The apple is the commonest and yet the most varied and beautiful of fruits… A rose when it blooms, the apple is a rose when it ripens. It pleases every sense to which it can be addressed, the touch, the smell, the sight, the taste; and when it falls in the still October days it pleases the ear [when] down comes the painted sphere with a mellow thump to the earth, towards which it has been nodding so long.

Noble common fruit, best friend of man and most loved by him, following him like his dog or his cow, wherever he goes. His homestead is not planted till you are planted, your roots intertwine with his; thriving best where he thrives best, loving the limestone and the frost, the plough and the pruning-knife, you are indeed suggestive of hardy, cheerful industry, and a healthy life in the open air. Temperate, chaste fruit! You mean neither luxury nor sloth, neither satiety nor indolence, neither enervating heats nor the Frigid Zones. Uncloying fruit, fruit whose best sauce is the open air, whose finest flavors only he whose taste is sharpened by brisk work or walking knows; winter fruit, when the fire of life burns brightest; fruit always a little hyperborean, leaning towards the cold; bracing, sub-acid, active fruit.

In a passage evocative of poet Diane Ackerman’s sensuous ode to the apricot, Burroughs composes a part prose poem and part love letter to the irresistible sensorium of the apple:

I think if I could subsist on you or the like of you, I should never have an intemperate or ignoble thought, never he feverish or despondent. So far as I could absorb or transmute your quality I should be cheerful, continent, equitable, sweet-blooded, long-lived, and should shed warmths and contentment around.

Burroughs has the naturalist’s talent for meeting nature on its own terms and finding beauty in its living realities, rather than appropriating them for poetic metaphor alone; when he does come to metaphor, it is a lovely and living one:

The genuine apple-eater comforts himself with an apple in their season as others with a pipe or a cigar. When he has nothing else to do, or is bored, he eats an apple. While he is waiting for the train he eats an apple, sometimes several of them. When he takes a walk he arms himself with apples… He dispenses with a knife. He prefers that his teeth shall have the first taste. Then he knows the best flavor is immediately beneath the skin, and that in a pared apple this is lost.

But the apple is a benediction not only to human lives. Long before the term existed, Burroughs celebrates it as a microcosm of biodiversity — a haven for “the never-failing crop of birds — robins, goldfinches, king-birds, cedar-birds, hair-birds, orioles, starlings — all nesting and breeding in its branches.” Leaning on his ardor for ornithology, he writes:

[…]

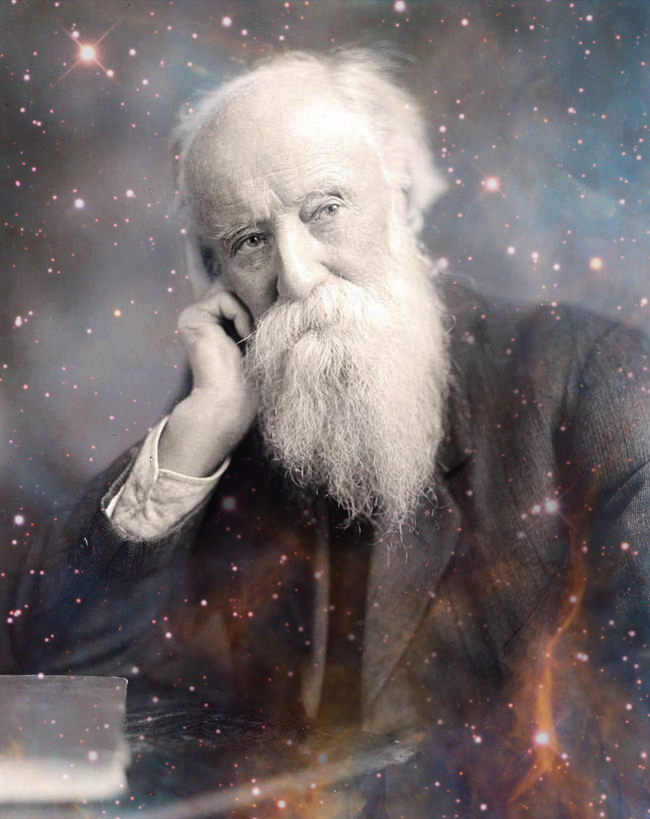

No one has written about the sensorial and spiritual splendors of the apple more beautifully, or more passionately, than the great naturalist John Burroughs (April 3, 1837–March 29, 1921) in one of the essays from his 1915 collection Sharp Eyes (public library | free ebook), which also gave us his lovely meditation on the art of noticing.

Anything, when faced with unalloyed attention, becomes a mirror. But few things have served as a mightier magnifying mirror for humanity, and for the individual human being, than the apple. Its blossoms have been selected by countless generations of pollinators in painting Earth with color. Its fruit focused the Bible story of original sin, seeding thousands of years of metaphor and myth. In the folklore of my native Bulgaria, a woman has reached the apogee of beauty when she can be likened to an apple. When British America was being settled, a land grant required settlers in the Northwestern Territory to each plant at least fifty apple or pear trees on their homestead as a kind of commitment to the land. The apple gave the greatest metropolis of Western civilization its nickname, even though most native New Yorkers don’t know the origin story of “The Big Apple.”

Complement with Burroughs on the faith of the “naturist” — his wondrous century-old manifesto for spirituality in the age of science — and his timeless wisdom on the mightiest consolation for human hardship, then revisit the little-known story of how New York City came to be known as The Big Apple.

Burroughs’s own grandfather was “one of those heroes of the stump” — the early settlers who traveled many miles on horseback for seeds and went to great lengths to protect their prized apple trees, fastening with iron bolts any storm-split trunk, even though these uncultivated pioneer trees gave only small and sour fruit. In his spirited sincerity with a wink, he serenades the apple as a cultivar of moral virtue:

Burroughs writes:

With the same passionate playfulness, Burroughs paints the apple-eater as a kind of beneficent addict:

Not a little of the sunshine of our northern winters is surely wrapped up in the apple. How could we winter over without it! How is life sweetened by its mild acids!

There are few better places to study ornithology than in the orchard. Besides its regular occupants, many of the birds of the deeper forest find occasion to visit it during the season. The cuckoo comes for the tent-caterpillar, the jay for frozen apples, the ruffed grouse for buds, the crow foraging for birds’ eggs, the woodpecker and chickadees for their food, and the high-hole for ants. The red-bird comes too, if only to see what a friendly covert its branches form; and the wood-thrush now and then comes out of the grove near by, and nests alongside of its cousin, the robin. The smaller hawks know that this is a most likely spot for their prey; and in spring the shy northern warblers may be studied as they pause to feed on the fine insects amid its branches.

How pleasing to the touch! I love to stroke its polished rondure with my hand, to carry it in my pocket on my tramp over the winter hills, or through the early spring woods. You are company, you red-cheeked spitz, or you salmon-fleshed greening! I toy with you; press your face to mine, toss you in the air, roll you on the ground, see you shine out where you lie amid the moss and dry leaves and sticks. You are so alive! You glow like a ruddy flower. You look so animated I almost expect to see you move. I postpone the eating of you, you are so beautiful! How compact; how exquisitely tinted! Stained by the sun and varnished against the rains. An independent vegetable existence, alive and vascular as my own flesh; capable of being wounded, bleeding, wasting away, and almost of repairing damages!