True belonging is the spiritual practice of believing in, and belonging to, yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn’t require that you change who you are. It requires that you be who you are.

Over the years, I have witnessed Debbie interview a kaleidoscope of visionaries — artists, writers, designers, scientists, musicians, philosophers, poets. Every time, guests leave the studio with that distinctive glow of feeling deeply understood and appreciated, a little bit more in touch with ourselves beyond our selves, reminded of who and what we are in the hull of our being, in that place from which we make everything we make as we go on making ourselves. In the nearly two decades since the birth of Design Matters — born in that primordial epoch before podcasts, when Debbie actually had to pay for the radio waves transmitting these conversations — she has interviewed more than 450 creative people about the arc of their lives. Roxane Gay — once her interview subject, now her wife — describes the resulting totality as “a gloriously interesting and ongoing conversation about what it means to live well, overcome trauma, face rejection, learn to love and be loved, and thrive both personally and professionally.”

But insecurity is, in some deeper sense, the opposite of vulnerability. V-Day founder and Vagina Monologues creator V looks back on her brush with death — which jolted her from a lifetime of trying to render herself invulnerable behind the armor of achievement and awakened her to a creaturely belonging with all of life — and reflects:

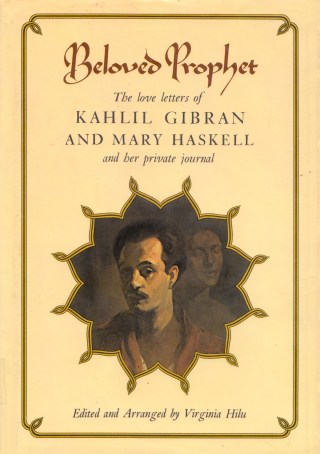

The best parts of the best interviews from this immense body of work are now gathered in Why Design Matters: Conversations with the World’s Most Creative People (public library). Pulsating through them are a handful of common themes — the elementary particles of which any creative life, any life of passion and purpose, any fully human life is built — none looming larger than the relationship between vulnerability and belonging, which constellates our entire cosmos of being: what we make, how we love, why we long for the things we long for, in love and in work.

The paradox of vulnerability, with its underlying longing for connection, comes most fully and ferociously alive in the sea of love. Alain de Botton, who has written about the subject with such uncommon sympathy and sensitivity over the arc of his own creative life, unravels the paradox in his conversation with Debbie:

One January afternoon several selves ago, I entered the corrugated black walls of a snug recording studio at the School of Visual Arts to sit at a microphone across from a woman dressed entirely and impeccably in black — a woman all stranger, all sunshine. I didn’t expect that, over the next hour, the warmth of her generous curiosity and her sensitive attention would melt away my ordinary reticence about discussing the life beneath the work. I didn’t expect that, over the next decade, we would become creative kindred spirits, then friends, then longtime romantic partners, and finally dear lifelong friends and frequent collaborators.

[…]

There beneath the surface waves of insecurity, in the deepest undercurrents of the soul, dwells our most elemental vulnerability. Brené Brown has made it her life’s work to dive into and study those depths. She tells Debbie:

Vulnerability at its heart is the willingness to show up and be seen when you can’t control perception.

With her usual sympathetic intellect, Brown captures the tender humanity beneath these maladaptive self-importances:

But a great interview does something else, too. A great touches the nucleus of being and potential, untouched by the forces of time and change.

But a great interview does something else, too. A great touches the nucleus of being and potential, untouched by the forces of time and change.

But a great interview does something else, too. A great touches the nucleus of being and potential, untouched by the forces of time and change.

I’m constantly tormented. I think that’s the nature of creating anything — that there’s something wrong with you if you don’t have doubts. There is the duality that you have tremendous insecurity and a tremendous drive.

But the dream is too often dampened by our sense that we are too imperfect for the total acceptance we imagine love to be. We instead turn to safer counterfeits of love that allow us to dream a perfect dream, channeling the paradox of vulnerability into the paradox of the crush. De Botton observes:

We try to control perception by simulating invulnerability from behind various masks and armors. Among most prevalent and pernicious in our culture is the broadcasting of busyness — this compulsion to signal that our valuable time is highly valued by others, that our presence and attention are in high demand, that how much we matter to the world exceeds the atoms of time at our disposal. (Autoresponders, particularly among creative people with no boss or client, are an especially unfortunate manifestation of this — rather than making the implicit and humane assumption that our response times are a natural function of their load and priorities, and therefore the best we can do no matter how long or short, an autoresponder makes a performative martyrdom of our own choices about how we are prioritizing our time and creative energies.)