It only takes one or two visionaries per generation to keep an idea alive, to sustain “sufficient interest” in something of quiet, unexampled promise. Generations after Herschel, Hobley’s cyanotypes live as a lovely antidote to photography’s fate in the age of smartphones and the visual culture of selfing — a fate Virginia Woolf anticipated a century ago, for she knew that it is the fate of every technology to be “killed by kindness”: to grow so easy and readily available as to become a cultural compulsion requiring no skill or sensibility. The art, of course, is never the technology and always its use as a means of meaning, of care, of delight. One can write a beautiful and layered letter that reads like a prose poem using email.

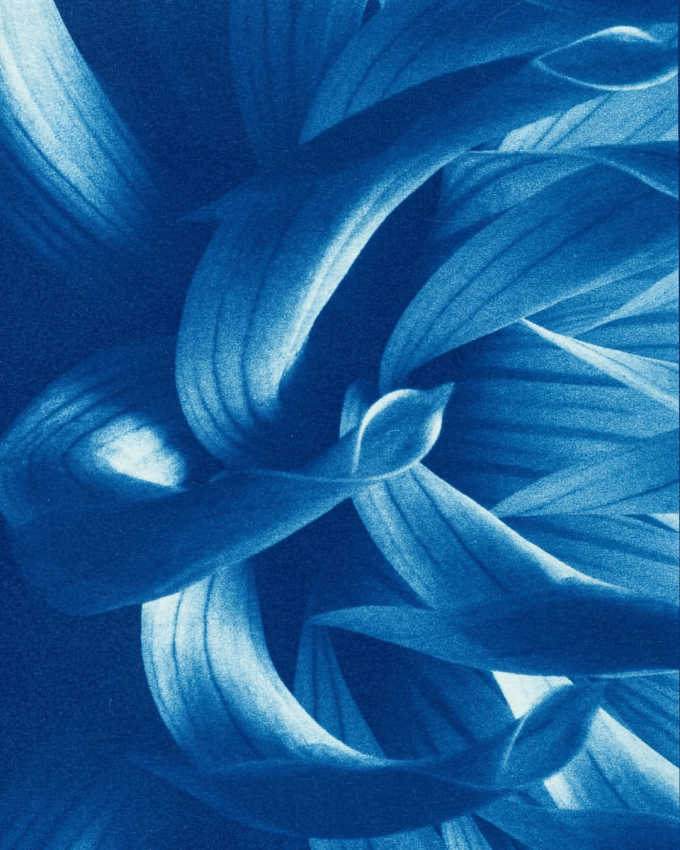

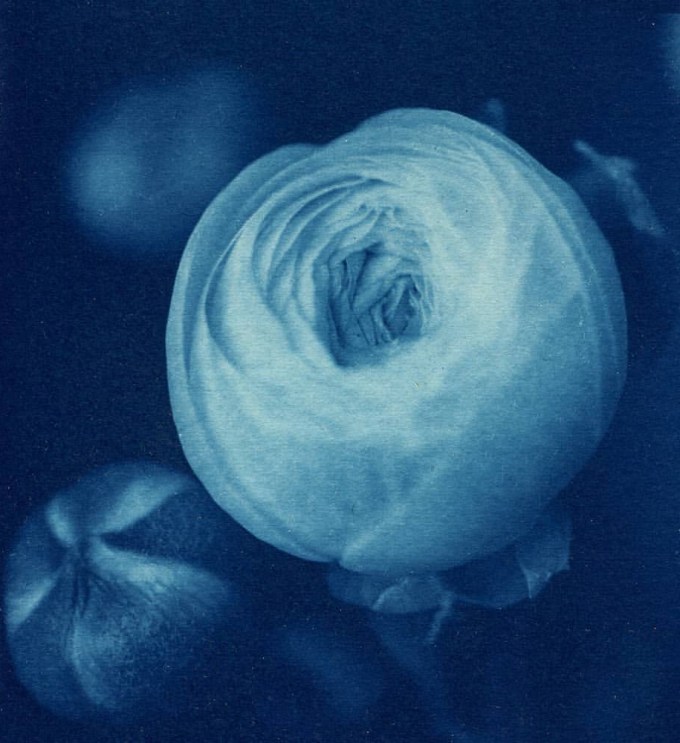

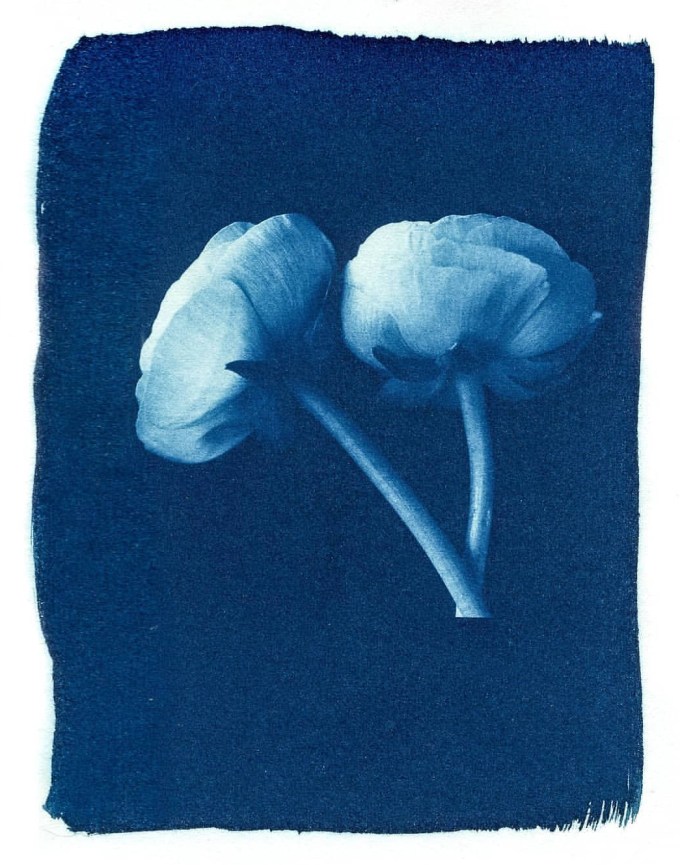

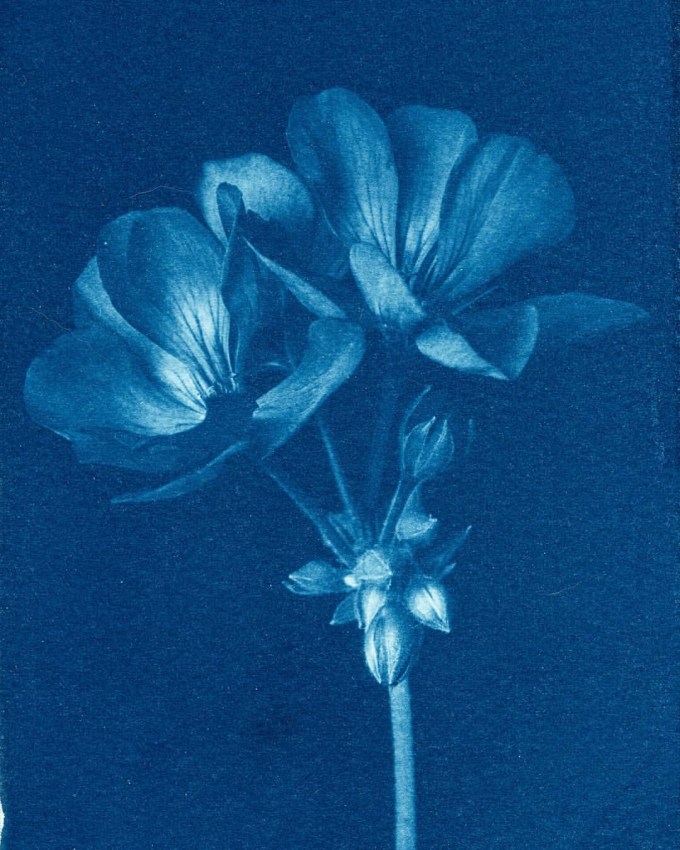

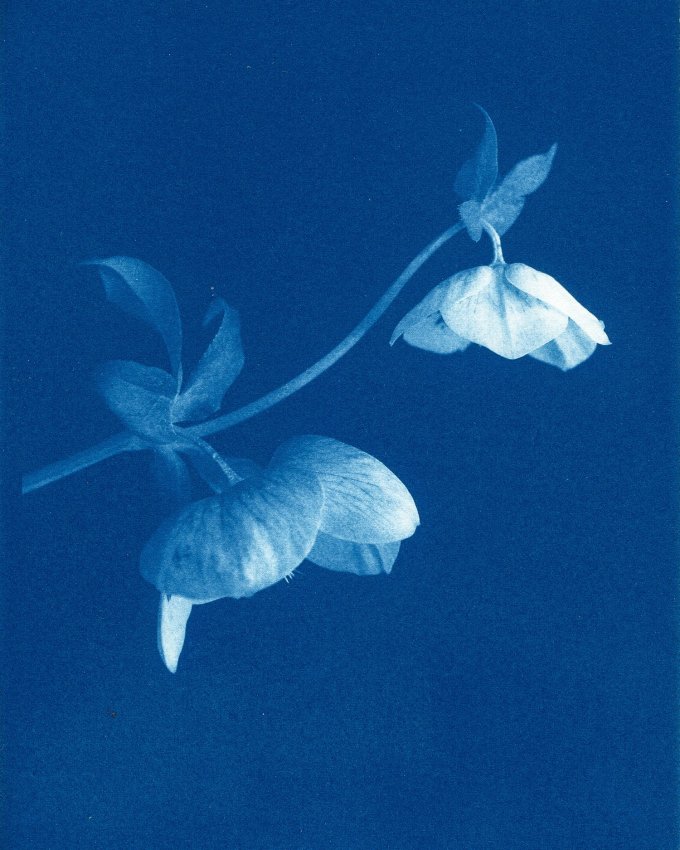

When Florence Nightingale championed the healing power of beauty a century and a half before modern medicine attested to it, she held up two prime forms of it: art and flowers. Hobley’s tender, haunting cyanotypes unite the two in a single rapture of beauty that feels nothing less than medicinal. I live with two of her dahlias and regularly look up at them from my writing stand for a vivifying infusion of delight.

It is owing to these causes that I am unable to present the results at which I have arrived, in any sort of regular or systematic connection; nor should I have ventured to present them at all to the Royal Society, but in the hope that, desultory as they are, there may yet be found in them matter of sufficient interest to render their longer suppression unadvisable, and to induce others more favourably situated as to climate, to prosecute the subject.

