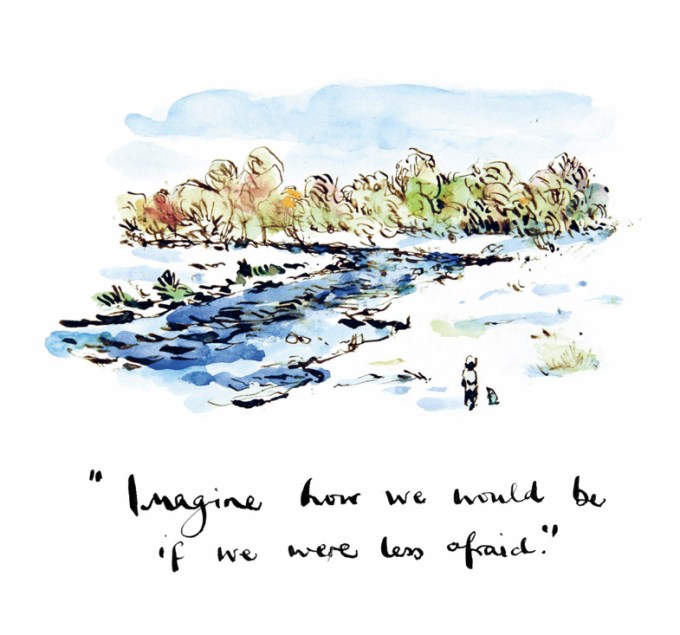

Leafing through it, I find myself thinking of the Stoic strategy for overcoming fear: “If you would not have a man flinch when the crisis comes,” Seneca wrote two millennia ago, “train him before it comes.” Better yet, this uncommon book intimates, train him before he becomes a man — train the child that becomes the man, the child that goes on living inside him, the eternal inner child for whom Maurice Sendak made all of his books, knowing that the highest achievement of adulthood is “having your child self intact and alive and something to be proud of.”

“What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?” the Proust Questionnaire asked David Bowie. “Living in fear.” Partway in time between Proust and Bowie, the young Hannah Arendt examined the eternal paradox of how to love and live with fear in her earliest published work, observing: “Fearlessness is what love seeks. Such fearlessness exists only in the complete calm that can no longer be shaken by events expected of the future… Hence the only valid tense is the present, the Now.”

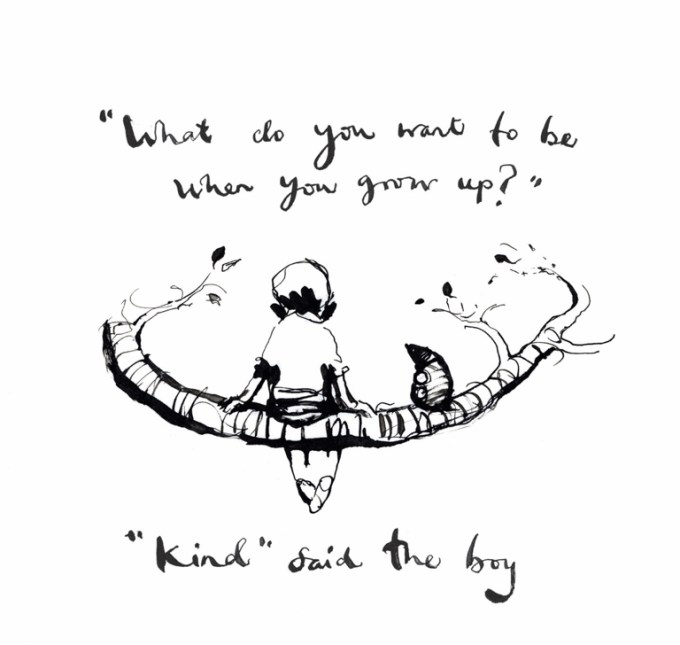

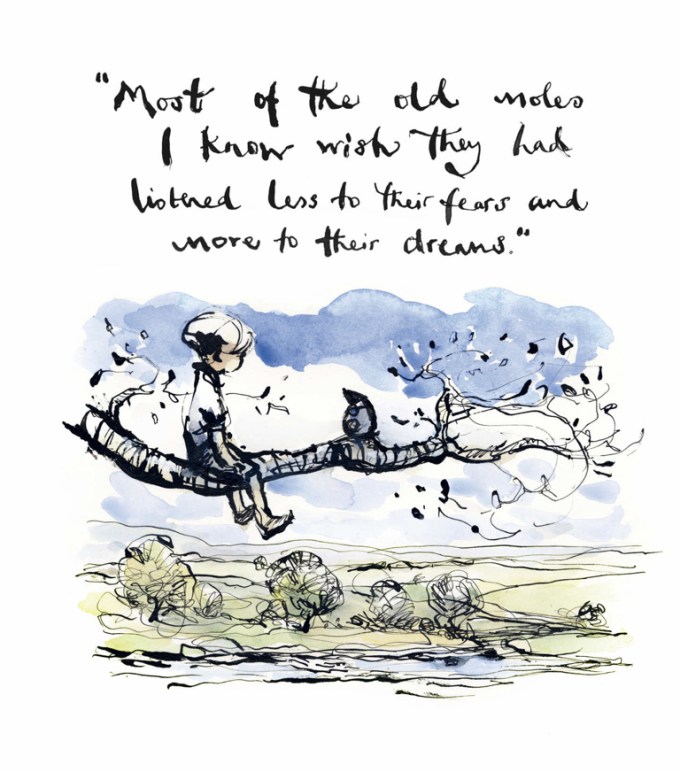

To a jaded grownup eye, this painted meditation might at times appear as the moral of a Zen parable or an Aesop fable, delivered without the storytelling and poetic rewards of the parable or fable — a little too obvious, a little too simplistic, a little too fortune cookie. But wherever it risks being trite, the story is saved by tenderness.

