We see Olenka’s mode of loving, from one angle, as a beautiful thing: in that mode, the self disappears and all that remains is affectionate, altruistic regard for the beloved. From another angle, we see it as a terrible thing, the undiscriminating application of her one-note form of love robbing love of its particularity: Olenka, love dullard, vampirically feeding upon whomever she designates as her beloved.

Maybe you won’t.

Chekhov answers: “Yes.”

The great difficulty, too, is how easily those life-expanding Yeses that can open larger vistas of possibility come fear-concealed as Nos, or how those life-preserving Nos that keep us from entering into experiences too damaging or too small for us bear the momentum of pre-conditioned Yeses. And so we project who we are and what we need onto those we love, and find in them reflections of who we long to be or fear we might be, swarming them and swarming ourselves in all the blooming buzzing confusion of our unmet needs.

While it is true, as generations of psychologists have found, that “who we are and who we become depends, in part, on whom we love” — a process known as limbic revision — it is also true, as generations of self-aware humans have found, that whom we love depends in large part on who we already are. Our original wounds, our formative attachments, our patterned longings all shape how we engage with those we have chosen to love, to the extent that we are choosing them at all. “People can’t, unhappily, invent their mooring posts, their lovers and their friends, anymore than they can invent their parents,” James Baldwin astutely observed in contemplating the paradox of freedom. “Life gives these and also takes them away and the great difficulty is to say Yes to life.”

We see this mode of loving as powerful, single-pointed, pure, answering all questions with its unwavering generosity. We see it as weak: her true, autonomous self is nowhere to be found as she molds herself into the image of whatever male happens to be near her (unless he’s a cat).

Because don’t we all do some version of this, when in love? When your lover dies or leaves you, there you are, still yourself, with your particular way of loving. And there is the world, still full of people to love.

The story seems to be asking, “Is this trait of hers good or bad?”

The story, like every great work of fiction, becomes a mirror for reflection on the most intimate realities of life. Saunders writes:

This puts us in an interesting state of mind. We don’t exactly know what to think of Olenka. Or, feeling so multiply about her, we don’t know how to judge her.

The great peril and great possibility of every love is that this third partner can be a rewounder masquerading as a healer, and equally a healer in disguise, masked beyond recognition by our own patterned way of seeing. So much of our suffering springs from this confusion and so much of our sanity is redeemed when at last we shed our own blinding masks and come to kneel at the fount of clarity.

This is not to demean and diminish love as a mere process of projection — Stendhal’s seven-stage delusion of crystallization and decrystallization — or a mere process of reflection — Ortega’s insightful but limited and limiting theory of what our lovers reveal about us — but to honor the elemental fact that each relationship is not between two people, but between three: the two partners, each with their pre-existing patterns of love and loss, and the third presence of the relationship itself — an intersubjective co-creation that becomes the third partner, endowed with the power to deepen those patters, or to change them.

We want to believe that love is singular and exclusive, and it unnerves us to think that it might actually be renewable and somewhat repetitive in its habits. Would your current partner ever call his or her new partner by the same pet name he/she uses for you, once you are dead and buried? Well, why not? There are only so many pet names. Why should that bother you? Well, because you believe it is you, in particular, who is loved (that is why dear Ed calls you “honey-bunny”), but no: love just is, and you happened to be in the path of it. When, dead and hovering above Ed, you hear him call that rat Beth, your former friend, “honey-bunny,” as she absentmindedly puts her traitorous finger into his belt loop, you, in spirit form, are going to think somewhat less of Ed, and of Beth, and maybe of love itself. Or will you?

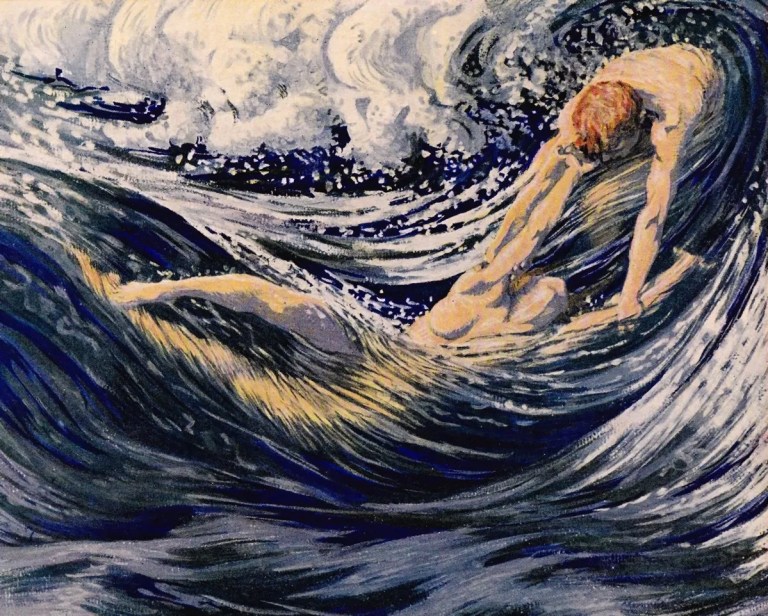

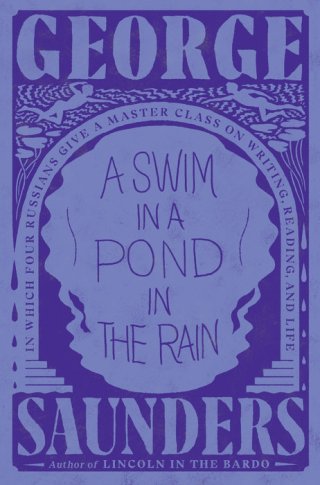

That is what George Saunders explores in his immensely insightful and sensitive annotated reading of Chekhov’s short story “The Darling” — one of the seven classic Russian short stories he examines as “seven fastidiously constructed scale models of the world” in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life (public library), using each as a portable laboratory for the key to great storytelling.

After a beautiful translation of “The Darling” — a story about a woman who loves four very different people the same patterned way, the only way she knows how, which has entirely to do with her learned understanding of love and nothing to do with its objects, and so she suffers greatly when each of these loves leaves her in the same lonely place; a story the essence of which Saunders captures perfectly as being “about a tendency, present in all of us, to misunderstand love as ‘complete absorption in,’ rather than ‘in full communication with’” — he pauses to marvel at Chekhov’s subtlety in challenging our reflex toward lazy binaries, his mastery in training our muscle of ambiguity, uncertainty, and nuance — which is, of course, the only we grasp and savor the full Yes of life. Saunders writes: