But my favorite part of the story is that Boullée found his formative inspiration, not only for the Newton cenotaph and but for his entire creative philosophy, in an unusual encounter with trees — those profoundest of teachers.

His ultimate satisfaction was not the reception or execution of his designs, but the inexhaustible source of their inspiration — the elemental wellspring of the creative impulse behind all art and all science, that richest and readiest reward of our aliveness:

He attempted, more than that, to honor Newton on his own terms, by the essence of his genius:

No idea exists that does not derive from nature… It is impossible to create architectural imagery without a profound knowledge of nature: the Poetry of architecture lies in natural effects. That is what makes architecture an art and that art sublime.

In a sentiment evocative of another pioneer’s lamentation — Harriet Hosmer’s astute remark that “if one knew but one-half the difficulties an artist has to surmount… the public would be less ready to censure him for his shortcomings or slow advancement” — Boullée wrote of his critics:

No one is more exacting than a man who is not conversant with a given art for he is unable to imagine all the difficulties the artist has to overcome.

This was the moment of Boullée’s artistic awakening — that moment of revelation when, as Virginia Woolf wrote in her exquisite account of her own artistic awakening, something lifts “the cotton wool of daily life” and we see the familiar world afresh. Boullée recounted:

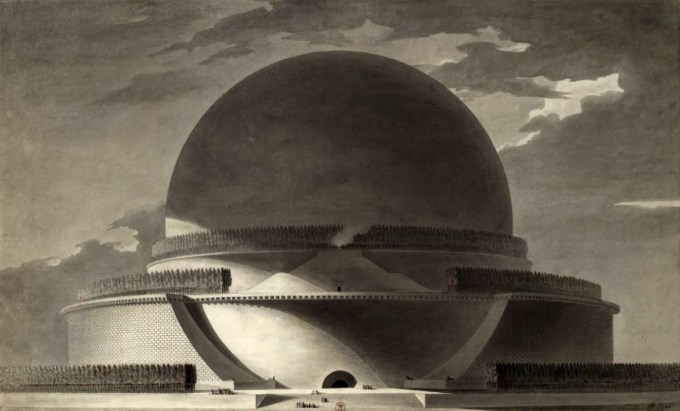

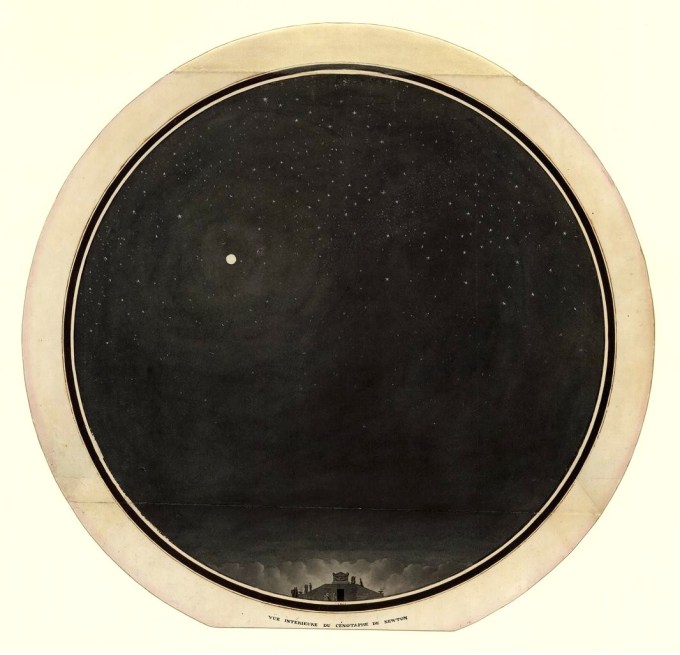

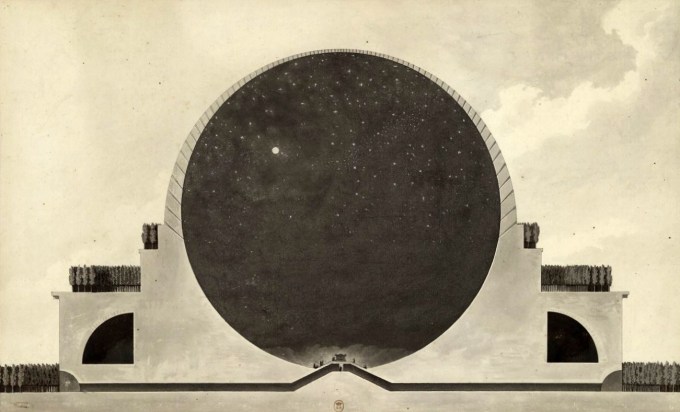

At a time long before readily available electric light and light-projection, he leaned on Newton’s optics to envision something that was part Stonehenge and part Hayden Planetarium. A century and a half before the first modern planetarium dome, Boullée dotted the black interior of his dome with an intricate arrangement of tiny holes reflecting the positions of the constellations and the planets, streaming in daylight to create an enchanting nightscape inside. But unlike the modern counterpart, Boullée’s was a reversible planetarium — at night, the sole spherical light would irradiate the tiny holes from the other direction, making the dome appear as a self-contained universe if viewed from above. This, lest we forget, was the golden age of aeronautics, when hot-air balloons first defied gravity to lift the human animal into the sky.

Symmetry… is what results from the order that extends in every direction and multiplies them at our glance until we can no longer count them. By extending the sweep of an avenue so that its end is out of sight, the laws of optics and the effects of perspective given an impression of immensity; at each step, the objects appear in a new guise and our pleasure is renewed by a succession of different vistas. Finally, by some miracle which in fact is the result of our own movement but which we attribute to the objects around us, the latter seem to move with us, as if we had imparted Life to them.

He called this new architecture “the architecture of shadow.” His vision for Newton’s cenotaph was its grand testament:

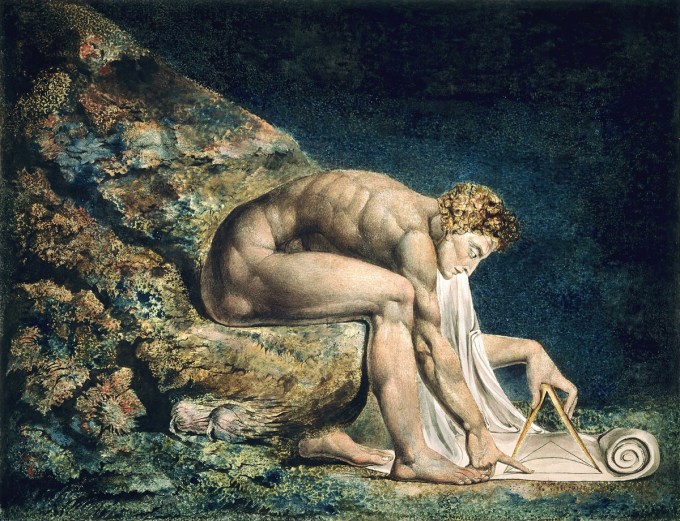

Nineteen years after the publication of Isaac Newton’s epoch-making Principia — in England, in Latin — the prodigy mathematician Émilie du Châtelet set out to translate his ideas into her native French, making them more comprehensible in the process. Her more-than-translation — which includes several of her mathematical corrections and clarifications of Newton’s imprecisions, and which remains the only comprehensive edition in French to this day — popularized his ideas in France and, from this epicenter of the Enlightenment, spread them centripetally throughout the rest of the Continent, rendering Newton himself an emblem of the Enlightenment the sweep of which he never lived to see.

