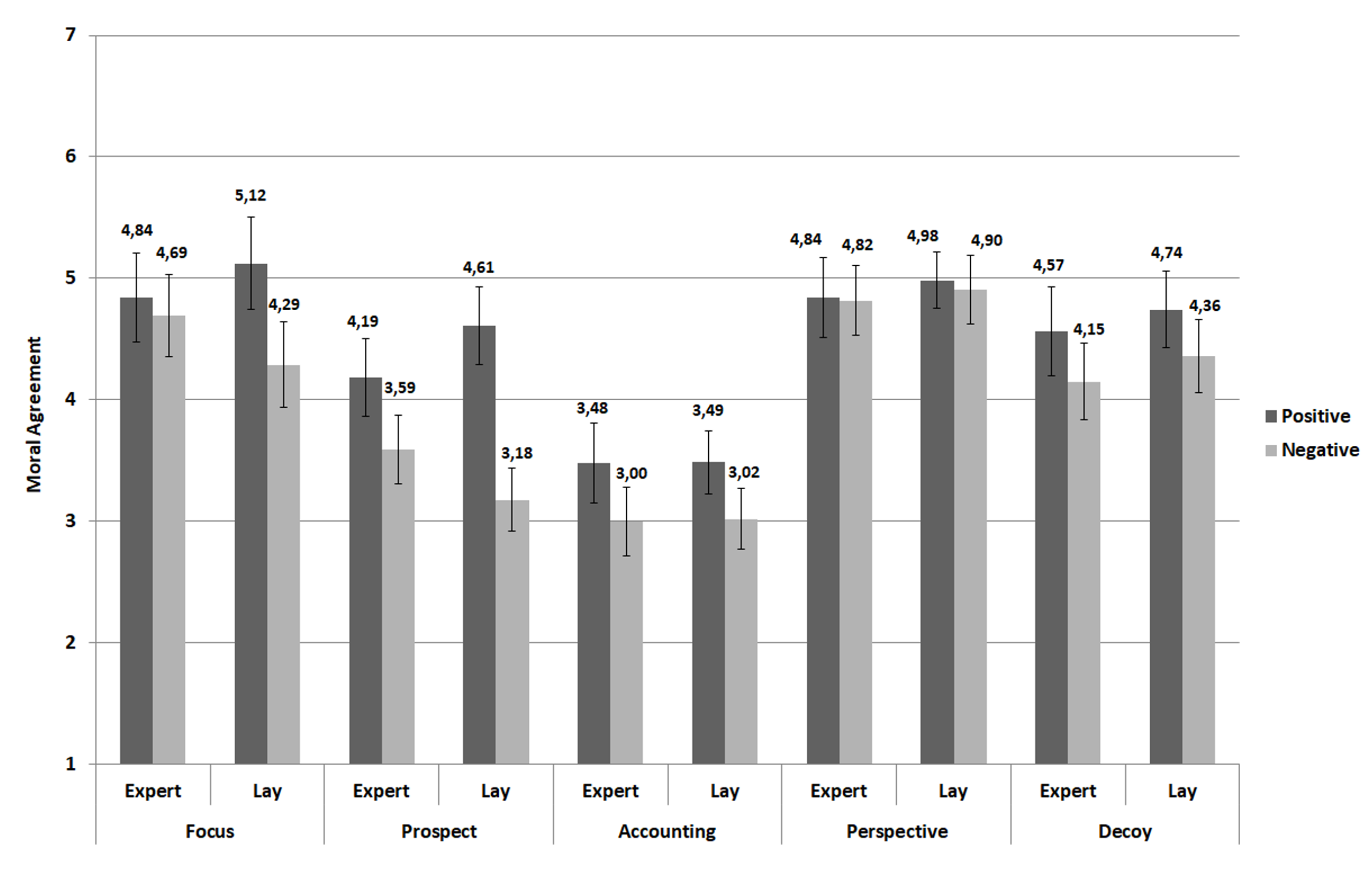

The most popular response to the x-phi challenge has been the expertise defense, which starts from the assumption that professional philosophers are experts in their areas of specialization—in analogy to other disciplines, like law or math. However, x-phi studies until the early 2010s had almost exclusively been done with philosophical laypeople—and not with trained philosophical experts. So, according to the expertise defense, the inductive leap from laypeople to philosophical experts is unwarranted, and the burden of proof for showing that philosophers’ intuitive judgments are equally problematic rests solely on experimental philosophers here. Across all scenarios, our manipulation had a significant effect on both moral philosophers and laypeople’s intuitive judgments. And while the size of the effect was descriptively larger for laypeople than for moral philosophers, this difference in effect-size was not statistically significant. Overall, the intuitive judgments of moral philosophers and laypeople were relatively close to each other—without any of the stark differences that one would expect in domains of genuine expertise, such as chess or math.

How much do you disagree or agree with the following claim:

Carl should make loud noises, which will result in [the five swimmers being saved / the fisherman being killed].

Intuitive Expertise in Moral Judgments

by Joachim Horvath & Alex Wiegmann

“People’s intuitive judgments about thought experiment cases are influenced by all kinds of irrelevant factors… [and] the issue of intuitive expertise in moral philosophy is anything but settled.”

So Joachim Horvath and Alex Wiegmann (Ruhr University Bochum) decided to find out more on how such irrelevant factors influence moral philosophers’ intuitions about various cases through a large online study. The results were recently published in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy, some of which they share in the following guest post.*

Since experimental philosophy (or x-phi) got started in the early 2000s, non-experimental philosophers have thought hard about how to resist the challenge that its experimental findings pose for the method of cases. As it seems, people’s intuitive judgments about thought experiment cases are influenced by all kinds of irrelevant factors, such as cultural background, order of presentation, or even innate personality traits—to such an extent that some experimental philosophers have declared them unreliable and the method of hypothetical cases unfit for philosophical purposes.

[art: Phlegm, “Mechanical Shark” mural]

However, since only a handful of effects have been tested with moral philosophers so far, the issue of intuitive expertise in moral philosophy is anything but settled. We therefore decided to broaden the scope of the investigated effects in a large online study with laypeople and expert moral philosophers. The basic idea of the study was to test five well-known biases of judgment and decision-making, such as framing of the question-focus, prospect framing, mental accounting, or the decoy effect, with a special eye on their replicability (see our paper for details). We then adapted these five effects to moral scenarios, for example, to a trolley-style scenario called Focus with a question framed in terms of people saved or people killed. Here is the text of Focus as we presented it to our participants (with the positive save-framing in bold):

Carl is standing on the pier and observes a shark swimming toward five swimmers. There is only one possibility to avoid the death of the five swimmers: Carl could make loud noises, and thereby divert the shark into his direction. However, there is a fisherman swimming on the path between Carl and the shark. Diverting the shark would therefore save the five swimmers but kill the fisherman.

What are the take-home lessons of our study? First, as in previous studies, expert moral philosophers are not immune to problematic effects, such as prospect framing, which adds to the growing evidence that tends to undermine the expertise defense. Second, unlike in previous studies, moral philosophers do enjoy a genuine advantage in some of the cases, most notably in the simple saving/killing framing of Focus, which was only (highly) significant in laypeople. We think that this is still cold comfort for proponents of the expertise defense, because one cannot predict from one’s armchair in which cases moral philosophers are just as biased as laypeople, and where they enjoy a genuine advantage. At best, our findings suggest the possibility of an empirical and more piecemeal version of the expertise defense. With sufficient experimental data, one might eventually be in a position to claim that moral philosophers’ intuitive judgments are better than those of laypeople with respect to this or that irrelevant factor under circumstances XYZ. How satisfying this would be for the metaphilosophical ambitions behind the expertise defense—and whether this would still deserve to be called “expertise”—is another matter.

But it was clear from the start that the expertise defense might just be a way to buy non-experimental philosophers some time, maybe for thinking about a better defense. For, it is relatively easy to test the same irrelevant factors with philosophical experts that already caused trouble in laypeople. This is what happened in a pioneering study by Schwitzgebel & Cushman, who found that moral philosophers are equally influenced by order effects with well-known ethical cases, such as trolley scenarios or moral luck cases—even when controlling for reflection, self-reported expertise, or familiarity with the tested cases. These findings have been confirmed since then, and new ones, such as the influence of irrelevant options, have been added.

In our preregistered experiment, moral philosophers and laypeople were randomly assigned to one of two conditions of framing direction (Positive or Negative), and presented with five moral scenarios that implemented the five different framing effects (Focus, Prospect, Accounting, Perspective, and Decoy—always in this order). The framing of the scenarios was expected to either increase (in the Positive condition) or decrease (in the Negative condition) agreement-ratings for the presented moral claims. The main results are displayed in the following figure:

Concerning individual scenarios, we found the biggest framing effect for the most well-known scenario: Tversky and Kahneman’s prospect framing (aka “Asian disease” cases). Applying a strict criterion (p < .05, two-sided), Prospect was the only individual scenario with a significant effect in moral philosophers, while laypeople were also significantly influenced by the simple saving/killing framing in Focus. With a weaker criterion (p < .05, one-sided), laypeople’s intuitive judgments would come out as biased in four out of five scenarios (with the exception of Perspective), and those of moral philosophers in three scenarios (Prospect, Accounting, and Decoy). The outlier in terms of non-significance was Perspective, which tested an alleged finding of “actor-observer bias” in professional philosophers and laypeople. Our high-powered study suggests, however, that this is probably a non-effect in both groups (in line with another failed replication reported here).