Anne’s father died when she was eight. Immersed in music and art, with a gift for mathematics, she was only fifteen when she submitted her first poem to a magazine. With the notice of rejection came a friendly note of encouragement and praise from the editor, who eventually published a poem of hers two years later. Soon, her poems were populating prominent magazines, and newspapers frequently quoted verses from them.

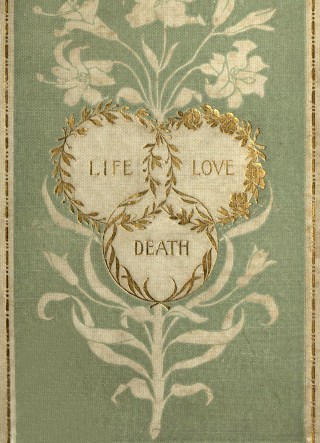

Her final poetry collection, aptly titled Songs about Love, Life, and Death (public library | public domain), was posthumously published by summer’s end. The Springfield Republican — the first paper to print Emily Dickinson’s poetry in her lifetime — lauded Aldrich as one of “the few who nearest share the moods of Sappho and her talents.” Seven years after her death, a major newspaper was still celebrating her “brief poems of unusual merit,” reprinting from them these “especially pregnant lines” — lines of abiding insight into how often we are the architects of our own suffering, a knowledge we carry with an uneasy awareness that only unmasons us more:

Complement with Simone Weil on how to make use of our suffering, Ursula K. Le Guin on getting to the other side of pain, and Sophie Scholl, who was even younger than Aldrich when she died for her values, on suffering, strength, and the deepest wellspring of courage, then revisit Dostoyevsky, just after his death sentence was repealed moments before his execution, on what makes life worth living.

She understood that personal suffering — pain on the scale of our individual lives — is the grandest portal to sympathy with universal life; she understood that “we bear a common pain” — the elemental pain that is the price of being alive, pain often invisible and always ineffable, except perhaps through art. She articulated this understanding with uncommon sympathy and splendor of sentiment in an 1890 letter to Emily Dickinson — herself a patron saint of suffering.

Those who read Anne Reeve Aldrich’s melancholy poetry speculated that she must be “an invalid” or “a sufferer,” but those who knew her knew a sunny-spirited young woman with a sense of humor and an exceptionally hopeful nature. Upon the posthumous publication of her final poems, she was compared to Elizabeth Barrett Browning — herself an emissary of radiance through inordinate suffering, who saw felicitous perseverance as a moral obligation. “Since Mrs. Browning has died, no sweeter spirit has breathed its life into verse than that of Anne Reeve Aldrich,” declared The Atlanta Constitution, noting how difficult it must be to die at the peak of one’s powers and prophesying that her poems would go on to “have a life of their own.” In them, she exalted not suffering itself but the full surrender to suffering, which triumph over it requires:

Rise to its fullest height,

Then watch a conquering anodyne

Softly assert its might.

Two millennia later, the young poet Anne Reeve Aldrich (April 25, 1866–June 28, 1892) attested to this insight with her life, short and soaring, spent writing soulful poems she considered “chiefly in a minor key” — the lyric epitome of “the bittersweet.”

I made the cross myself, whose weight

Was later laid on me.

This thought adds anguish as I toil

Up life’s steep Cavalry.

A life of patient suffering, such as I am sure yours must be, dear Miss Dickinson is a better poem in itself than we can any of us write, and I believe it is only through the gates of suffering, either mental or physical, that we can pass into that tender sympathy with the griefs of all of mankind which it ought to be the ideal of every soul to attain.

A year after the publication of her debut collection, The Rose of Flame, and Other Poems of Love (public library | public domain), the twenty-four-year-old Aldrich writes to the fifty-year-old Dickinson, whose own immense body of work never appeared as a book in her lifetime:

But midway through her twenties, the impartial hand of chance dealt her a rapidly debilitating illness. She lived through it with fierce devotion to life. Like Beethoven, who vowed to “take fate by the throat” when chance dealt him his own hand of suffering, Aldrich went on composing poems at a feverish pace until the very end, even as she grew too weak to write by hand. She dictated her last poem, “Death at Daybreak,” and died just before dawn on June 18, 1892 — a season after Whitman. She was twenty-six.