The study of Shells, or testaceous animals, is a branch of natural history which, although not greatly useful to the mechanical arts, or the human economy, is, nevertheless, by the beauty of the subjects it comprises, most admirably adapted to recreate the senses, to improve the taste or invention of the Artist, and, finally and insensibly, to lead to the contemplation of the great excellence and wisdom of the Divinity in their formation.

Perry notes how deeply and widely shells have permeated the human cultural experience over the ages — from the drinking cups used in ancient religious rituals to the purple dye extracted from a delicate Mediterranean shell of the genus Polyplex, with which the early poets produced the oldest surviving writings, to the volutes gracing the iconic capital columns of Grecian architecture, which borrow their shape from the geometry of the ram’s horn squid, the only surviving member of the genus Spirula.

In an era when the chief purpose of science was seen as a confirmation of the perfection of a Creator-god, half a century before Darwin began shattering the brittle creationist mythology of unreason with the anvil of his elegantly reasoned evolutionary revelation, Perry opens the book with a poetic sentiment reverencing the aesthetic and spiritual rewards of shells beyond their science:

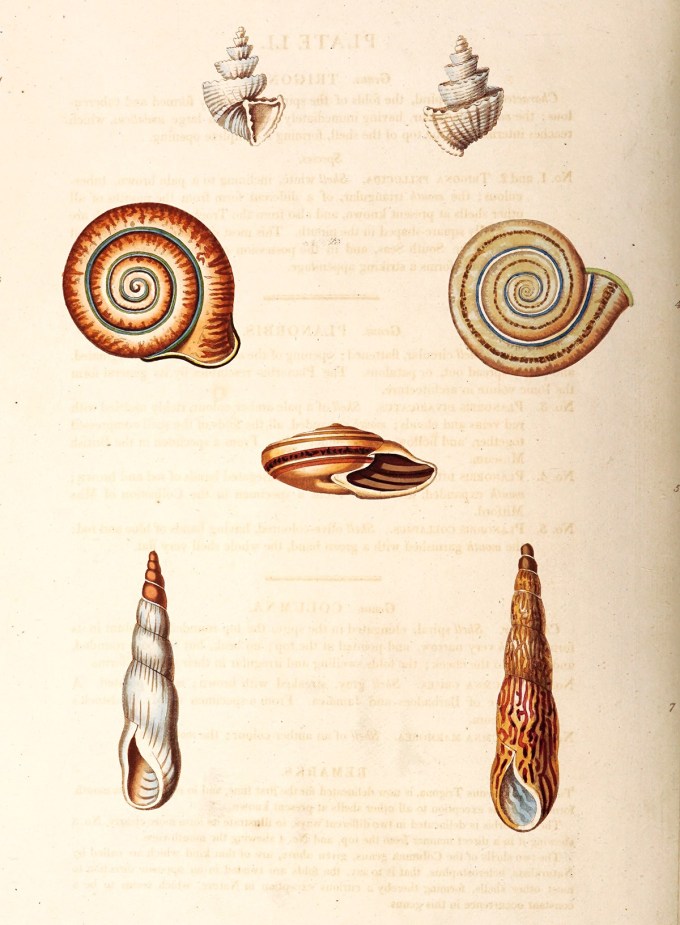

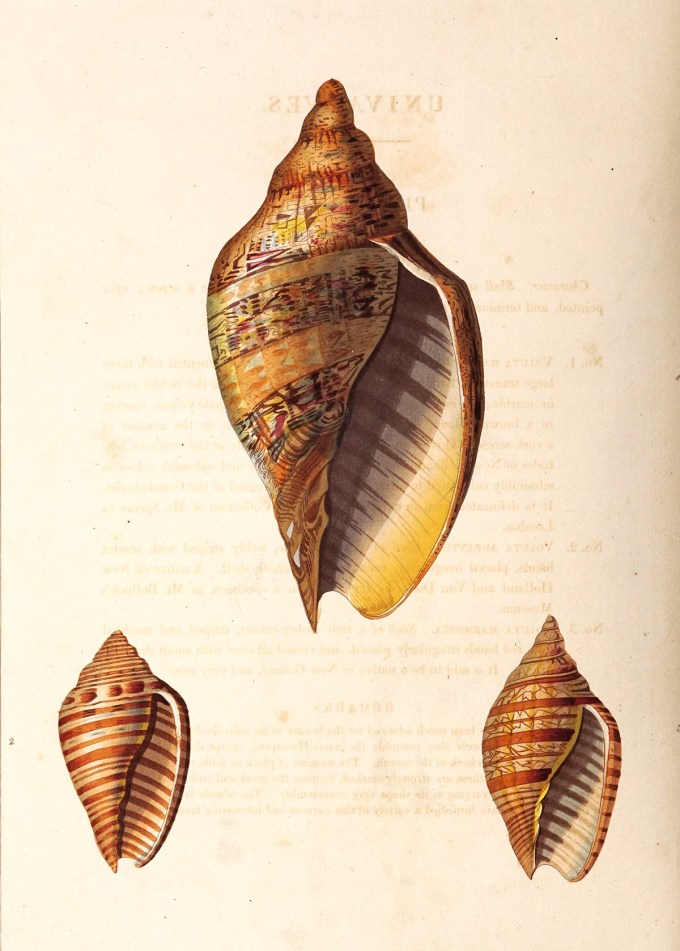

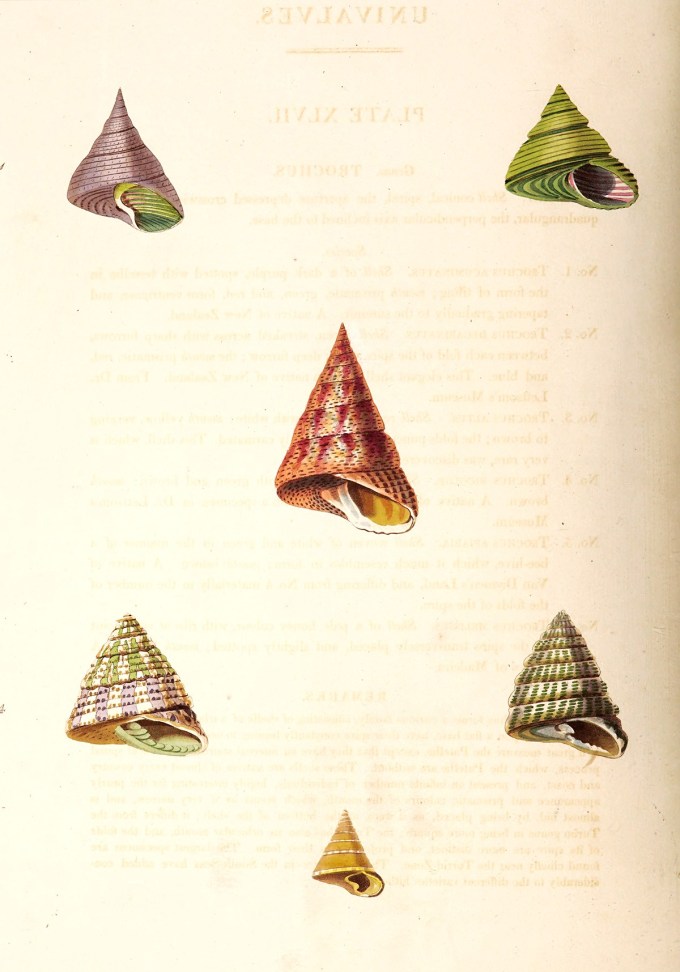

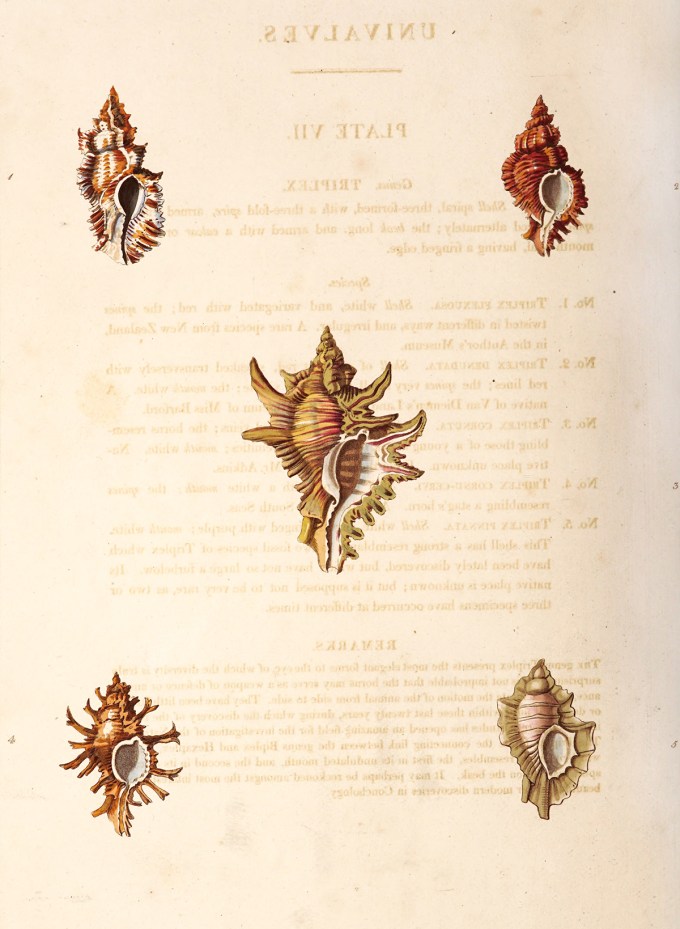

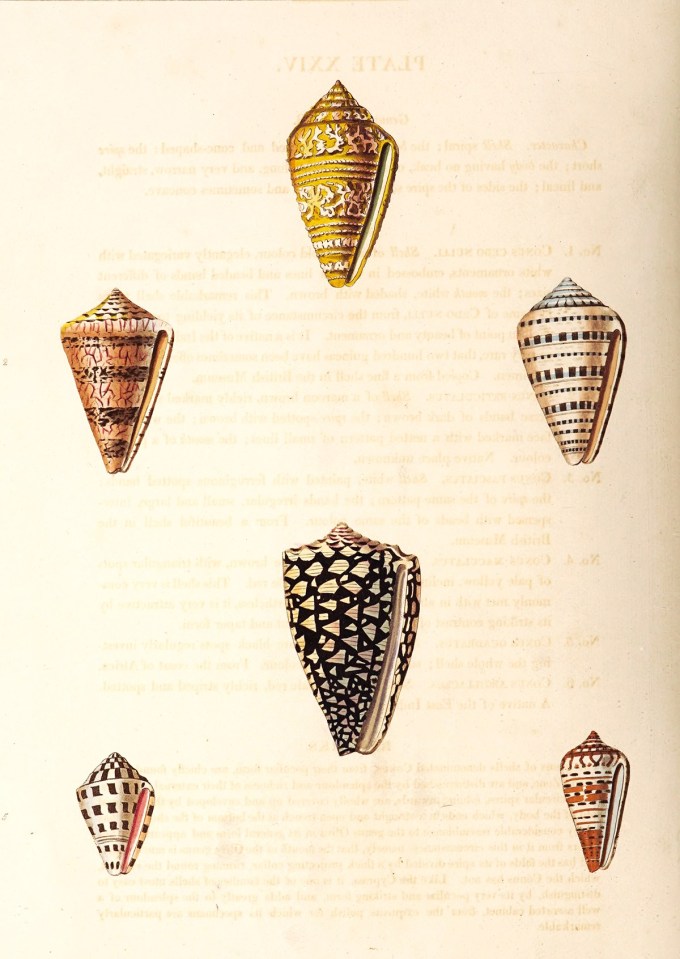

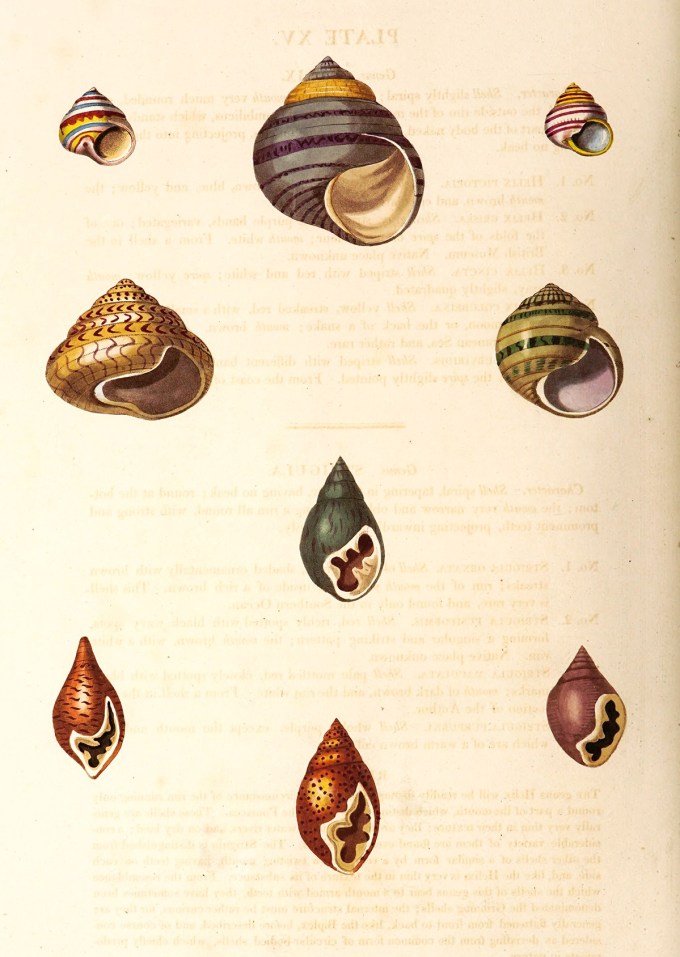

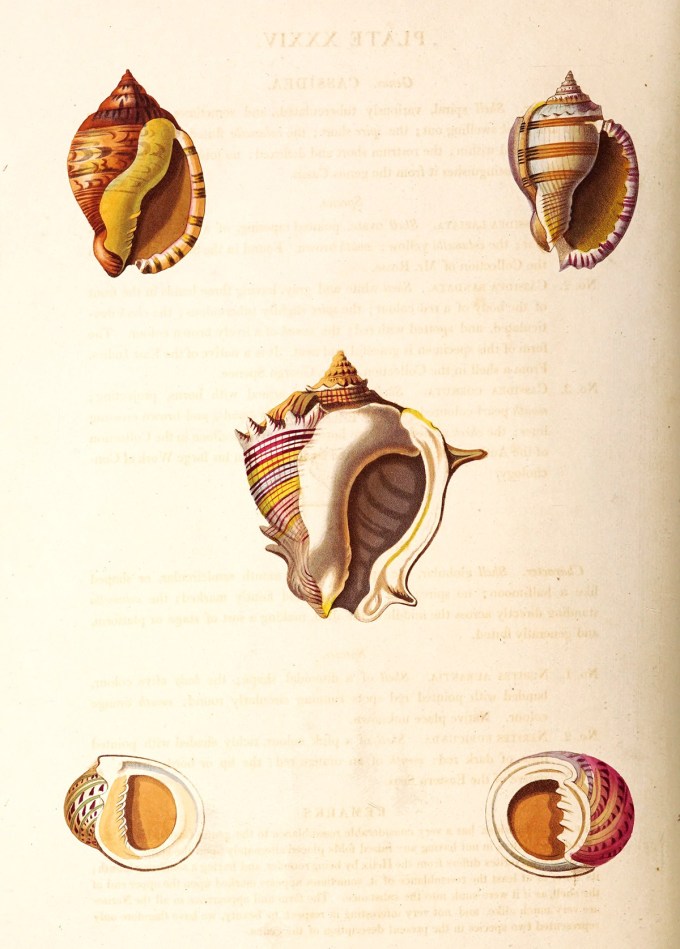

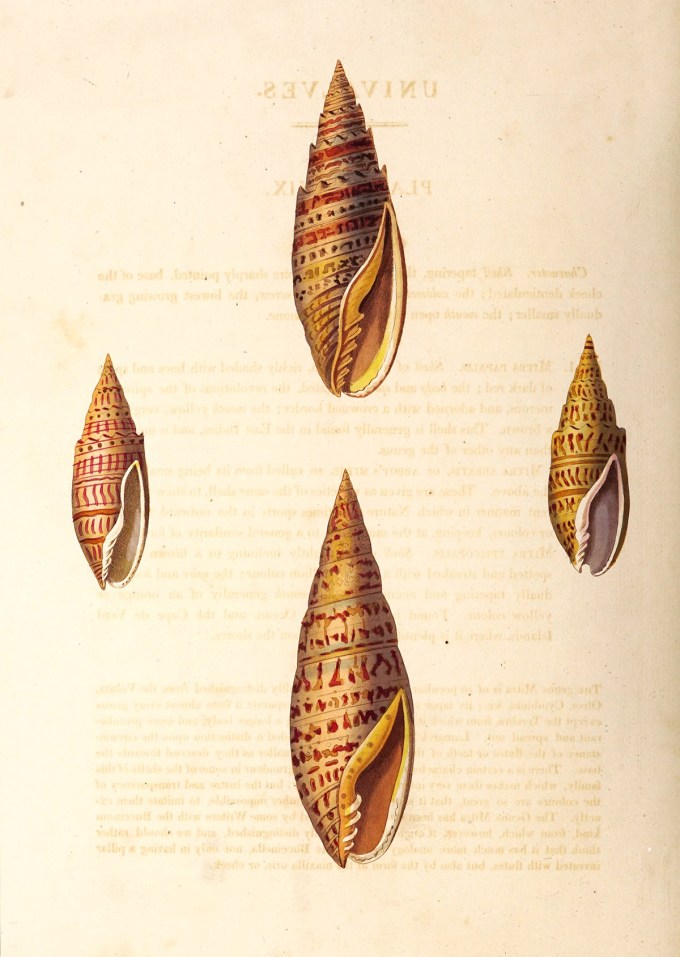

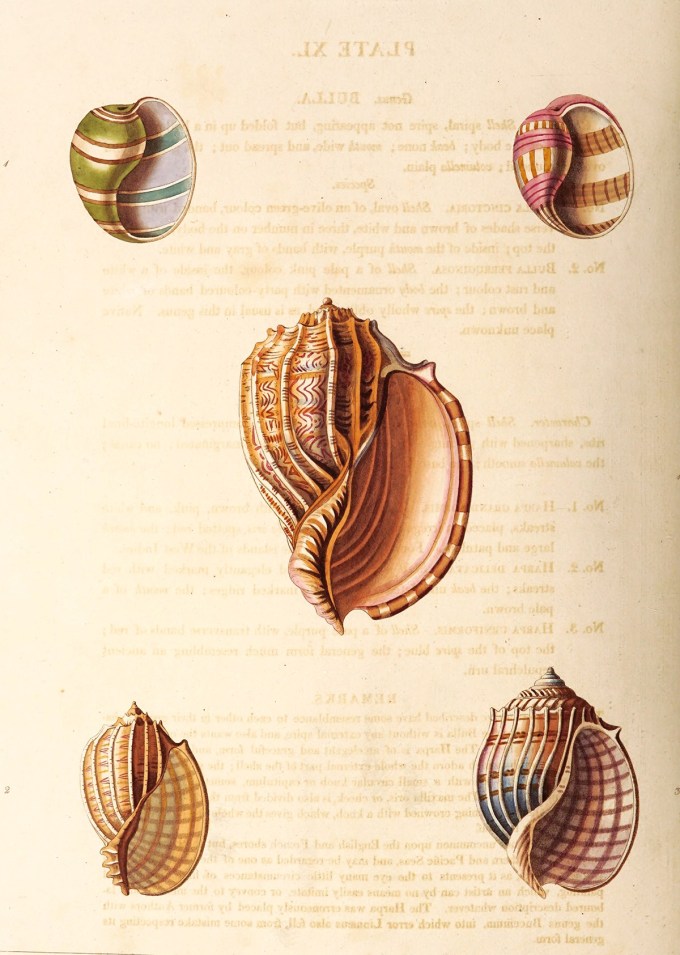

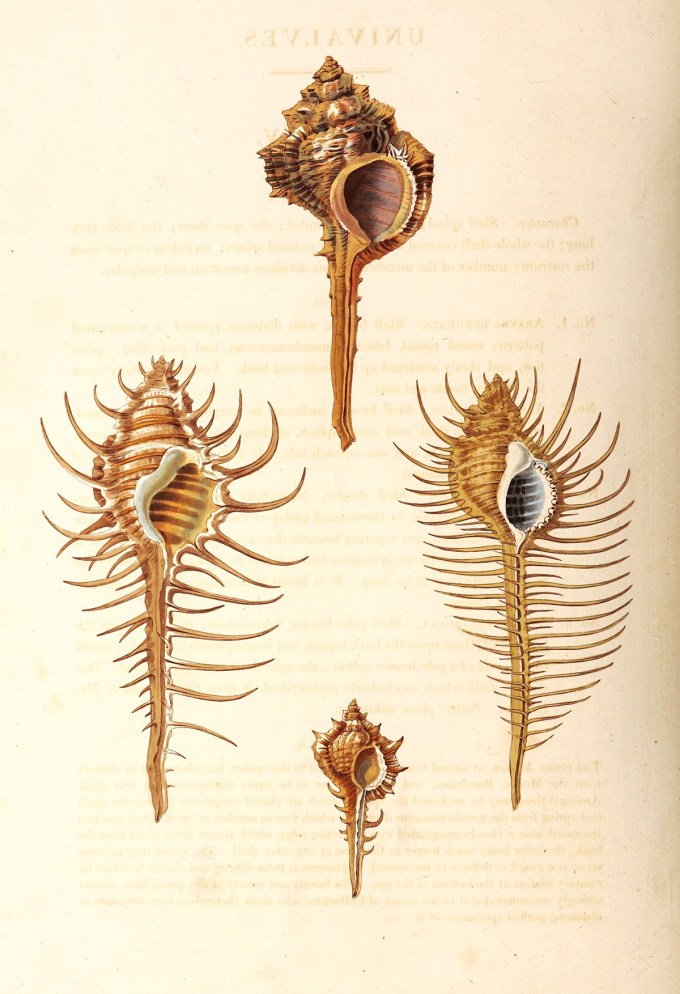

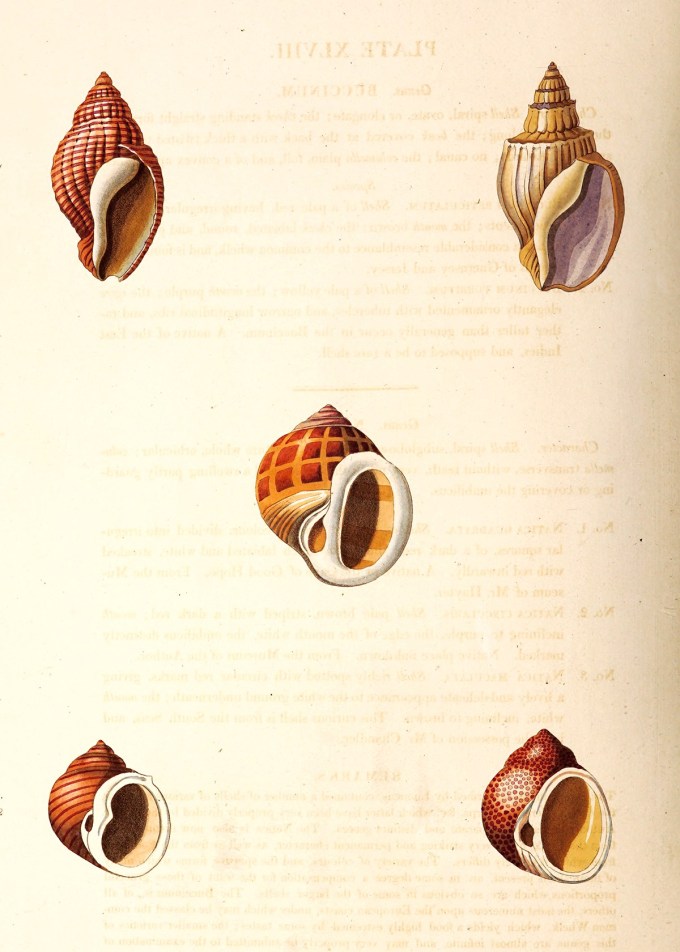

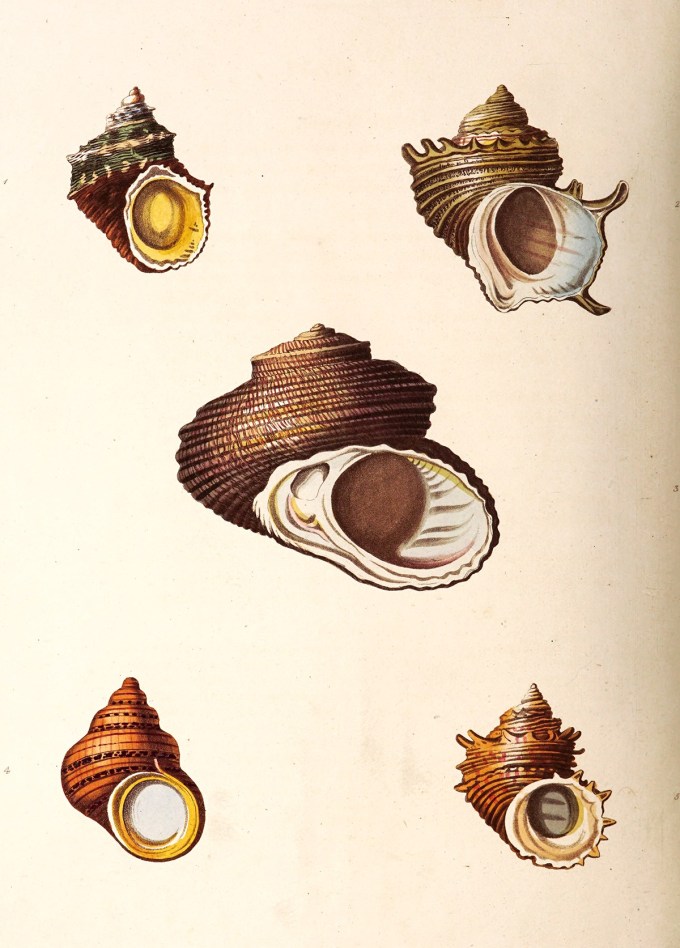

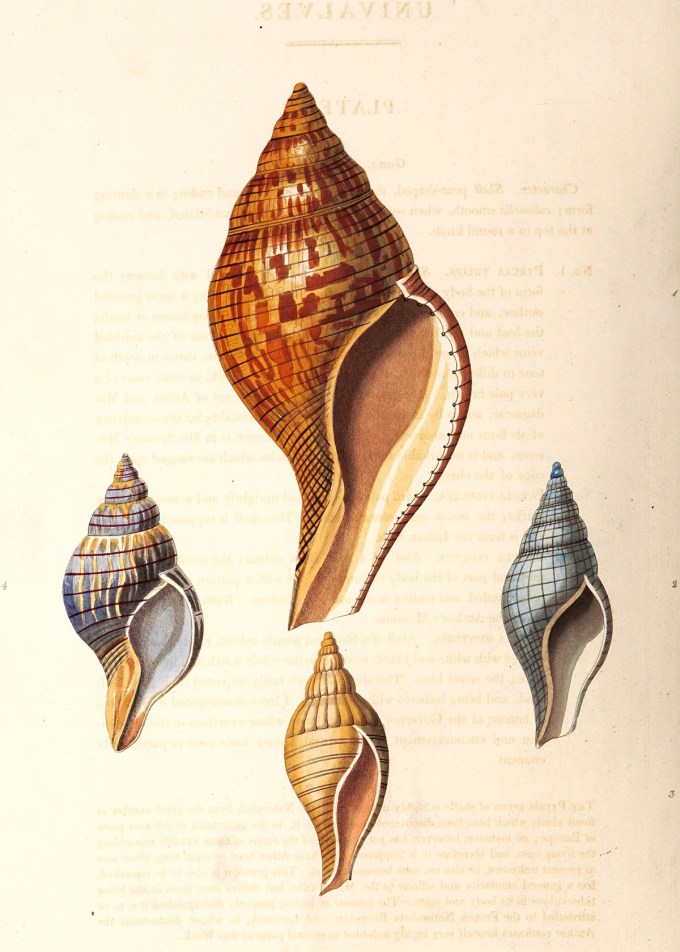

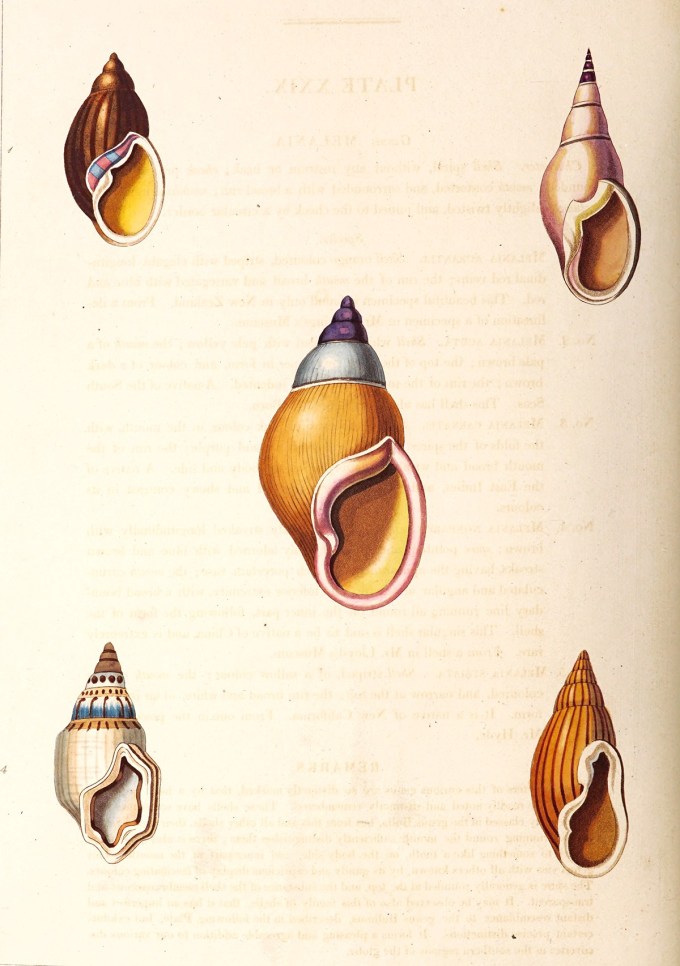

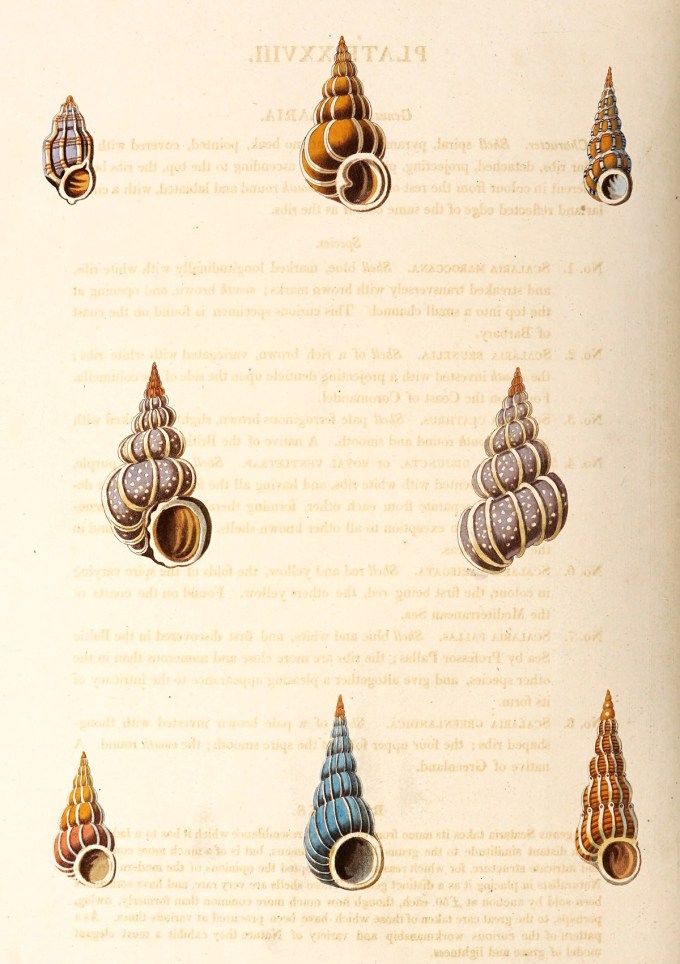

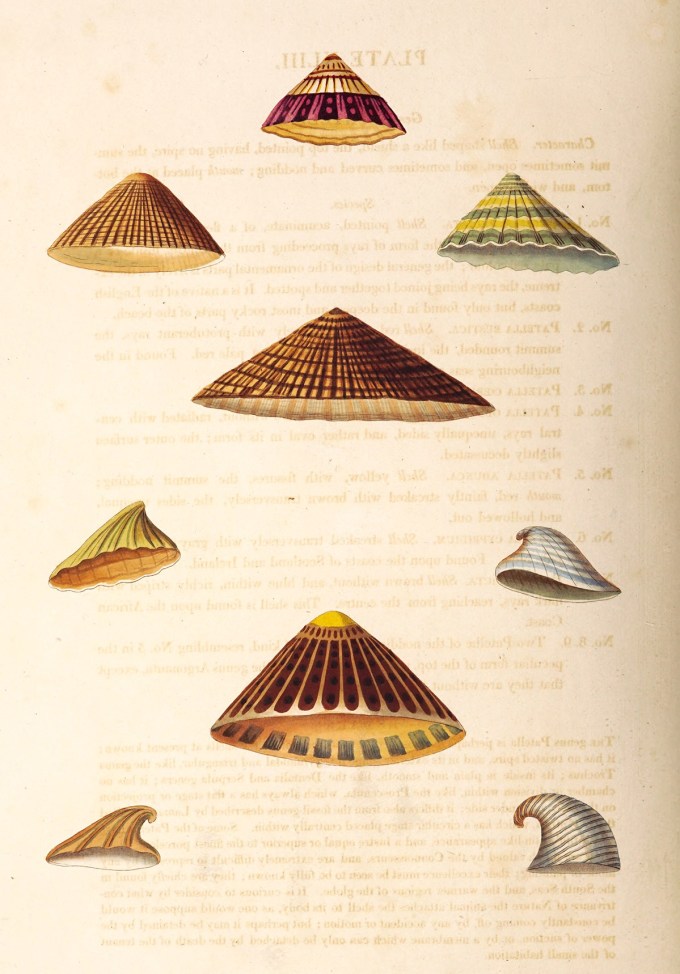

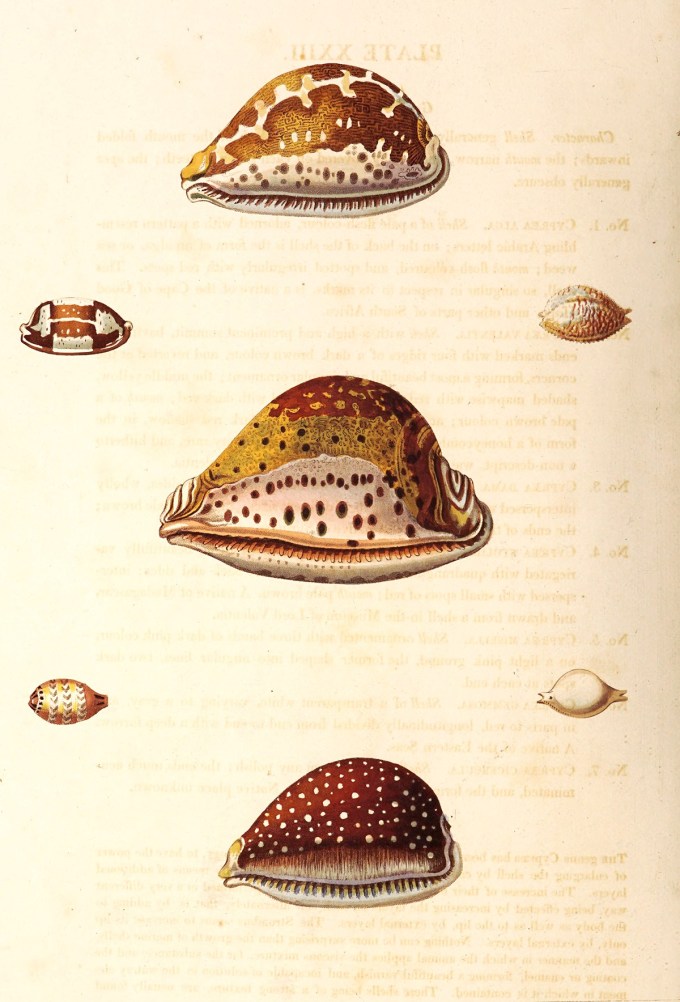

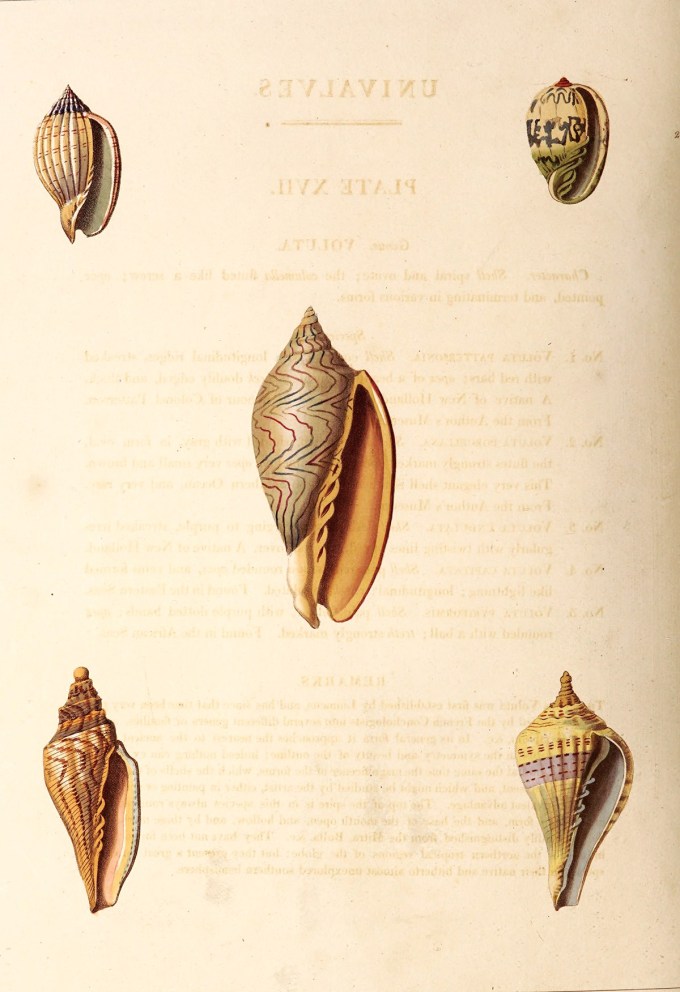

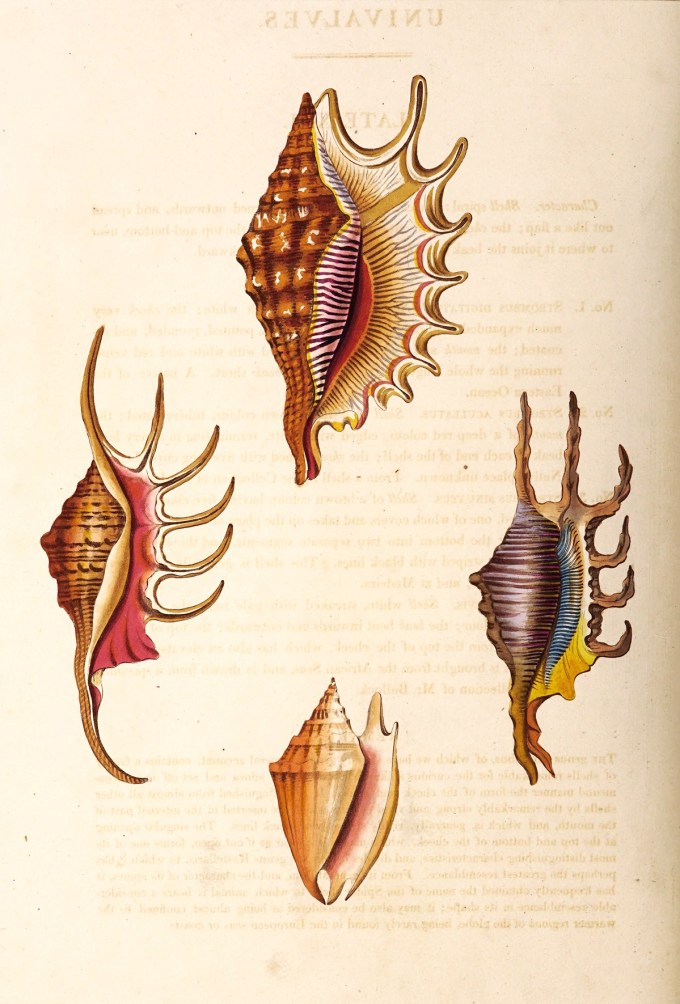

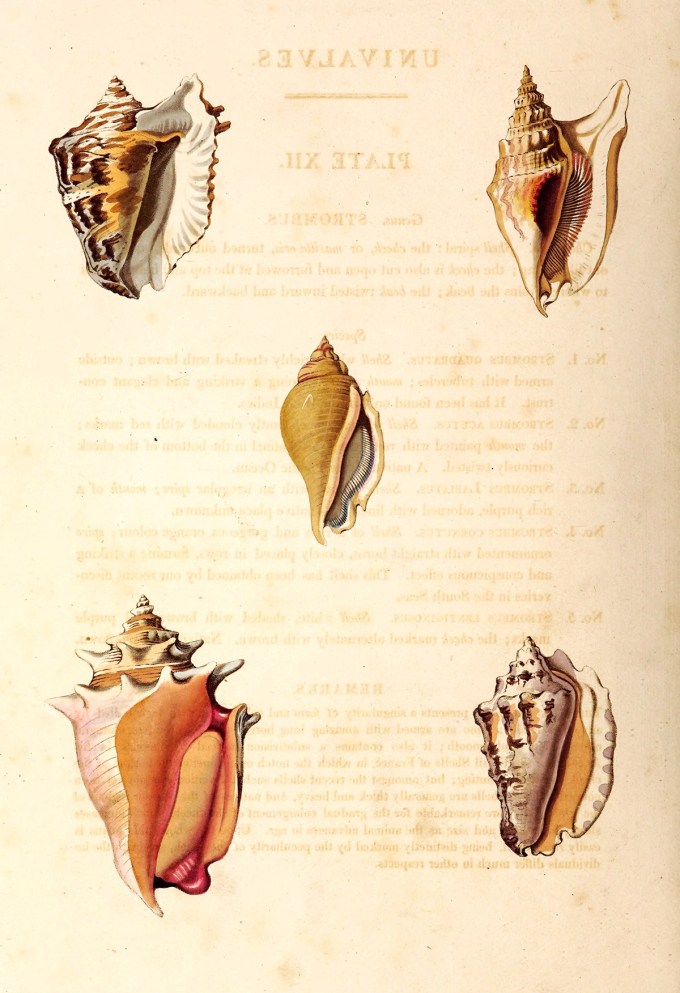

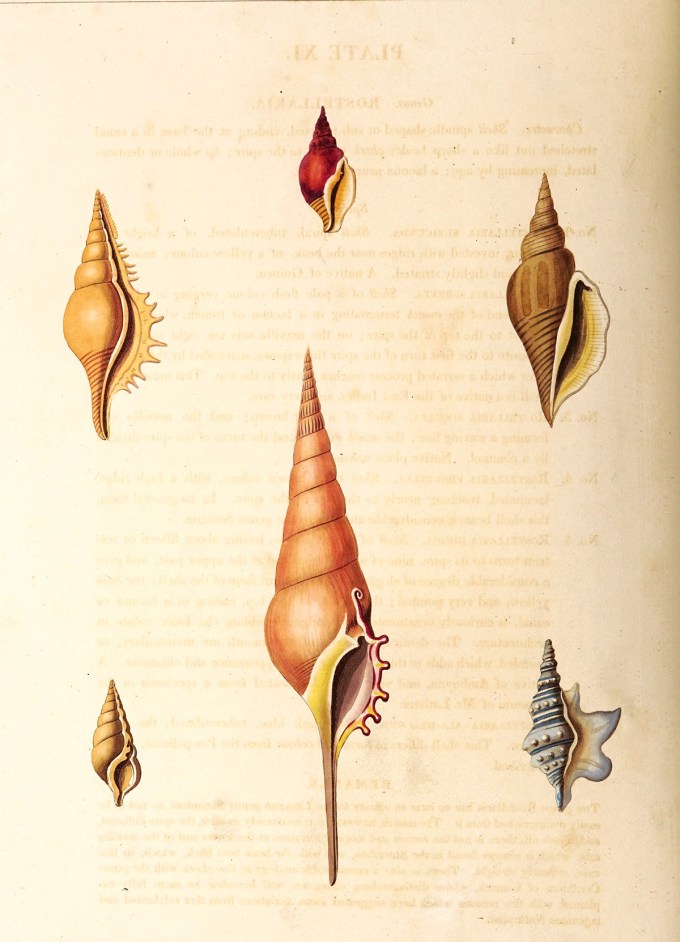

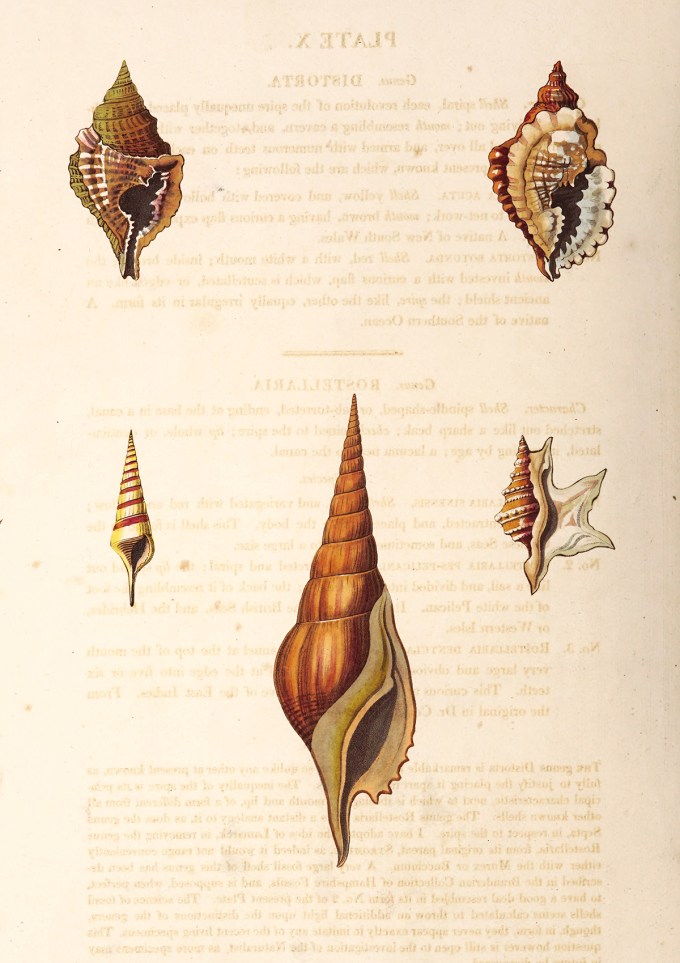

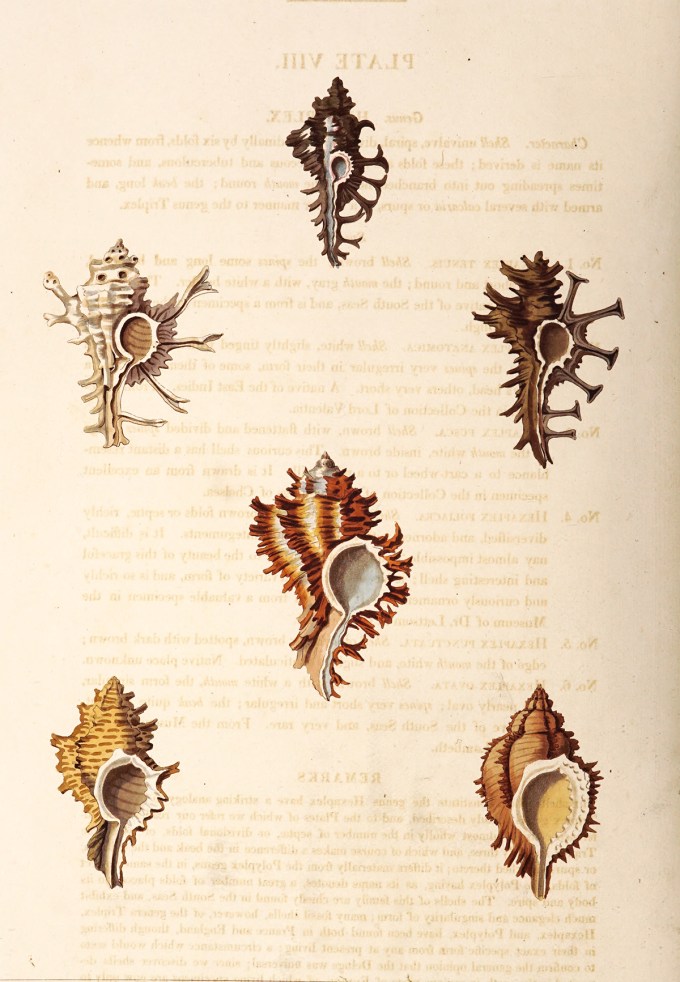

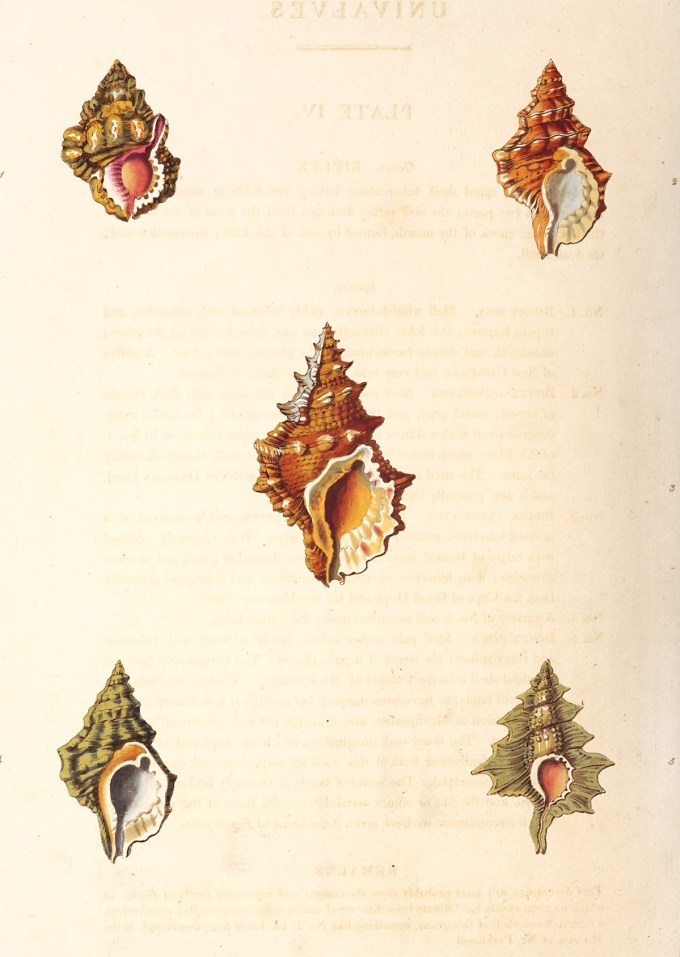

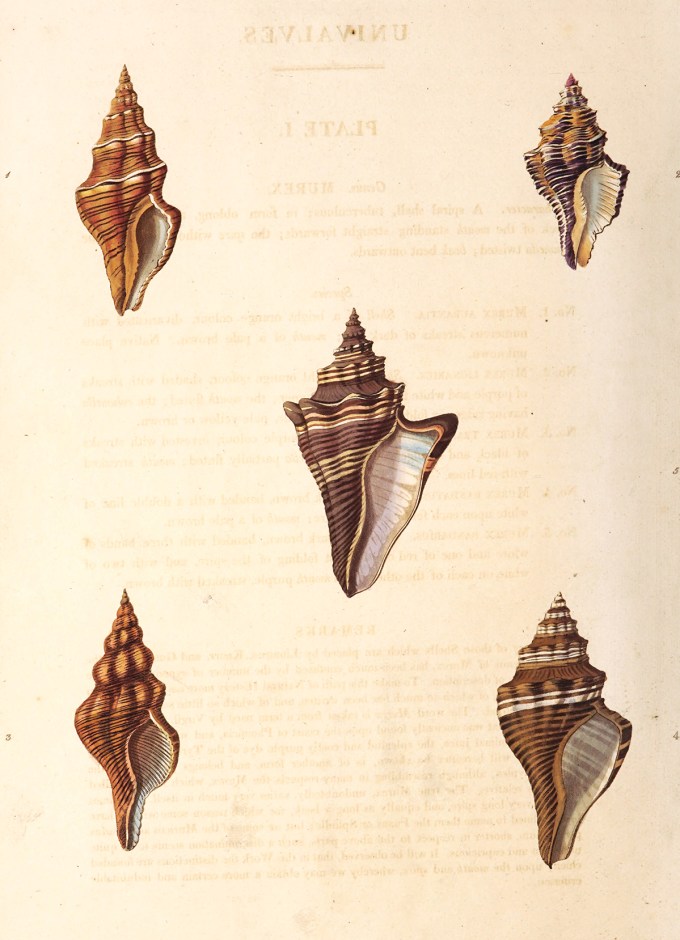

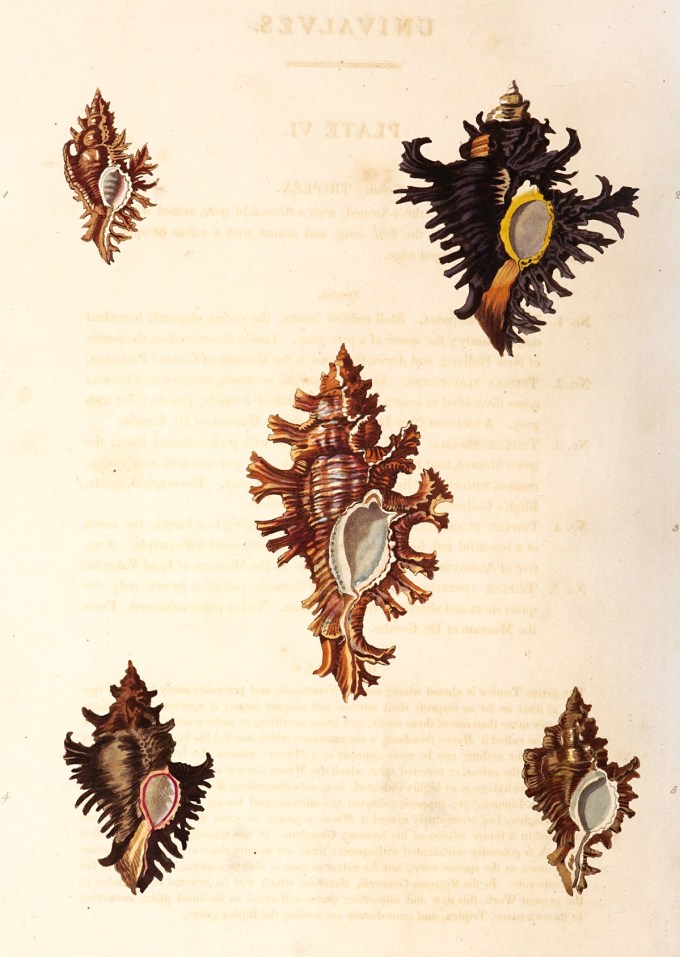

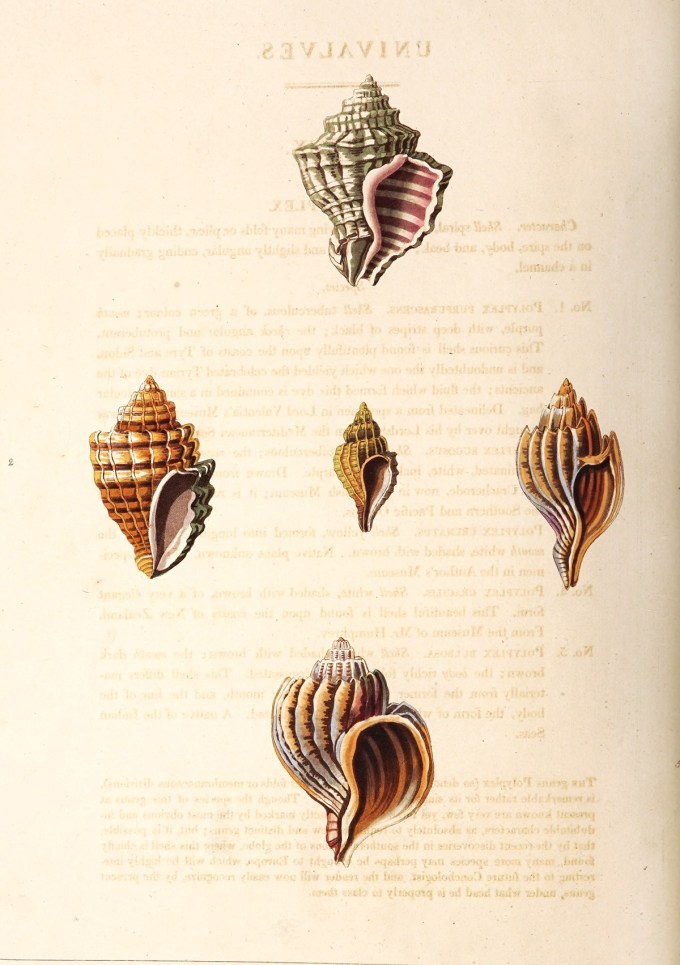

Born in 1771, the English naturalist and malacologist George Perry became the era’s preeminent scholar of shell-bearing mollusks. In 1811, he published his research in this exquisite 266-page treasure, featuring sixty-two color plates of strange and wondrous creatures, illustrated by the English artist and engraver John Clarke, “executed from the natural specimens and including the latest discoveries” — the mobile homes of marine creatures turned voluptuaries of geometry and color, elaborate living urns, lavish lampshades for the palace of some sea god, miniature Hindu temples, gorgeous drag queens of the deep, otherworldly amphoras from the bottom of this spectacular world.

For over half a century the Cooper Union has given, in order to advance Science and Art, education to over 180,000 men and women, regardless of race or creed, without money and without price.

Working with the copy digitized by the wonderful Biodiversity Heritage Library, I have restored and color-corrected the finest, most beautiful, most otherworldly of these visual serenades to the diverse splendor of our irreplaceable world to make them available as prints and face masks — part of the growing collection of vintage science face masks, benefiting The Nature Conservancy.

Complement with some psychedelic fishes from the world’s first encyclopedia of marine life in color, some candy-colored corals from the world’s first encyclopedia of the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem, and the astonishing butterfly drawings of two nineteenth-century Australian teenage sisters who fomented one of the greatest conservation triumphs of the twenty-first century.

In 1893, moved to aid this ennobling endeavor, the wealthy widow Mary Stuart established a ,000 annual fund — close to 0,000 today — devoted to acquiring important, scrumptiously illustrated rare books for the Cooper Union library. Among them is the world’s first comprehensive illustrated encyclopedia of shell-dwelling animals: Conchology, or, The Natural History of Shells — a work I discovered by a sidewise research trail during my tender adventures in snailhood.

A century-old annual report by one of the greatest public-good institutions our civilization has produced — New York’s Cooper Union, site of the speech that bewinged Lincoln’s ascent to the presidency, alma mater to some of the most visionary artists and thinkers of the past century and a half, founded by the inspired mechanic Peter Cooper the year Darwin published On the Origin of Species — begins with this plainspoken benediction of a mission statement: