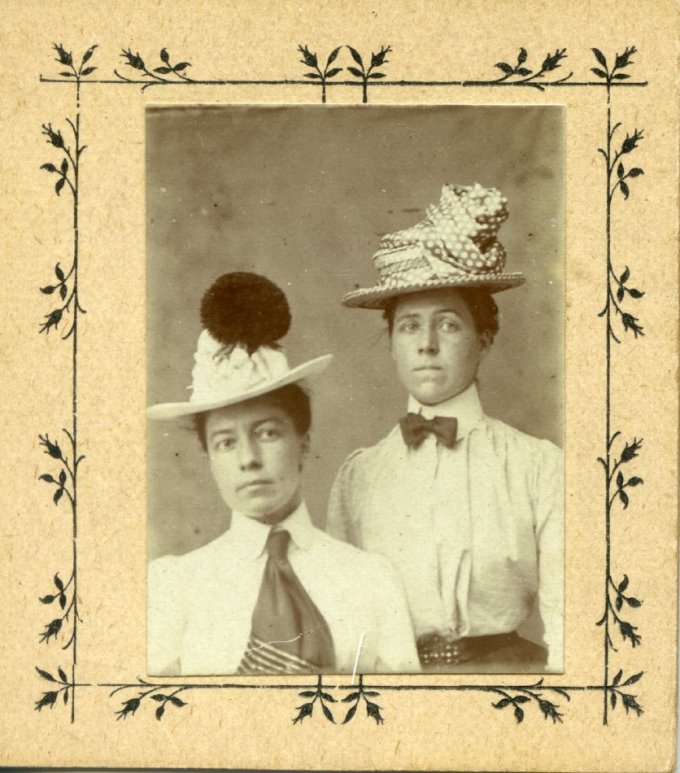

In the final months of the nineteenth century, Alice Austen took a summer vacation in the Catskill Mountains, where she met Gertrude Tate, six years her junior — a vivacious dance instructor and kindergarten teacher from Brooklyn, who wore a wig over her buzz-cut hair and with whom Alice would spend the remaining fifty-three years of her life.

As the ferry traverses the East River, Alice is watching the Statue of Liberty rise imperturbable over Ellis Island, where has just photographed people at New York Harbor’s immigrant quarantine stations — something she did every year for a decade, returning to that crucible of humility and hope to document those tender and terrifying moments when lives are begun afresh with little more than wordless daring and a fragile dream.

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Alice was flung into financial struggle. By the end of WWII, she and Gertrude were evicted from the home they had shared for three decades and thrust into the hands of their respective extended families, none of whom approved of their lifelong relationship. Without means and without options, they were separated. Gertrude was taken to Queens. At eighty, Alice ended up at the Staten Island Farm Colony — the euphemistic name for the local poorhouse. Gertrude, who continued teaching dance well into her seventies, visited weekly.

Emerging from her photographs is a lovely testament to Frederick Douglass’s faith in early photography as an instrument of social justice, bridging the ideal and the real.

As a girl, abandoned by her father before her birth and raised by her mother in a cottage by an enormous sycamore rising strong despite the blackened interior hollowed out by lightning, Alice had watched Lady Liberty being built, part emblem and part promise. The statue was dedicated the year Emily Dickinson died and Alice turned ten — the year her uncle, a sea-captain, gave her a dry-plate camera from England as a birthday present.

A generation before Berenice Abbott, another trailblazing lesbian photographer, created her iconic series Changing New York, Alice Austen captured the changing face of the city — this ever-changing emblem of a city — during its most rapid period of transformation as modernity was finding its sea legs and America was becoming America.

Today, the Staten Island home the couple shared for most of their life, the cottage in which Alice grew up and mastered her art, survives as Alice Austen House — part museum and part memorial, celebrating Alice’s trailblazing art and the totality of being from which it sprang, including her lush love for Gertrude. The sycamore tree — one of the sylvan marvels in Benjamin Swett’s wonderful book New York City of Trees (public library), from which I first learned of Alice Austen’s story — still rises by the house, still charred and hollowed, still growing and lush with life.

Drawing on his magazine connections, he secured publication of Alice’s work in Life, which raised enough funds to migrate her to a nursing home. He then built on the initial visibility to organize an exhibition of her work at a local museum in 1951 — the first and only in her lifetime. When the show opened on October 7, now celebrated as Alice Austen Day, Alice was there with Gertrude by her side.

So began the other great Gertrude-and-Alice love story — far less fabled than the one of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas a generation later, but also one in which two people, joined together, become themselves.”

Like Vivian Maier — another visionary photographer who also captured the street life of the city and who also, by the scant surviving evidence, was very probably queer — Alice Austen lived out her life without artistic recognition. Like Maier’s work, Austen’s was brought to light by a man who chanced upon it and knew he had chanced upon greatness. Unlike Maier, Austen was still alive.

Riding the Manhattan-bound ferry that day in her youth, Alice didn’t yet know — for we never know these things — that she was soon to meet the love of her life.

She has mounted fifty pounds of photography equipment on her bicycle and is pedaling along the shore to the Staten Island ferry, headed for Manhattan. Photography is only a generation old and Alice Austen (March 17, 1866–June 9, 1952) is twenty-nine. She is about to take photographs of the proper technique for mounting, dismounting, riding, and carrying a bicycle for her friend Maria’s trailblazing manifesto-manual for cycling, inciting Victorian women to embrace the spoked engine of emancipation: “You are at all times independent. This absolute freedom of the cyclist can be known only to the initiated.”

Alice — artist, athlete, banjo player, sailor, founder of the Staten Island Garden Club, the first woman to own a car in the borough — has come as close to absolute freedom as a woman of her era could come, transcending the narrow roadways of her time with her wheels, her lens, and her love.

In 1950, while working on his book The Revolt of American Women, Oliver Jensen — a thirty-six-year-old former Life magazine editor and writer — discovered 3,500 of Alice’s glass-plate negatives in the basement of the Staten Island Historical Society and was instantly taken with their uncommon genius. Leafing through phone books, he was staggered to realize that Alice was still alive, then doubly staggered to learn that she was living at a poorhouse.