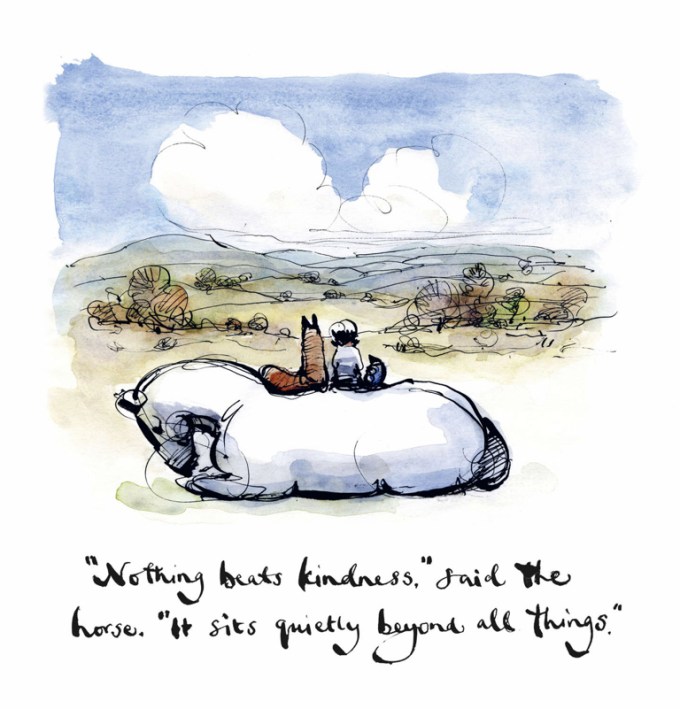

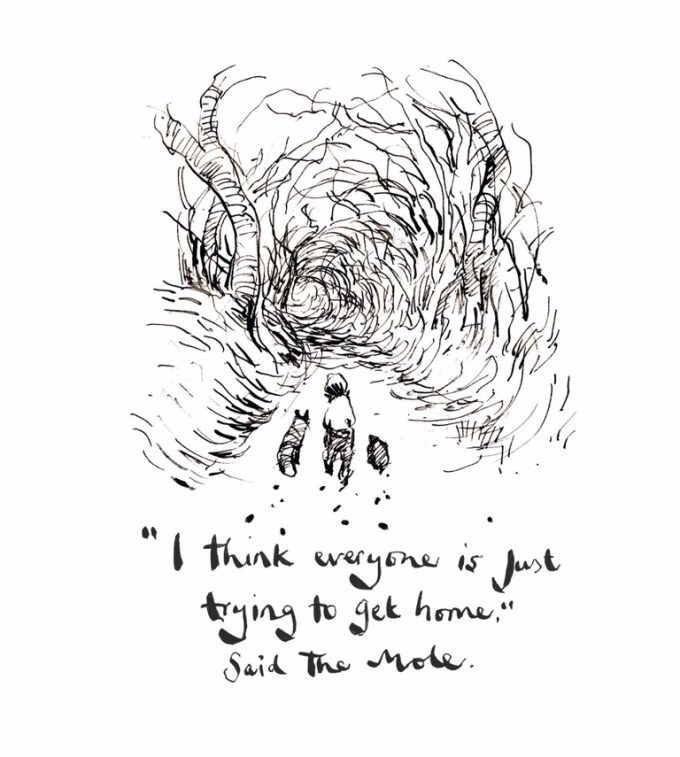

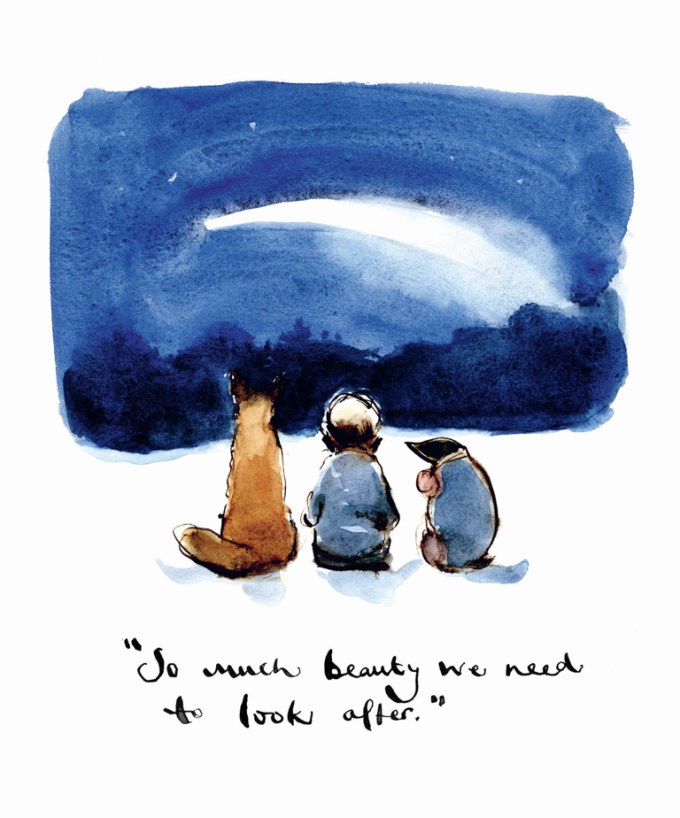

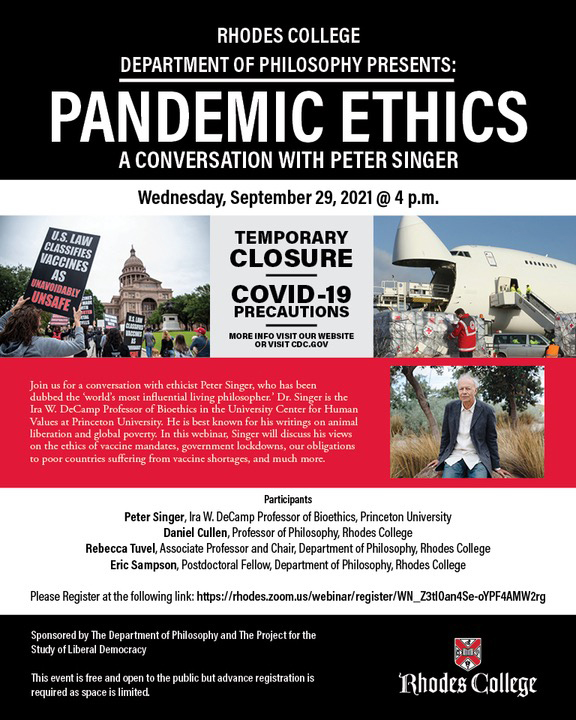

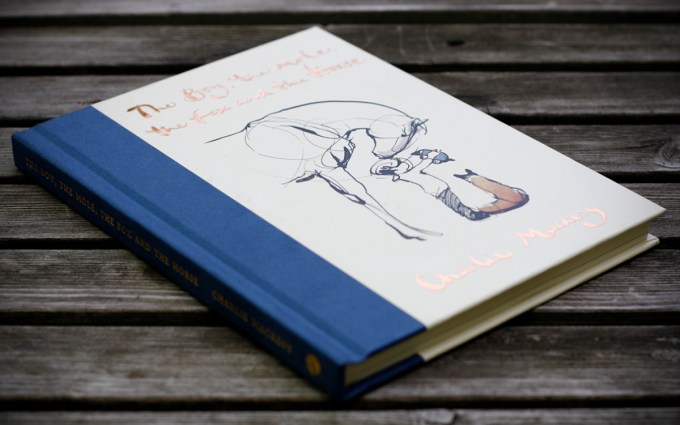

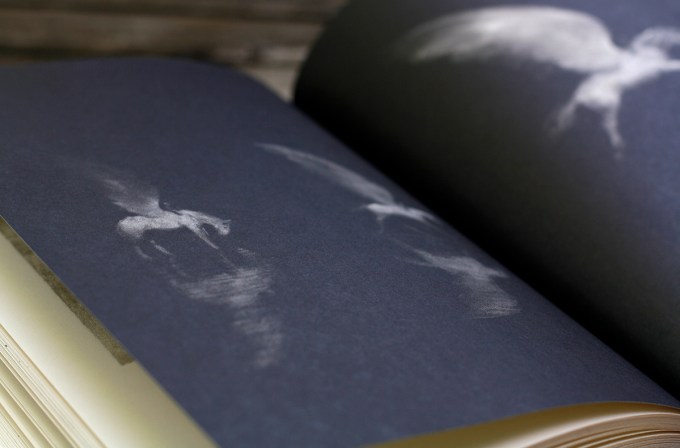

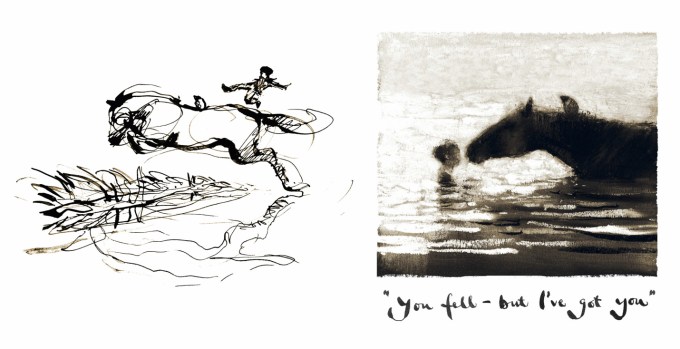

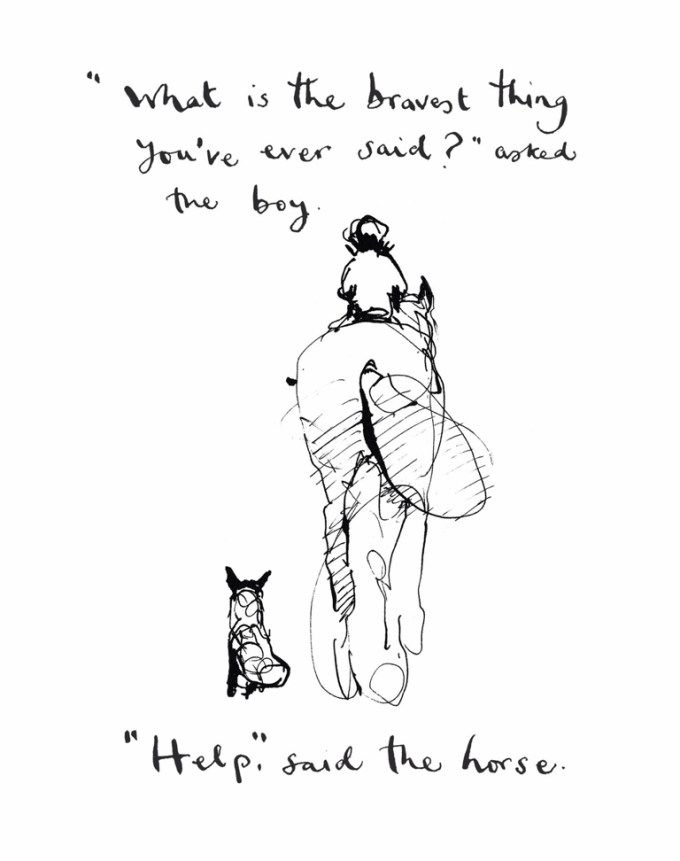

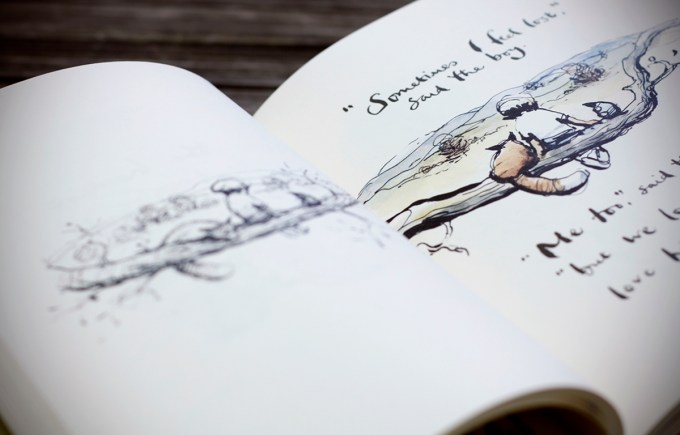

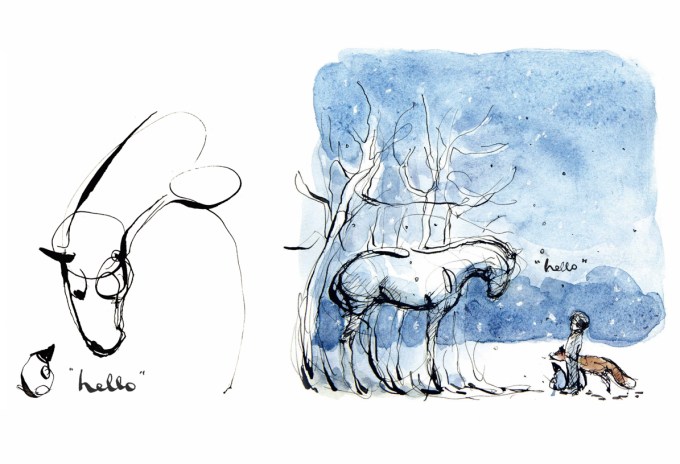

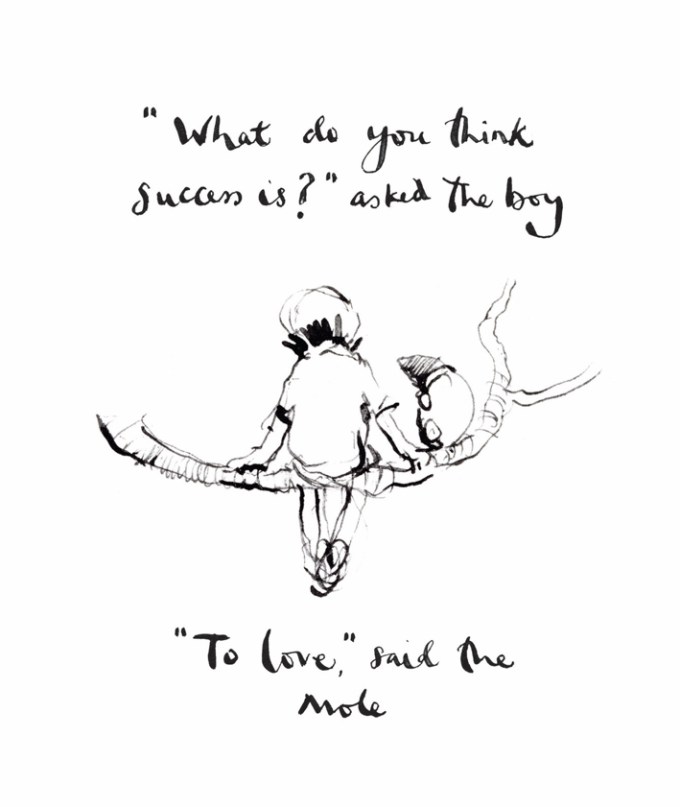

How to live not without fear but with it, how to let it be the foothold to our capacity for kindness and beauty, is what artist Charlie Mackesy explores in The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse (public library) — a serenade to life, in all its terrifying and transcendent uncertainty, sung in ink, watercolor, and wonder.