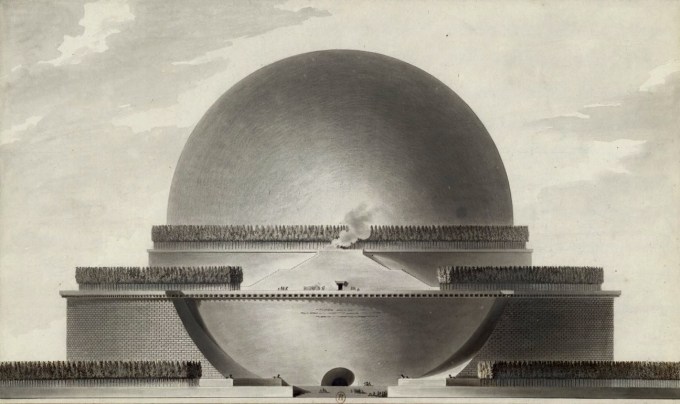

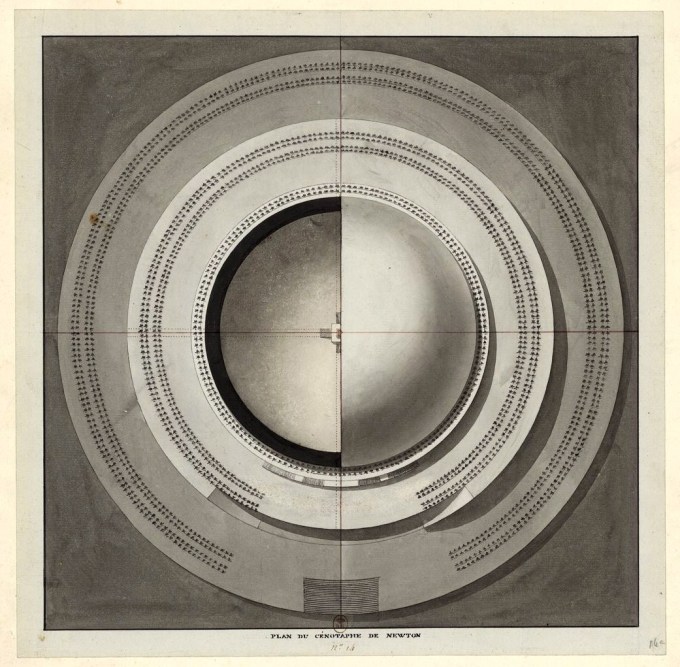

And so Boullée predicated his cenotaph for Newton on an enormous sphere that would convey his ultimate intent for the temple — to arouse in the visitor’s soul “feelings in keeping with religious ceremonies,” a sense of grandeur leaving them “moved by such an excess of sensibility… that all the faculties of our soul are disturbed to such an extent that we feel it is departing from our body” — an effect always best achieved not by an enormity of sheer size and space but by a considered contrast of scales. No building, he observed, “calls for the Poetry of architecture” more than a memorial to the dead. Believing that architecture, like all art, should ultimately serve to enlarge our sense of aliveness, and that we are never more alive than when we are rooted in our creaturely senses, Boullée insisted that the key to this sense of grandeur lies in applying the principles of nature’s mathematics with poetic subtlety — the principles laid bare in the Principia, the principles that “derive from order, the symbol of wisdom.” He wrote:

Too visionary for its era, the cenotaph was never built, but Boullée’s ink-and-wash drawings circulated widely in the final decade of his life, eliciting both gasping admiration and merciless derision — the fate of the true visionary. With the publication of his impassioned and insightful writings nearly two centuries after his death, translated by Helen Rosenau, his vision went on to inspire generations of modern artists and architects with a new way of thinking about the poetry of public spaces and the relationship between nature and human creativity.

The real talent of an architect lies in incorporating in his work the sublime attraction of Poetry.

The artist… is always making discoveries and spends his life observing nature.

While governed by the credo that “our buildings — and our public buildings in particular — should be to some extent poems,” Boullée also believed that science could magnify the poetry of public spaces, which must at bottom reflect the principles of the grand designer: Nature. A century before the teenage Virginia Woolf wrote that “all the Arts… imitate as far as they can the one great truth that all can see,” Boullée insisted:

O Newton! With the range of your intelligence and the sublime nature of your Genius, you have defined the shape of the earth; I have conceived the idea of enveloping you with your discovery… your own self. How can I find outside you anything worthy of you?

A sphere is, in all respects, the image of perfection. It combines strict symmetry with the most perfect regularity and the greatest possible variety; its form is developed to the fullest extent and is the simplest that exists; its shape is outlined by the most agreeable contour and, finally, the light effects that it produces are so beautifully graduated that they could not possibly be softer, more agreeable or more varied. These unique advantages, which the sphere derives from nature, have an immeasurable hold over our senses.

I attempted to create the greatest of all effects, that of immensity; for that is what gives us lofty thoughts as we contemplate the Creator and give us celestial sensations.

Architecture in the modern sense was then a young art, because the art-science of perspective was so novel. Newton’s optics, derived directly from the laws of nature, had revolutionized it all. Boullée came to define architecture as “the art of creating perspectives by the arrangement of volumes,” but a highly poetic art:

The mass of objects stood out in black against the extreme wanness of the light. Nature offered itself to my gaze in mourning. I was struck by the sensations I was experiencing and immediately began to wonder how to apply this, especially to architecture. I tried to find a composition made up of the effect of shadows. To achieve this, I imagined the light (as I had observed it in nature) giving back to me all that my imagination could think of. That was how I proceeded when I was seeking to discover this new type of architecture.

One evening, heavy with grief, Boullée went for a walk along the edge of a forest. Under the moonlight, he noticed his shadow. He had seen his shadow a thousand times before, but the peculiar lens of his psychic state rendered it entirely new — a living artwork of “extreme melancholy.” Looking around, he saw the shadows of the trees in this new light, too, etching onto the ground the profound drama of life. The entire scene was suddenly awash in “all that is sombre in nature.” He had seen the state of his soul mirrored back by the natural world, as we so often do in those rawest moments when we are stripped to the base of our being, grounded into our creaturely senses.

It is light that produces impressions which arouse in us various contradictory sensations depending on whether they are brilliant or sombre. If I could manage to diffuse in my temple magnificent light effects I would fill the onlooker with joy; but if, on the contrary, my temple had only sombre effects, I would fill him with sadness. If I could avoid direct light and arrange for its presence without the onlooker being aware of its source, the ensuing effect of mysterious daylight would produce inconceivable impression and, in a sense, a truly enchanting magic quality.

In a further homage to Newton’s legacy, with Boullée regarded as a “divine system” of laws, he chose to suspend a sole spherical lamp over the tomb as the only decoration in the entire monument — anything else, he felt, would be “committing sacrilege.” The contrast of scales — the smaller sphere of the lamp inside the enormous sphere of the building — would dramatize the contrast of light and shadow, just as the moonlight had done that fateful night of artistic revelation by the trees. This would give the visitor the sense that they are “as if by magic floating in the air, borne in the wake of images in the immensity of space.” Boullée considered the play of light the vital element in this enchantment:

Not long after Du Châtelet’s untimely death, her legacy reached one of her most gifted compatriots — the visionary architect Étienne-Louis Boullée (February 12, 1728–February 4, 1799), who fell under Newton’s spell. Determined to honor Newton with a worthy cenotaph — a memorial tomb for a person buried elsewhere — he designed a sphere 500 feet in diameter, taller than the Pyramids of Giza, nested into a colossal pedestal and encircled by hundreds of cypress trees, giving it the transfixing illusion of being both half-buried into the Earth and hovering unmoored from gravity. It was also, in essence, the world’s first domed planetarium design.

The cenotaph was a touching gesture in the first place — a Frenchman honoring a genius born of and interred in England, a nation with which Boullée’s own had been in near-ceaseless war for centuries, with those tensions at an all-time high at the time of his design, thanks to the American Revolutionary War. Doubly touching was his choice of a sphere: One of Newton’s most revolutionary contributions — the mathematical inference that because gravity is weaker at the equator, the shape of the Earth must be spherical — had defied France’s greatest son, René Descartes, who maintained that the Earth was egg-shaped. When Boullée was still a boy, a young Frenchman — Émilie du Châtelet’s mathematics tutor — had joined a perilous Arctic expedition to prove Newton correct. Two centuries later, in the wake of the world’s grimmest war yet, a queer Quaker Englishman would do the same, risking his life to defend the epoch-making theory of a German Jew — the theory of relativity that ultimately subverted Newton. Another world war later, Einstein himself would appeal to what he called “the common language of science” — that truth-seeking contact with nature and reality that transcends all borders and all nationalisms, the impulse that animated Boullée’s bold homage to Newton.

The poetry of architecture, he argued, resides in using perspective and light in such a way that “our senses are reminded of nature.” He interpreted the laws of nature, as clarified by Newton’s optics and mathematics, to intimate that no shape embodies this serenade to the senses with greater power and precision than the sphere: