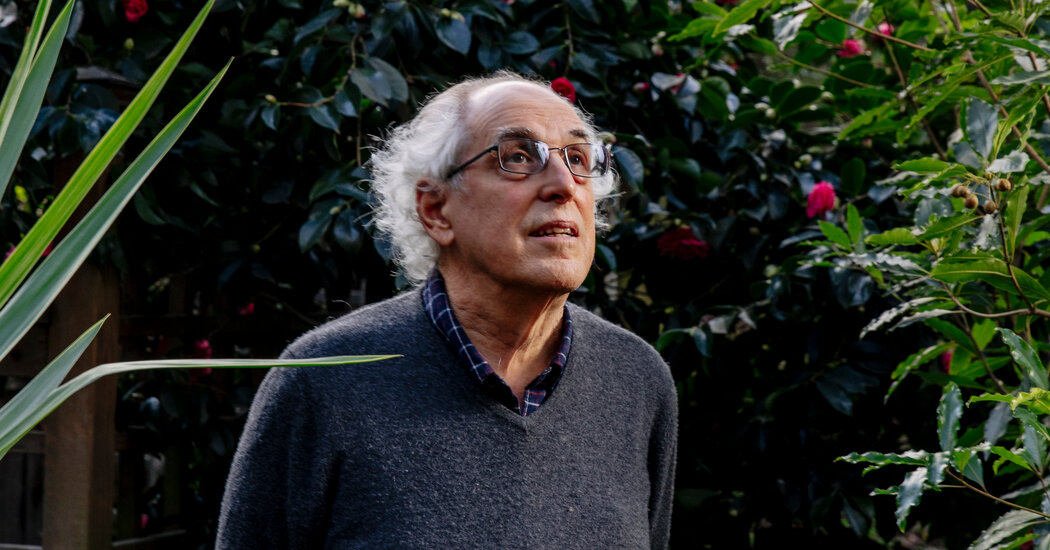

His biggest worry, though, is that we still mostly fail to acknowledge that we live in a roaring attention economy. In other words, we tend to ignore his favorite maxim, from the writer Howard Rheingold: “Attention is a limited resource, so pay attention to where you pay attention.”

“You could just see how there were so many disparate factions of believers there,” he said, remarking on the glut of selfies and videos from QAnon supporters, militia members, Covid-19 deniers and others. “It felt like an expression of a world in which everyone is desperately seeking their own audience and fracturing reality in the process. I only see that accelerating.”

Mr. Goldhaber said that looking at Mr. Trump through the lens of attention gives a deeper understanding of his appeal to supporters and, potentially, how to combat his style of politics. He said that many of the polarizing factors in the country are, in essence, attentional. Not having a college degree, he argued, means less attention from corporations or the economy at large. Living in a rural area, he suggested, means being farther from cultural centers and may result in feeling alienated by the attention that cities generate in the news and in pop culture. He said that almost by accident, Mr. Trump tapped into this frustration by at least pretending to pay attention to them. “His blatant racism and misogyny was an acknowledgment to his supporters who feel they deserve the attention and aren’t getting it because it is going to others,” he said.

While Mr. Goldhaber said he wanted to remain hopeful, he was deeply concerned about whether the attention economy and a healthy democracy can coexist. Nuanced policy discussions, he said, will almost certainly get simplified into “meaningless slogans” in order to travel farther online, and politicians will continue to stake out more extreme positions and commandeer news cycles. He said he worried that, as with Brexit, “Rational discussion of what people stand to gain or lose from policies will be drowned out by the loudest and most ridiculous.”

Mr. Goldhaber was conflicted about all of this. “It’s amazing and disturbing to see this develop to the extent it has,” he said when I asked him if he felt like a Cassandra of the internet age. Most obviously, he saw Mr. Trump — and the tweets, rallies and cable news dominance that defined his presidency — as a near-perfect product of an attention economy, a truth that disturbed him greatly. Similarly, he said that the attempted Capitol insurrection in January was the result of thousands of influencers and news outlets that, in an attempt to gain fortune and fame and attention, trotted out increasingly dangerous conspiracy theories on platforms optimized to amplify outrage.

The big tech platform debates about online censorship and content moderation? Those are ultimately debates about amplification and attention. Same with the crisis of disinformation. It’s impossible to understand the rise of Donald Trump and the MAGA wing of the far right or, really, modern American politics without understanding attention hijacking and how it is used to wield power. Even the recent GameStop stock rally and the Reddit social media fallout share this theme, illustrating a universal truth about the attention economy: Those who can collectively commandeer enough attention can accumulate a staggering amount of power quickly. And it’s never been easier to do than it is right now.

Where do we start? “It’s not a question of sitting by yourself and doing nothing,” Mr. Goldhaber told me. “But instead asking, ‘How do you allocate the attention you have in more focused, intentional ways?’” Some of that is personal — thinking critically about who we amplify and re-evaluating our habits and hobbies. Another part is to think about attention societally. He argued that pressing problems like income and racial inequality are, in some part, issues of where we direct our attention and resources and what we value.