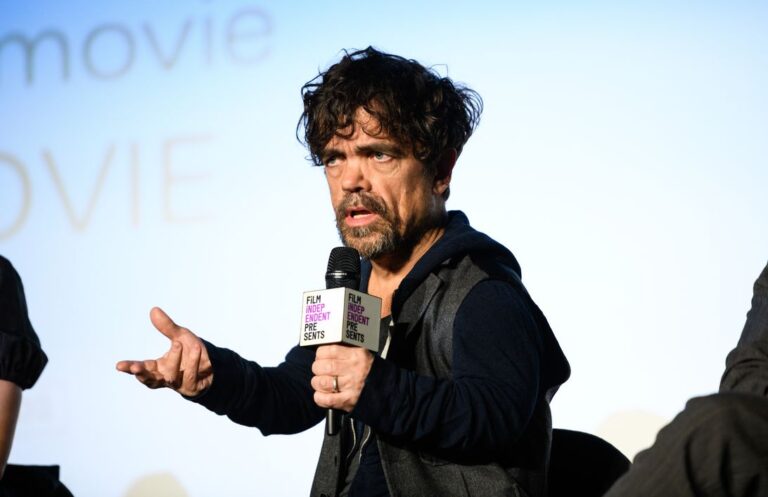

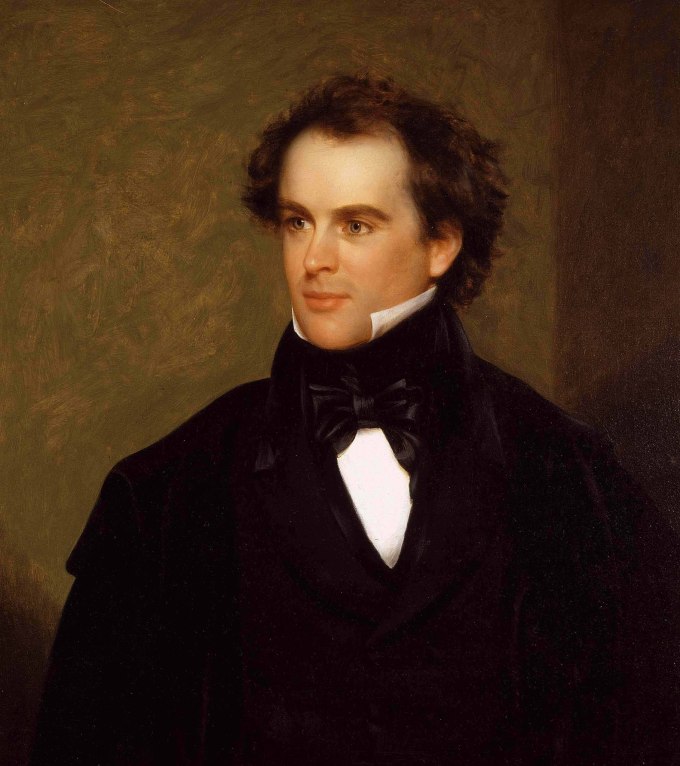

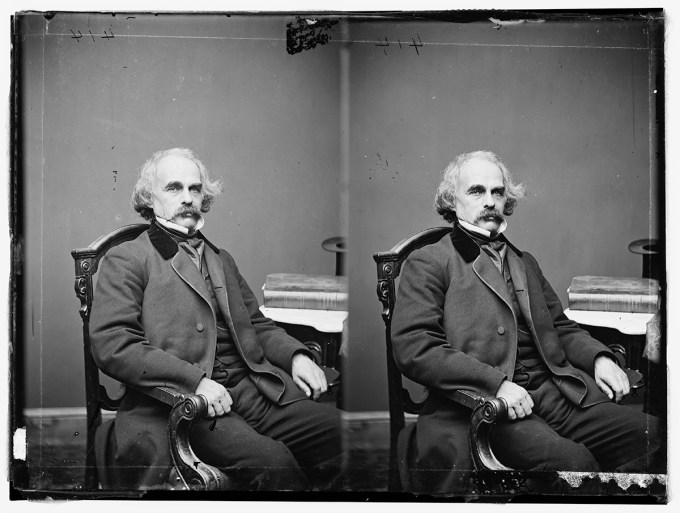

Published the year of Darwin’s bittersweet reckoning with his own daughter’s mortality and sold by private subscription a century and a half before Patreon, The Scarlet Letter raised 0 for Hawthorne and his family, which helped them leave the sadnesses of Salem, sadnesses that had haunted him long before his season of losses — so much so that he had added the “w” in his surname to sever the association with his ancestor John Hathorne, the leading judge in the Salem witch trial.

It is said that Orlando, inspired by the passionate real-life love Virginia Woolf shared with Vita Sackville-West, is “the longest and most charming love letter in literature” — said by Vita’s own son. But the most charming love letter in literature might be quite shorter and older and inspired by a very different kind of love — the purest, tenderest love of a parent for their young child.

Una’s “real soul,” her father observes, is one of uncommon complementarity, in which all the polar potentialities of human nature coexist and are harmonized:

With the income from The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne moved the family to a small red house in the Berkshires. It was there that Herman Melville fell in love with him, dedicating Moby-Dick to Hawthorne.

