Without theories and without preconceived notions of what music ought to be, [the gifted listener] lends himself as a sentient human being to the power of music… We all listen on an elementary plane of musical consciousness… On that level, whatever the music may be, we experience basic reactions such as tension and release, density and transparency, a smooth or angry surface, the music’s swellings and subsidings, its pushing forward or hanging back, its length, its speed, its thunders and whisperings — and a thousand other psychologically based reflections of our physical life of movement and gesture, and our inner, subconscious mental life.

Months after Millay’s death, Harvard offered its prestigious Charles Edward Norton Professorship of Poetry for the 1951–1952 academic year to the composer Aaron Copland (November 14, 1900–December 2, 1990) — the first non-poet to hold the post since its inception a quarter century earlier. More than a decade before he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for capturing the human experience in music, Copland brought to his six lectures, later published as Music and Imagination (public library), not only the mind of an extraordinary musician but the central concern of his life — the artist’s role in the human family and the vital mutual nourishment between those who make art and those whose lives art touches, with a particular focus on the most commonly underappreciated agent in the musical universe: the gifted listener.

The poetry of music, Copland intimates, is composed both by the musician, in the creation of music and its interpretation in performance, and by the listener, in the act of listening that is itself the work of reflective interpretation. This makes listening as much a creative act as composition and performance — not a passive receptivity to the object that is music, but an active practice that confers upon the object its meaning: an art to be mastered, a talent to be honed. (In the same era, the great humanistic philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm was making the same countercultural point about the art of loving, as distinct from the damaging cultural notion of love as an object to be found and passively received.)

The power of music to move us is something quite special as an artistic phenomenon [but] I do not hold that music has the power to move us beyond any of the other arts.

Copland observes that because the process by which music gives voice to our inner lives is so delicate and complex, it becomes “a very hazardous undertaking,” for there are many points at which it can break down:

[…]

The singular power of music, as Copland conceives of it, makes me think of what it feels like to stand beneath the star-salted sky beholding the universe, with all of its immensity and intimacy — that grand cosmic silence singing with everything there is. He writes:

While elsewhere on the Harvard campus the psychologist Jerome Bruner was incubating his pioneering insight into the key to great storytelling and positing that creative writers both need and make creative readers, Copland writes:

All musicians, creators and performers alike, think of the gifted listener as a key figure in the musical universe.

The sensitive amateur, just because he lacks the prejudices and preconceptions of the professional musician, is sometimes a surer guide to the true quality of a piece of music. The ideal listener… would combine the preparation of the trained professional with the innocence of the intuitive amateur… The ideal listener, above all else, possesses the ability to lend himself to the power of music.

[…]

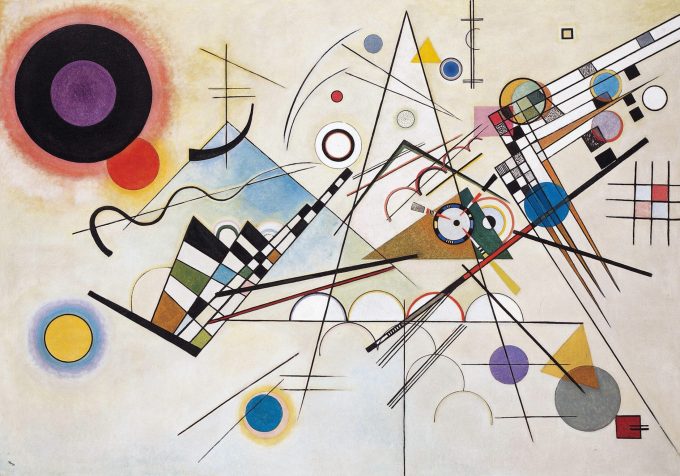

Leaning on philosopher Susanne Langer’s influential inquiry into what gives music its power and her conclusion that “music is our myth of the inner life,” Copland returns to the gifted listener as a crucial instrument for the power of music and a crucial agent in its collaborative mythmaking:

Complement this fragment of the wholly insightful Music and Imagination — which went on to inspire the young John Coltrane and an entire generation of other artists — with composer Elliott Schwartz, writing a generation later, on the seven essential skills of listening, then revisit Bob Dylan on music as an instrument of truth, Aldous Huxley on music as an instrument of transcendence, and a tender meditation on music and the mystery of aliveness.

In essence, music performs an enchanted act of subconscious storytelling. (Which might be why Maurice Sendak considered musicality the key to great storytelling.) In a sentiment at first blush inflammatory, especially for music-lovers and especially coming from a musician, Copland writes:

In essence, music performs an enchanted act of subconscious storytelling. (Which might be why Maurice Sendak considered musicality the key to great storytelling.) In a sentiment at first blush inflammatory, especially for music-lovers and especially coming from a musician, Copland writes:

“Even poetry, Sweet Patron Muse forgive me the words, is not what music is,” the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote to a friend, adding the requisite flamboyance of a 1920s radical: “Without music I should wish to die.”

The more I live the life of music the more I am convinced that it is the freely imaginative mind that is at the core of all vital music making and music listening… An imaginative mind is essential to the creation of art in any medium, but it is even more essential in music precisely because music provides the broadest possible vista for the imagination since it is the freest, the most abstract, the least fettered of all the arts: no story content, no pictorial representation, no regularity of meter, no strict limitation of frame need hamper the intuitive functioning of the imaginative mind.