But rather than offended, Emerson must have been pleased with Whitman’s decision to stay his course — for Whitman was in many ways the embodiment of the spirit Emerson so fiercely celebrated against the tide of his time: a spirit animated by the central doctrine “trust thyself,” anchored in resolute resistance to the tyranny of opinion, and rooted in the belief that had gotten Emerson banned from Harvard’s campus for thirty years when he was Whitman’s age — the belief that divinity is to be found not in some outside deity, but in the human soul itself, in its fidelity to itself as a fractal of nature, a particle of the perfect totality of the universe, which Margaret Fuller — Emerson’s greatest influence — called “the All.”

A century and a half before Wendell Berry observed that “true solitude is found in the wild places, where… one’s inner voices become audible,” Emerson writes:

“I felt down in my soul the clear and unmistakable conviction to disobey all, and pursue my own way,” the young Whitman wrote of his momentous critique-walk with his greatest literary hero, Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803–April 27, 1882) — the walk from which the young poet wrested his wisdom on how to keep criticism from sinking your soul, for Emerson, who had inspired Leaves of Grass, had just lashed upon one of its primary poem sequences “argumentstatement, reconnoitring, review, attack, and pressing home, (like an army corps in order, artillery, cavalry, infantry,) of all that could be said against [it].”

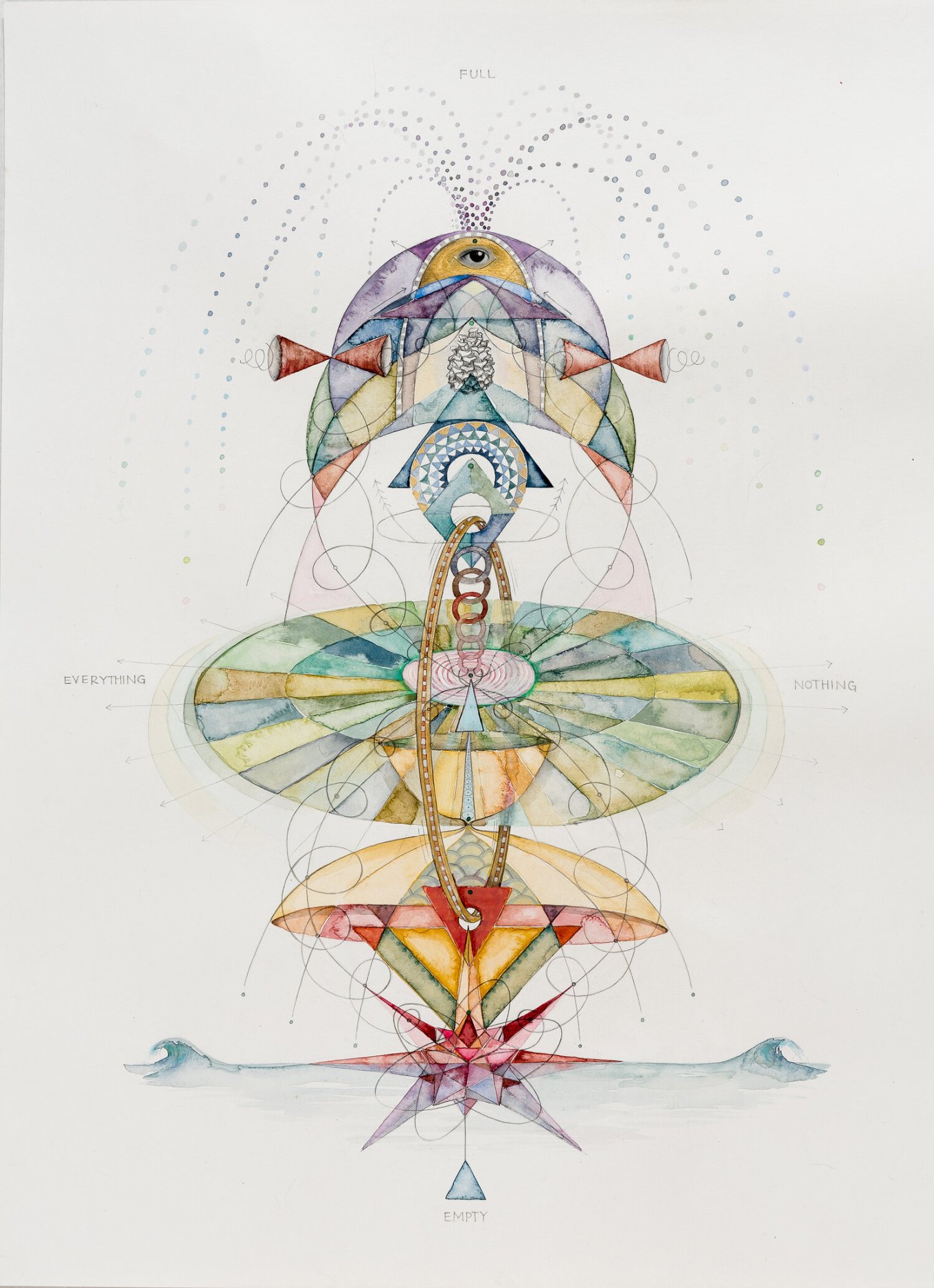

In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

Complement with Emerson’s young protégé Thoreau on solitude and the salve for melancholy, artist Rockwell Kent on wilderness, solitude, and creativity, and Kahlil Gibran on silence, solitude, and the courage to know yourself, then revisit Hermann Hesse on the wisdom of the inner voice and Octavia Butler on the meaning of “God.”

What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think. This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness. It is the harder because you will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man* is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

In “Nature” — perhaps his finest essay, for being the most all-encompassing and spiritually lucid — he considers what solitude actually means, refuting the common conception of it as a kind of self-isolation from other selves behind the walls of seclusion, for even the thinking mind, the writing mind, the creating mind is a symposium of outside voices when trapped within itself.

[…]

Throughout Emerson’s immense body of work, no question vibrates more resonantly than that of how to trust yourself. He takes it up in his essay “Character,” found in his indispensable Essays and Lectures (public library | free ebook):

To go into solitude, a man* needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society. I am not solitary whilst I read and write, though nobody is with me. But if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars.