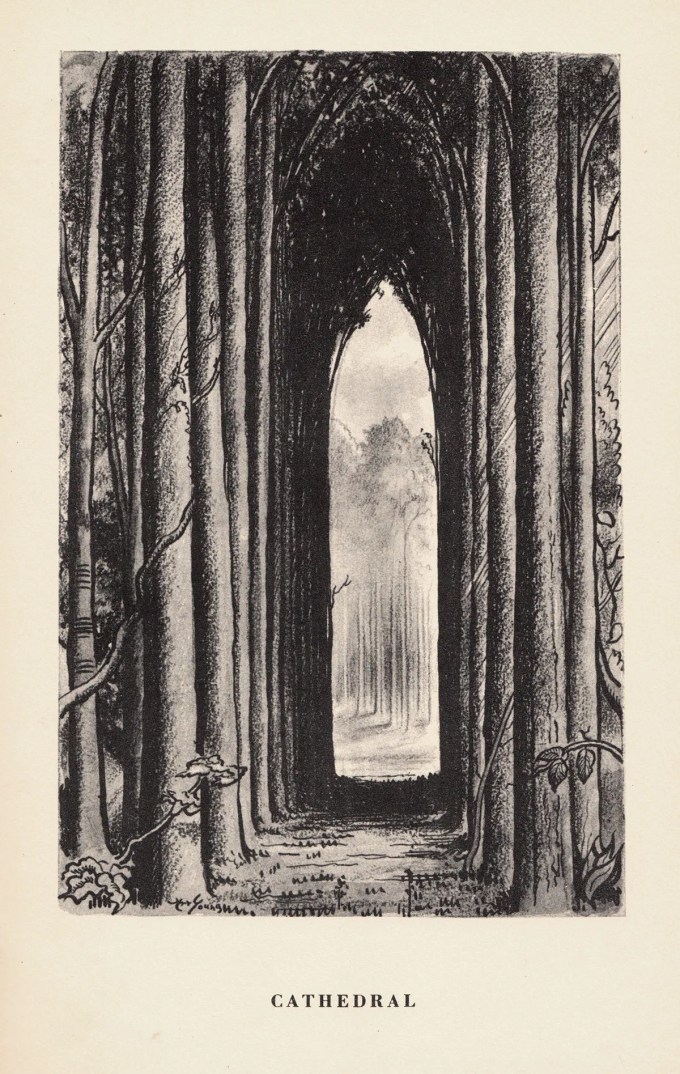

The forest, this place of constant change that feels somehow atemporal, an everlasting Yes! to life echoed by an ungrudging and vibrant Yes! to death — a place where one feels most intimately the elemental yet counterintuitive fact that death is not the assailant of life but the ultimate consecration of its lucky possibility.

The forest, with its colossal trees that have been part-dead since their saplinghood centuries ago and are at the same time potentially immortal.

This might be why we see ourselves so readily in trees, why we find in them our greatest lessons and the deepest truths about love.

I have been thinking about growth and decay while walking long bundled hours in an old-growth forest.

Rootless and restless and warmblooded, we

blaze in the flare that blinds us to that slow,

tall, fraternal fire of life as strong

now as in the seedling two centuries ago.

Very slowly burning, the big forest tree

stands in the slight hollow of the snow

melted around it by the mild, long

heat of its being and its will to be

root, trunk, branch, leaf, and know

earth dark, sun light, wind touch, bird song.

Whitman, whose atoms now belong to some mycelial wonder pushing up the leaves of cemetery grass and nourishing the roots of the two towering trees that stand sentinel on either side of his tomb, trees that were saplings when he laughed out of life.

Complement with Amanda’s reading “When I Am Among the Trees” by Mary Oliver and poet Jane Hirshfield reading “Today, Another Universe” — her kindred take on the life and death of a single tree — then revisit Le Guin on anger, the magic of real human conversation, the meaning of loyalty, getting to the other side of suffering, and her timeless “Hymn to Time.”

Whitman, who two centuries ago declared himself to “know the amplitude of time” and “laugh at what you call dissolution.”

The forest, with its ceaseless syncopation of generation and decomposition that composes the pulse-beat of total aliveness.

I have been thinking a great deal about growth — what it means, what it asks of us, how it feels when unforced but organic. I have been thinking about growth and decay, the interplay between the two, the way all growth requires regeneration, which in turn requires a shedding, a composting, a reconstituting of old material. We don’t always know what needs to be shed, or what the optimal direction of growth is. This is where the “blind optimism” of a tree is helpful — there is consolation in trusting the quiet workings of chemistry and the primal instinct for orienting to the light.

KINSHIP

by Ursula K. Le Guin

While thinking about life and death and poetry in an old-growth forest, I thought of this immortal line: “The word for world is forest” — the title of a novella by Ursula K. Le Guin (October 21, 1929–January 22, 2018). I thought of the short, stunning tree-poem she wrote at the end of her life, originally published on the pages of Orion Magazine and recently included, fittingly, in Old Growth — their splendid anthology of sylvan literature from the magazine’s decades-deep archive. Here it is, brought tenderly to life by my tree-loving, poetry-loving, life-and-death-loving friend and kindred spirit Amanda Palmer, to which I have added the perfect sonic companionship of an old recording of Bach’s Organ Concerto in D Minor.

Walt Whitman saw in them models for the highest measure of authenticity and why he, in consequence, celebrated the friend he most loved as “true, honest; beautiful as a tree is tall, leafy, rich, full, free… [she] is a tree.”