Years after her father’s death, Una recovered his final manuscript — the unfinished novel Septimius Felton; or, the Elixir of Life — and, with the help of her friend Robert Browning, had it published in serial form in The Atlantic Monthly. She died five years later, at the age her mother had married her father, returning far too young to the supra-human mystery her father had always perceived in her — the mystery the sole possible meaning and redemption of which he had contoured long ago, when he and Una were both alive and his mother was no more. In the notebook entry recounting that darkest hour of his life at his mother’s deathbed in the high summer of 1849, he had written:

Baby Una, named for the beautiful and fierce young daughter of the dragon-imprisoned king and queen in the 1590 English epic poem The Faerie Queene, instantly filled Hawthorne with “a very sober and serious kind of happiness that springs from the birth of a child.” Una would later become the model for the heroine’s daughter in The Scarlet Letter — the 1850 novel that lifted Hawthorne out of poverty, abruptly ending his “many good years” as “the obscurest man of letters in America,” per his own recollection, to render him one of his country’s most celebrated artists.

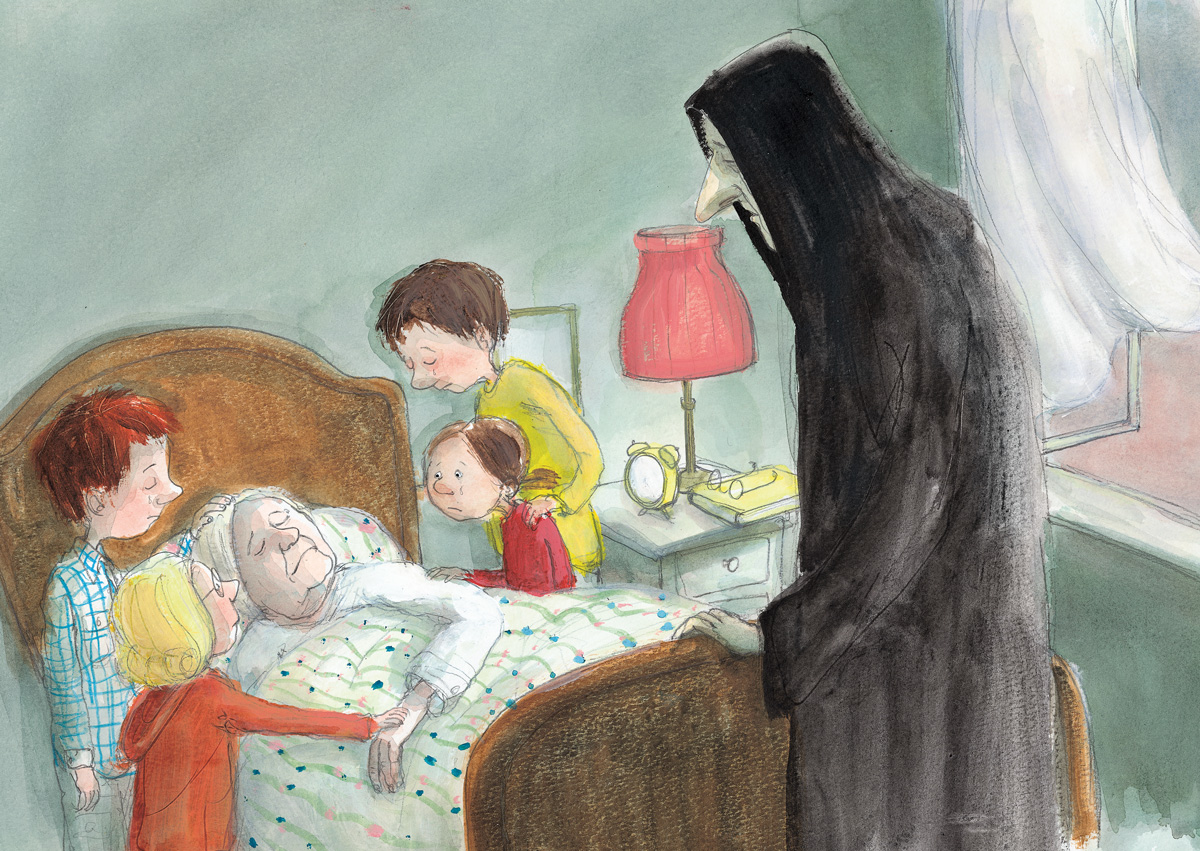

Una’s almost otherworldly syncopation of reason and emotion, of sympathy and stoicism, comes alive most vividly in a midsummer notebook entry Hawthorne penned while his mother was fast approaching “the drift called the infinite.”

