Cautioning against the common conflation of two distinct concepts — “solving the problem” and “correctly formulating the problem” — he observes:

It is a truism that the questions we ask shape the answers we find. It is, also, a truth. Another is that our questions — those wonderments, uncertainties, and quickenings of doubt that roil under the surface of life — are the atomic units of our creativity. Everything we make — our songs and our stories, our poems and our equations — we make to find out how the world works and what we are, to find out how to live with our restless longing for absolutes in a relative universe. Such questions — the questions that “can make or unmake a life,” in the words of the perceptive poet David Whyte — are both the raw material and the end result of all great art; art is tasked not with solving the puzzles of being but with dissolving the false certainties of our near-life experience.

I do sometimes preach heresies, but I have never, not once, gone so far as to deny that hard questions have no place in art. In conversations with my fellow writers, I always insist that it is not the job of the artist to solve narrowly specialized questions. It is bad for the artist to tackle what he* does not understand. We have specialists for dealing with specialized questions; it is their job to make decisions about the peasant commune, the fate of capitalism, the evils of alcoholism, about boots, and female complaints.

Complement with Polish poet Wisława Szymborska’s superb Nobel Prize acceptance speech about the creative power of uncertainty and David Whyte’s questioning poem “Sometimes,” then revisit Chekhov on the 8 qualities of cultured people and his 6 rules for a great story.

A century before James Baldwin observed that the task of the artist is to “drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides” and Susan Sontag insisted that the writer must guard against becoming an “opinion-machine,” Chekhov argues that the work of the artist is not problem-solving — this is best left to those with aptitude suited to the problem at hand — but question-framing:

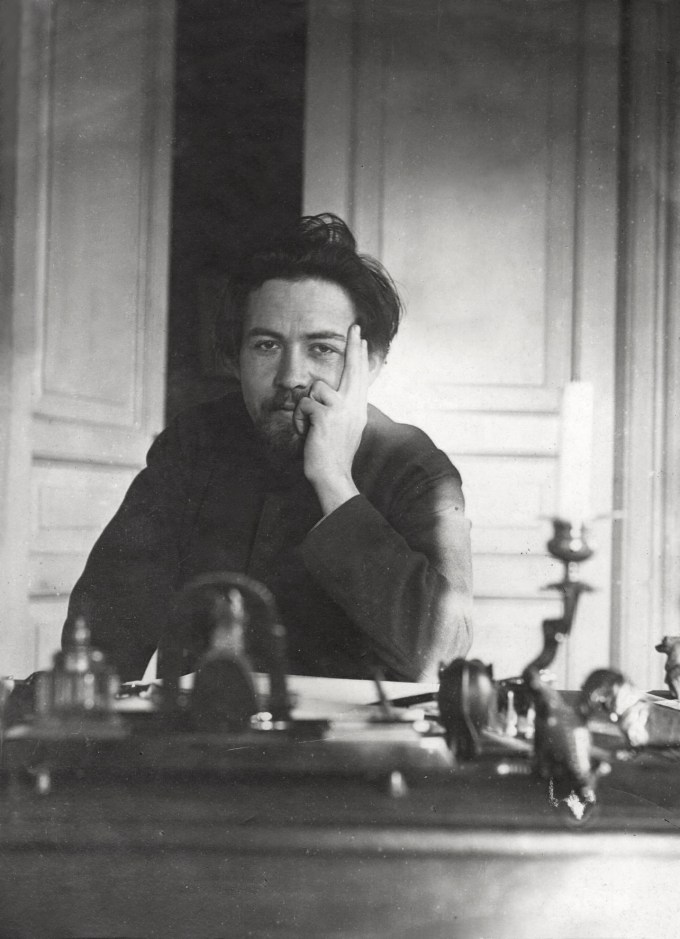

Corresponding with his friend Alexei Suvorin — a short story writer, playwright, and journalist, who went on to become the most influential newspaper publisher in the sunset hour of the Russian Empire — Chekhov, translated by Lena Lenček, writes on October 27, 1888:

Anton Chekhov (January 29, 1860–July 15, 1904) was twenty-eight when he addressed this in letter to a friend, included in How to Write Like Chekhov: Advice and Inspiration, Straight from His Own Letters and Work (public library).

Anyone who says that the artist’s sphere leaves no room for questions, but deals exclusively with answers, has never done any writing or done anything with imagery. The artist observes, selects, guesses, and arranges; every one of these operations presupposes a question at its outset. If he has not asked himself a question at the start, he has nothing to guess and nothing to select.

Only the latter is required of the artist. Not a single problem is resolved in Anna Karenina or Eugene Onegin, and yet the novels satisfy you completely because all the problems they raise are formulated correctly. It is the duty of the law courts to correctly formulate problems, but it is up to the members of the jury to solve them, each to his own taste.