Finally, in 1842, he arrived at an economical printing process to capture the light of the world, the light that gives form and substance to everything we see, in otherworldly blueprints — a slow-reacting solution of equal parts potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate, sensitive to the blue portion of the spectrum spilling into ultraviolet, developed and fixed by only water and sunlight.

Two centuries hence, London-based artist Rosalind Hobley unites our twin responsibilities to nature and human nature, to beauty and wonder, in her cyanotype portraits of flowers, immortalized with ravishing fidelity to a long-ago printing process developed in the golden age of chemistry and wonder, in a world far less impatient than ours and far more reverent of the artist’s work, which is the work of noticing and reverencing.

When Dickinson was a teenager, across the Atlantic, the self-taught botanist Anna Atkins pioneered another art-form for celebrating nature — visual poetry of a kind the world had never before encountered. Her stunning cyanotypes of sea algae engraved her onto our common record as the first person to illustrate a book with photographs and the first woman known to take a photograph at all.

Hobley builds on a long lineage of wonder at the boundary of art and science. In 1839, the polymathic astronomer John Herschel coined the word “photography” to name the process his friend Henry Fox Talbot had developed, not yet knowing he was naming a revolution in our way of seeing and our way of being. Herschel sensed that something vast and beautiful lay hidden beyond this new horizon of photochemical reactions — something that would reveal to the human eye forms of light to which we are born blind, those wondrous unseen extremes bookending the visible spectrum: the luxurious wavelengths of infrared light, which his own father — William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus and brother to the world’s first professional female astronomer — had detected when John was eight, and the petite band of ultraviolet light, which the German chemist Johann Ritter had discovered a year later.

If you too would like to live with these time-traveling beauties cross-pollinating the ephemeral and the eternal, many of Hobley’s flowers are available as prints. Complement them with Lia Halloran’s cyanotype celebration of trailblazing women in astronomy, then revisit the stunning botanical art of Herschel’s contemporary Clarissa Munger Badger, who inspired Emily Dickinson, and this epochs-wide meditation on flowers and the meaning of life.

So began Herschel’s devotion to our species’ consciousness-defining history of pondering the nature of light. For three years, he toiled to understand how different elements react to sunlight. His experiments were constantly derailed by bad English weather, beginning with an uncommon spell of “extreme deficiency of sunshine during the summer and autumn of the year 1839” and nearly ending with an “almost unprecedented continuance of bad weather during the whole of the [1841] summer and autumn.”

“To be a flower,” Emily Dickinson wrote in one of her finest poems, “is profound responsibility.”