Finding himself the strange fulcrum of the seesaw between life and death, Hawthorne observes his small daughter take a lively, compassionate interest in his dying mother’s suffering, begging to be let into the bedchamber to be at her grandmother’s side, role-playing convalescent and caretaker with her little brother. Hawthorne writes:

For a long time I knelt there, holding her hand… Afterwards I stood by the open window and looked through the crevice of the curtain. The shouts, laughter, and cries of the two children had come up into the chamber from the open air, making a strange contrast with the death-bed scene. And now, through the crevice of the curtain, I saw my little Una of the golden locks, looking very beautiful, and so full of spirit and life that she was life itself. And then I looked at my poor dying mother, and seemed to see the whole of human existence at once, standing in the dusty midst of it. Oh, what a mockery, if what I saw were all, — let the interval between extreme youth and dying age be filled up with what happiness it might!

I know not what she supposes to be the final result to which grandmamma is approaching… There is something that almost frightens me about the child, — I know not whether elfish or angelic, but, at all events, supernatural. She steps so boldly into the midst of everything, shrinks from nothing, has such a comprehension of everything, seems at times to have but little delicacy, and anon shows that she possesses the finest essence of it, — now so hard, now so tender; now so perfectly unreasonable, soon again so wise. In short, I now and then catch an aspect of her in which I cannot believe her to be my own human child, but a spirit strangely mingled with good and evil, haunting the house where I dwell.

The next day — forty-five years and twenty-seven days after she had given birth to him — his mother died, with Hawthorne and his sisters at her side. The loss savaged him with grief. Sophia recounted that she saw him, this quiet monolith of composure, come “near a brain fever.” But Hawthorne was his daughter’s father, his own seemingly unfeeling exterior armoring a tender and sensitive soul — perhaps that is why this duality so frightened him in Una. (Children, after all — like anyone we love — are mirrors for understanding ourselves, disquieting us most when they reflect what we most fear or struggle to comprehend in ourselves.)

Four years before that overnight success a lifetime in the making, when Una turned two and a second child was about to join the family, Hawthorne took a day-job as surveyor for the Customs House in Salem. There he toiled for three years, at the near-total expense of his writing. During that creatively deadening period, his love for his children sustained him, fed his famished artistic soul, reawakened him to life. He recorded these tender, vitalizing observations of the children’s daily doings and unfurling beings in a family notebook he shared with Sophia, posthumously included in the affectionate biography Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife (public library) by their second child, Una’s brother Julian.

When their first child — a daughter — was born in 1844, Hawthorne was a struggling writer about to turn forty. Seven years earlier, his first book — Twice-Told Tales, a retelling of classic anonymous stories — had hardly gotten into the hands of readers when the Panic of 1837 smote the young country as its first Great Depression. And so the young author had hardly made his name even among the most literary of his contemporaries — what Longfellow lauded as a “sweet, sweet book” had left the highly informed and discerning Margaret Fuller impressed, but with the impression that it was written by “somebody in Salem” assumed to be a woman.

I found the tears slowly gathering in my eyes. I tried to keep them down, but it would not be; I kept filling up, till, for a few moments, I shook with sobs… Surely it is the darkest hour I ever lived.

As soon as everyone else left the room, the armor came undone:

This latter insight, far predating the dawn of psychology as we know it, touches the eternal depths of human nature — as adults, we are always at our most childish when we allow the ceaselessly shifting weather systems of our moods to override our moral precepts, thrusting us back in time to those primal impulses of reflexive reaction, cutting us off from the capacity for reflective response that is the mark of maturity.

The sentiment of a picture, tale, or poem is seldom lost upon her; and when her feelings are thus interested, she will not hear to have them interfered with by any ludicrous remark or other discordance. Yet she has, often, a rhinoceros-armor against sentiment or tenderness; you would think she were marble or adamant. It seems to me that, like many sensitive people, her sensibilities are more readily awakened by fiction than realities.

Ten days after his mother’s death, Hawthorne was bluntly fired from his job at the Customs House when the new Whig administration took office. He began writing The Scarlet Letter that day, completing it with the same astonishing rapidity — six months — that John Steinbeck, who also worked a series of soul-hollowing jobs, would complete The Grapes of Wrath a century later.

Fatherless since the age of four, achingly introverted, a man of “great, genial, comprehending silences” considered “handsomer than Lord Byron,” known to duck behind trees and rocks to avoid speaking with townspeople, Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804–May 19, 1864) was an old bachelor of thirty-eight when he married Sophia Peabody — an intellectually voracious and artistically gifted old maid of thirty-three, a linchpin figure in Figuring, and sister to the titanic visionary Elizabeth Peabody, who had coined the term Transcendentalism.

Her beauty is the most flitting, transitory, most uncertain and unaccountable affair, that ever had a real existence; it beams out when nobody expects it; it has mysteriously passed away when you think yourself sure of it. If you glance sideways at her, you perhaps think it is illuminating her face, but, turning full round to enjoy it, it is gone again. When really visible, it is rare and precious as the vision of an angel. It is a transfiguration, — a grace, delicacy, or ethereal fineness, — which at once, in my secret soul, makes me give up all severe opinions that I may have begun to form about her. It is but fair to conclude that on these occasions we see her real soul. When she seems less lovely, we merely see something external. But, in truth, one manifestation belongs to her as much as another; for, before the establishment of principles, what is character but the series and succession of moods?

In the bleak midwinter of 1849, five weeks before Una’s fifth birthday, Hawthorne writes in the notebook: