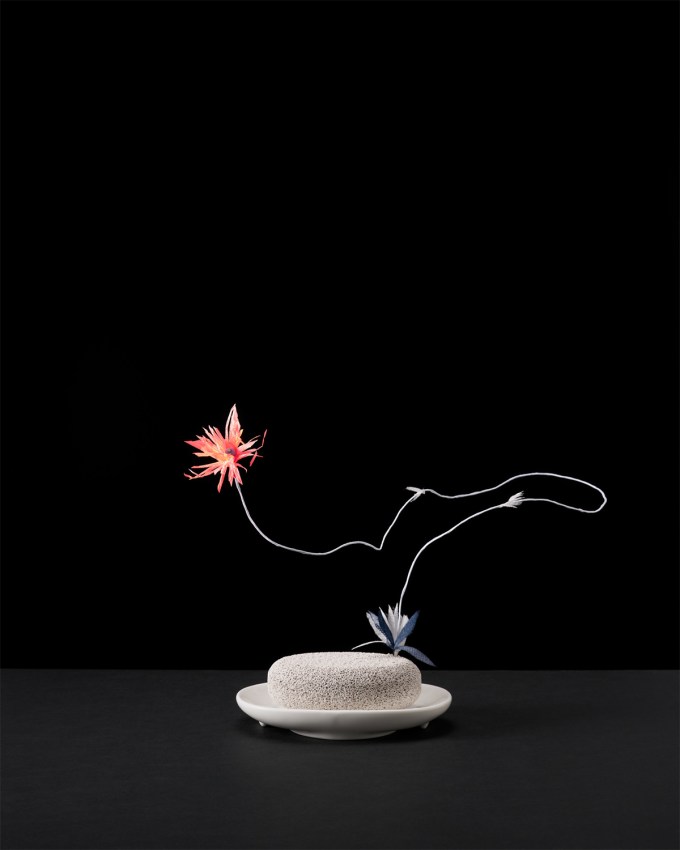

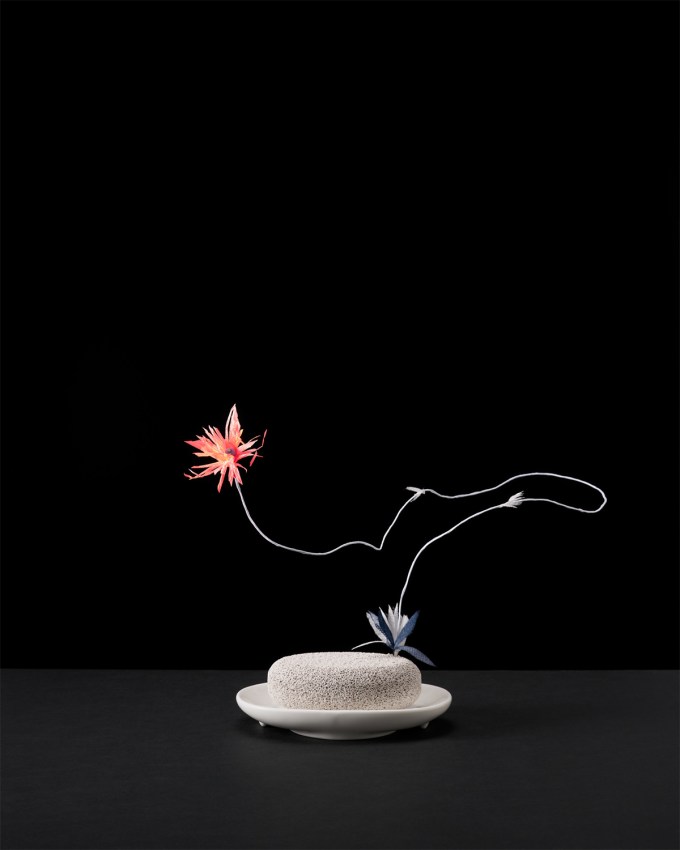

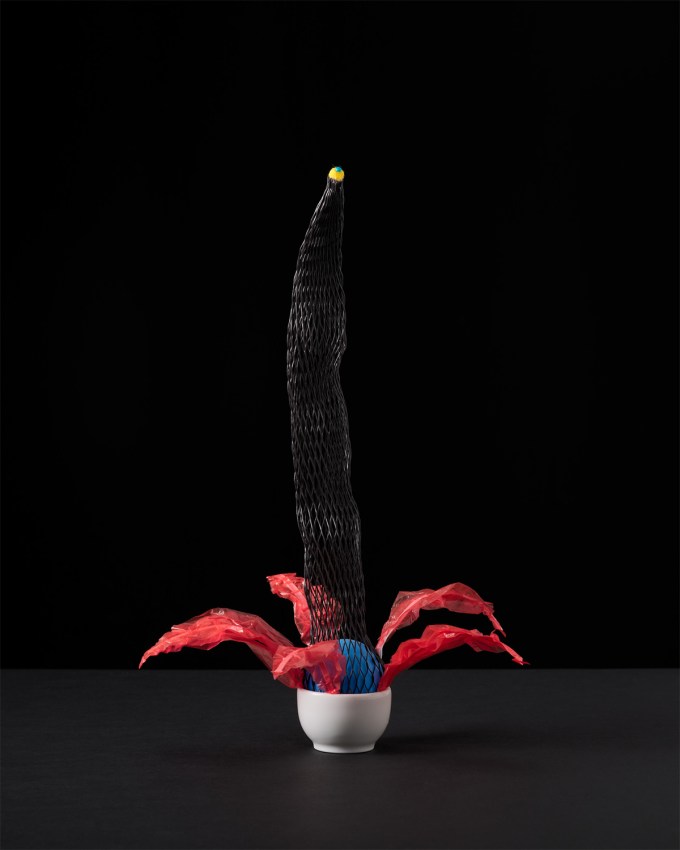

Indeed, radiating from the surreal beauty is a haunting ecological elegy — it is impossible to behold these homages to nature’s creations without the awareness that they are created from the selfsame human materials constellating in colossal gyres to maim entire ecosystems as we go on conveniencing ourselves.

[embedded content]

Complement with some luscious nineteenth-century French botanical illustrations of some of Earth’s strangest and most wondrous actual plants, then revisit Zadie Smith on creativity in the time of COVID.

Life — the measure of our aliveness beyond mere existence — is largely of matter of how much beauty, how much meaning, how much improbable loveliness we can make from the scraps of our losses.

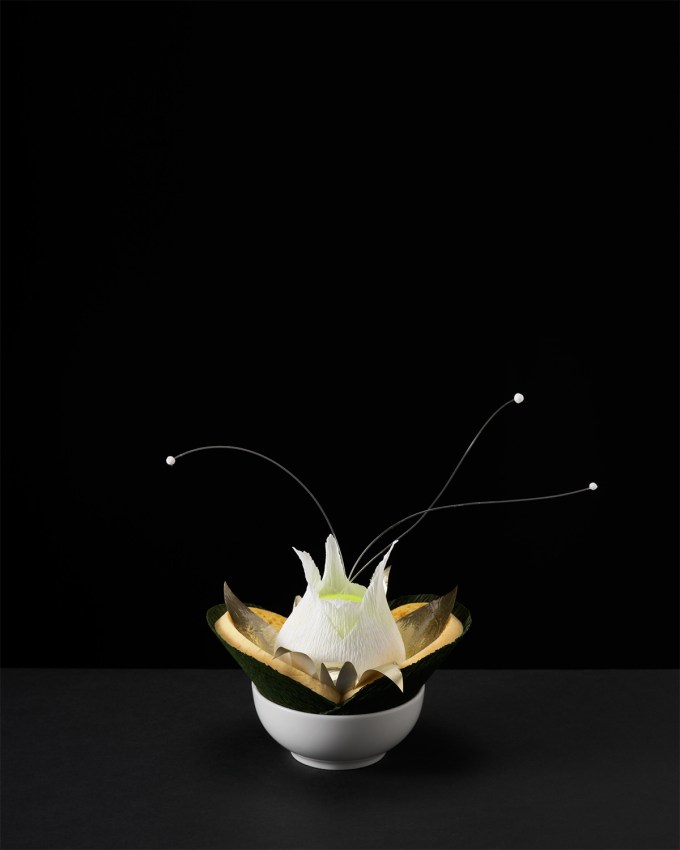

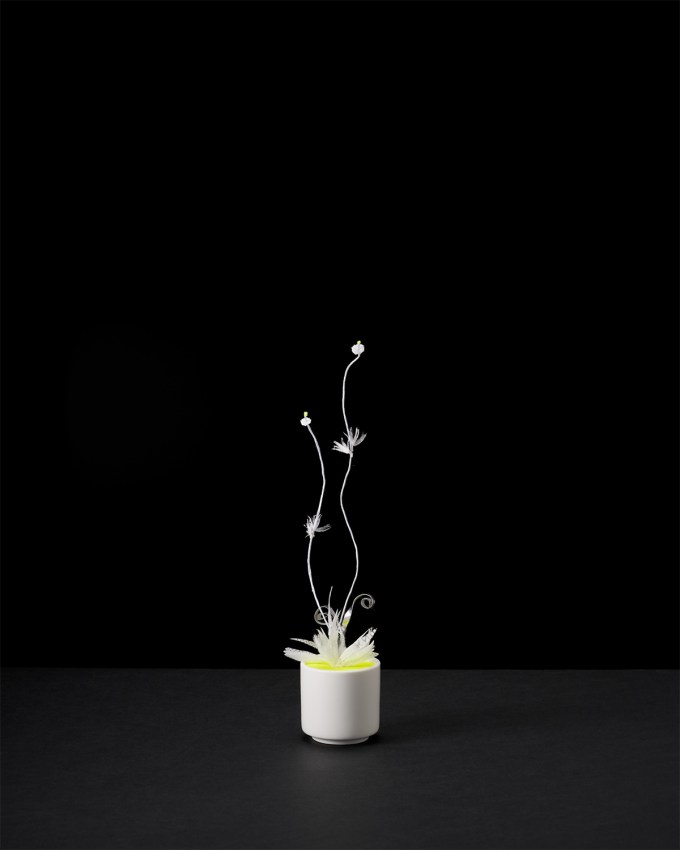

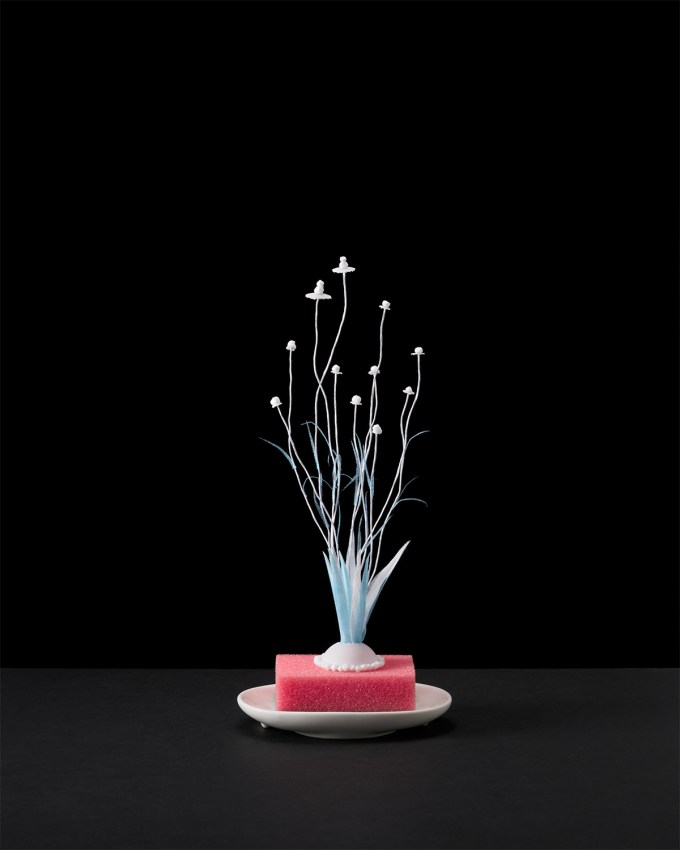

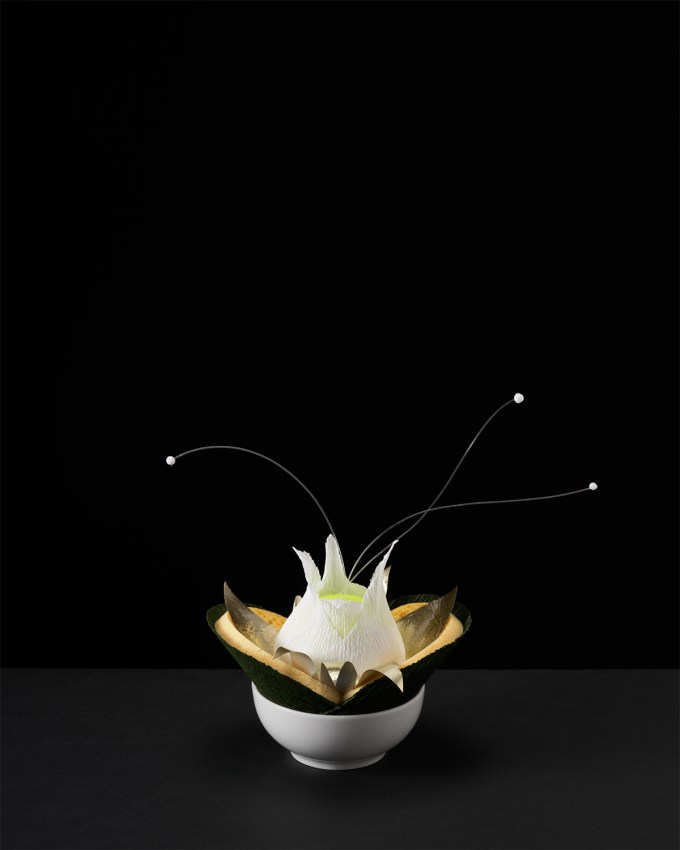

She began making fake plants — delicate and brutal emblems of life made out of the most improbable materials, from tiny tender petals painstakingly cut out of used K-95 face masks to the puffy white flowers found when you break apart styrofoam, one of the most environmentally merciless human-made materials.

And yet something else emerges, too: an improbably lovely reminder that, even at our most artificial, we are not only in constant dialogue with nature but we are nature, calling to mind that lovely Denise Levertov verse from “Sojourns in the Parallel World”:

When artist Nina Katchadourian stared down her trash can in the middle of the lockdown, she was not looking to make art. She was not looking to make meaning. She was looking at a discarded sponge. She was looking to break boredom, to remember the aliveness of life. And suddenly a wilderness of possibility came abloom in her mind.

To Nina’s surprise, working on these fake plants made her intensely more attentive to real plants, even in the most overlooked regions of everyday life — the weeds growing in the cracks of the sidewalk (which are a singular poetic form) became miniature botanical gardens of wonder, evocative of Annie Dillard’s timeless meditation on the miraculous in the mundane.

We call it “Nature”; only reluctantly

admitting ourselves to be “Nature” too.

Rather than replicating existing actual plants, she drew on the greenhouse of the mind to create strange and wondrous near-life-forms on the fringe of the familiar, like a person in a dream who resembles, but is always a little askance from, someone you know in waking life.

Looking at these unliving plants, you are at once aware of their humble artificial origins and aware of that crowning glory of nature — consciousness, with its fathomless depths of creativity, capable of such ecstatically imaginative transformations.