The book is less a story than a sensorium for meaning, rendered in spare words and soulful pictures. In a series of encounters and conversations with three other animals, each the keeper of a different kind of wisdom, a small boy confronts life’s big questions: how to live with fear, what it means to love and be loved, where to find the deepest and purest wellspring of fulfillment.

And yet a hallmark of our complex animal consciousness is our prospective imagination — the ability to tense into the future and everything that could possibly go wrong in it, aware that at any given moment we could be making the wrong choice, aware that even if there were a right one, and even if we had the wisdom to discern it and the will to make it, chance will always play a greater role than choice. This is the price we pay for the chance-miracle of being alive at all, each of us the improbable product of chance events that long prefigure our consciousness and its capacity for choice. (Just ask James Baldwin.) So we find ourselves here, cosmic castaways living with the perennial burden of figuring forward in an uncertain universe, discovering again and again in this burden the greatest blessings of beauty and meaning — the object of every theorem and the subject of every work of art, followed to its deepest source.

Complement The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse — many fragments of which Mackesy has made available as cards and prints — with poet Joseph Pintauro’s wondrous vintage picture-books for adults about life, love, mortality, and the wonder of uncertainty, then revisit the Nobel-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska on fairy tales and the importance of fear and beloved Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh on the four Buddhist mantras for turning fear into love.

In this regard, the book feels like a spiritual heir of Winnie the Pooh. And who, this side of 1943, can encounter a fox in a picture-book without thinking of The Little Prince?

There is an Odyssean quality to the path they travel together, but it is not that of the archetypal hero’s journey. At its heart is a celebration of friendship as life’s supreme collaborative heroism, which saves us from ourselves (the way anything that unselves us saves us).

It helps, too, to remember to take Mackesy’s hand and step into the perspective from which the story unfolds — that of a child wide-eyed with wonder, asking the simplest questions, which are also the deepest questions, with unselfconscious sincerity; it helps to remember Aldous Huxley’s admonition against our fear of sincerity as he contemplated the two types of truth all artists must reconcile, reminding us that while “not all obvious truths are great truths,” “all great truths are obvious truths.”