Aware that a cynic who has not experienced such cultures would readily accuse her of “a tiresome outburst of romanticism,” she considers the deeper paradoxes such contrasts expose. In a passage evocative of Denise Levertov’s sublime poem “Sojourns in the Parallel World,” she writes:

Complement with Dylan Thomas’s short, stunning poem “Being But Men” and the great nature writer Loren Eiseley on reclaiming our sense of the miraculous in a mechanical age, then revisit the beloved Trappist monk Thomas Merton’s fan letter to Rachel Carson about wisdom in the age of technology and Nick Cave on transcendence in the age of algorithms.

A generation after the trailblazing cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict insisted that “there is no reason to suppose that any one culture has seized upon an eternal sanity and will stand in history as a solitary solution of the human problem,” heralding instead “the great diversity of social solutions” that different cultures have devised for the same common human problems — love and death, beauty and terror, the daily puzzle of being — Dervla Murphy (November 28, 1931–May 22, 2022) set out to see them for herself by going halfway around the world on a bicycle, with little more than a passport, map, two pens, and Blake’s poems in her sole saddlebag. (If you don’t yet know of this remarkable woman — that is, if you haven’t yet fallen hopelessly in love with her — read this first.)

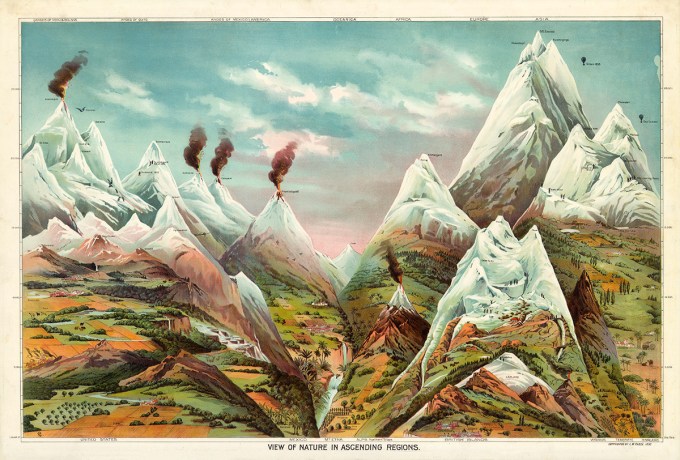

I suppose all our scientific advances are a wonderful boost for the superior intellect of the human race but what those advances are doing to us seems to me quite literally tragic. After all, only a handful of people are concerned in the excitement and stimulation of discovering and developing, while millions lead feebler and more synthetic lives because of the achievements of that handful.

People now use less than half their potential forces because “Progress” has deprived them of the incentive to live fully. All this has been brought to the surface of my mind by the general attitude to my conception of travelling, which I once took for granted as normal behaviour but which strikes most people as wild eccentricity, merely because it involves a certain amount of what is now regarded as hardship but was to all our ancestors a feature of everyday life — using physical energy to get from point A to point B. I don’t know what the end result of all this “progress” will be — something pretty dire, I should think. We remain part of Nature, however startling our scientific advances, and the more successfully we forget or ignore this fact, the less we can be proud of being men*.

With an eye to the tragic hijacking of pure science — that wonder-smitten human impulse to befriend the most elemental strata of reality — for purposes of power, economic advancement, and personal gain, she adds:

An unlikely antidote to the double-edged sword of what we call “progress” — a sword that goes on razing us of some of our tenderest humanity and most vibrant capacity for aliveness — is to be found in travel, in the willingness for full-bodied engagement with the variousness of the world, which demands of us both our highest humanity and our animal nature: