She writes:

In improvisation, the generation of material is spontaneous, but it’s never random. This in itself constitutes a paradox: If you can choose to play anything, with equal probability, what could make you choose any one thing — on the spur of the moment, blindly, trusting, without thinking about it — except chance? In other words, how can the spontaneous be anything but random; how can music made in a jolt of instinct, on a bolt out of the now, be endowed with a form that makes sense in time, as though it had been written and rewritten and practiced and memorized beforehand? And how, in making that first, most instinctive, most desperate decision, do we choose — if it really can be called “choosing,” if we really choose at all?

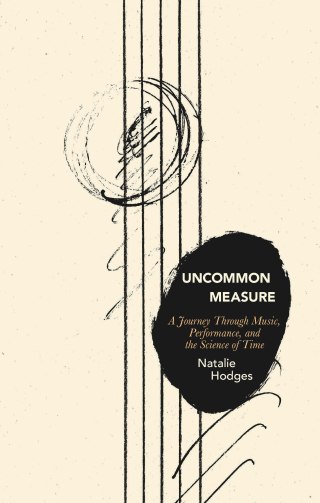

With an eye to Saint Augustine’s long-ago meditations on the secret chambers of memory, Hodges reflects:

[embedded content]

What shines through these fractures in the conscious self is a different sort of memory — not the conscious kind for which the DMN is ordinarily responsible, tasked with recalling the past and anticipating the future, but a mental process that is both unconscious and conscious of itself, self-referential for the duration of the improvisation, a kind of time-out-of-time that, on the miniature timescale of the improvisational period, seems to remember the future: The researchers found that while Montero was improvising on the piano, her musical stream of consciousness remained “structured and cohesive,” referencing patterns and building on motifs that had poured out of her unconscious mind earlier in the timeline of the improvisation — patterns and motifs laid down in anticipation of their future reference.

For all this perplexity, there is something incredibly liberating in improvisation — a sort of “unselfing,” to borrow Iris Murdoch’s perennially lovely term; something that provides, as Hodges puts it, “the feeling of easy self-suspension that in the best moments can accompany deep focus, the way that when you have to throw yourself into a task it becomes almost a way to abandon the self, almost a relief to leave the self behind.”

For all this perplexity, there is something incredibly liberating in improvisation — a sort of “unselfing,” to borrow Iris Murdoch’s perennially lovely term; something that provides, as Hodges puts it, “the feeling of easy self-suspension that in the best moments can accompany deep focus, the way that when you have to throw yourself into a task it becomes almost a way to abandon the self, almost a relief to leave the self behind.”

The improvisation task in Montero’s trial, the researchers found, resulted in decreased connectivity between the regions of the DMN overall — a momentary fracturing of the self, a temporary dissolving of its margins consistent with Montero’s assertion that she “gets out of the way” when she improvises, that she loses herself in the present, that she turns on the tap and lets the music flow.

The implication is profound: Since consciousness is the experience of “existing with a body over time,” improvisation quite literally opens up a different mode of consciousness that bends the arrow of time and taunts the second law of thermodynamics. The researchers called it “a form of embodied creativity,” revealing the unconscious dialogue between the body and the mind whispered beneath the conscious mind’s narrative about what is happening, what has happened, and what will happen.She takes these questions to a Radcliffe lecture titled “What Choice Do I Have?” by the virtuosic Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero, who has stunned millions with her astonishing improvisations on musical prompts given to her by the audience. Out of a tiny seed handed by a stranger, a striking original composition comes abloom in real time, with no premeditation and no practice — a skill so natural to Montero yet so seemingly otherworldly that her brain became the subject of an fMRI study, the findings of which affirm physicist and jazz saxophonist Stephon Alexander’s insistence that “it is less about music being scientific and more about the universe being musical.”

Improvisation, in other words, is our built-in remix rotor of consciousness.