Echoing Rachel Carson’s poetic-scientific observation that because our origins of the Earth, “there is in us a deeply seated response to the natural universe, which is part of our humanity,” Lopez writes:

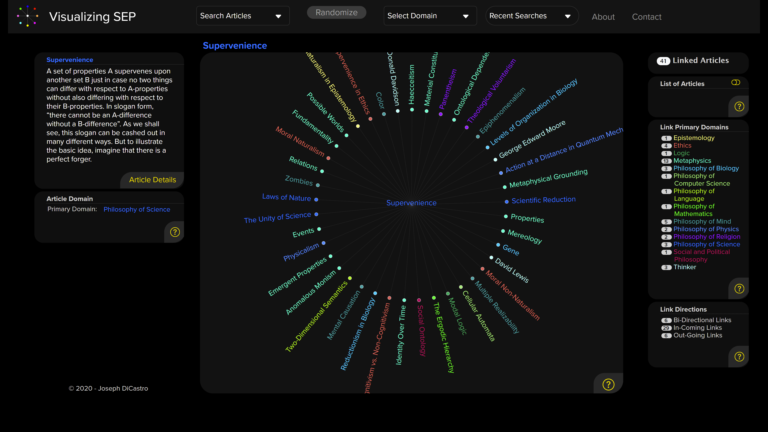

Complement with poet Jane Hirshfield on the power of metaphor, Nietzsche on its peril, and the story of how Newton propagated one of humanity’s most enduring metaphors, then revisit Giorgia Lupi and Stevanie Posavec’s poetic project Dear Data and Blaise Pascal on the art of persuasion.

For all their ravishing beauty, numbers remain abstractions cold and austere without a foothold of similitude in the living world, the world of touch and sight, of things and thingness. Seven has no meaning to the human mind without an object — we need to know seven what in order to fathom its sevenness. This may be why data, no matter their numerical grandeur, hold poor sway over the human soul; why metaphor, with its tangible tapestry of abstraction and concreteness, can move the mountain of the mind more powerfully than any human implement.

The goal in these conversations, from a traditional point of view, is to put off for a good while arriving at any conclusion, to continue to follow, instead, several avenues of approach until a door no one had initially seen suddenly opens. My own culture — I don’t mean to be overly critical here — tends to assume that while such conversations should remain respectful, the outcome must conform to what my culture considers “reality.”

With an eye to his many years of living, traveling, and working with native people, Lopez observes a distinct difference in styles of argument and persuasion — native cultures make more open-ended arguments that are not “trapped in literalness,” whereas industrialized societies default to logic and bulldoze with data. And yet, as human beings, we respond much more deeply to the former. Lopez writes of the older style of persuasion:

Reality, of course, is a tapestry of subjectivities and tacit consensuses, trapped often in the frames of reference laid down by any given life and always in the limitations of human consciousness, with its myriad blind spots for strata of reality we are physiologically and psychologically unequipped to perceive. It is only through metaphor that we can begin to conceive of what we cannot perceive, be it an atom or the black hole at the center of our galaxy or the pain of another.

I’ve felt for a long time that the great political questions of our time — about violent prejudice, global climate change, venal greed, fear of the Other — could be addressed in illuminating ways by considering models in the natural world. Some consider it unsophisticated to explore the nonhuman world for clues to solving human dilemmas, and wisdom’s oldest tool, metaphor, is often regarded with wariness, or even suspicion, in my culture. But abandoning metaphor entirely only paves the way to the rigidity of fundamentalism. To my way of thinking, to prefer to live a metaphorical life — that is, to think abstract problems through on several planes at the same time, to stay alert for symbolic and allegorical meanings, to appreciate the utility of nuance — as opposed to living a literal life, where most things mean in only one way, is the norm among traditional people like the Warlpiri.