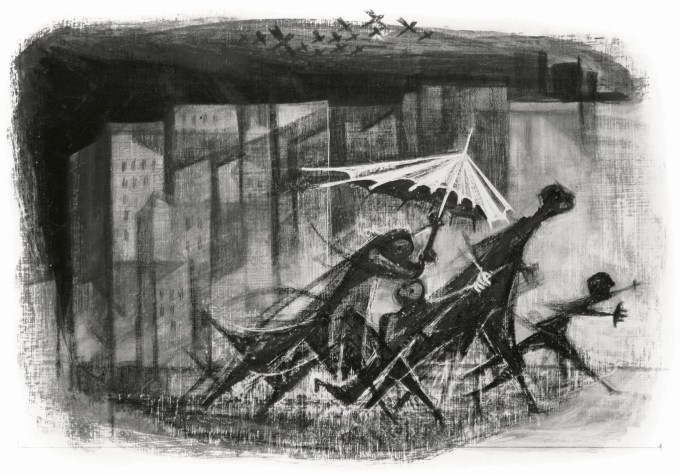

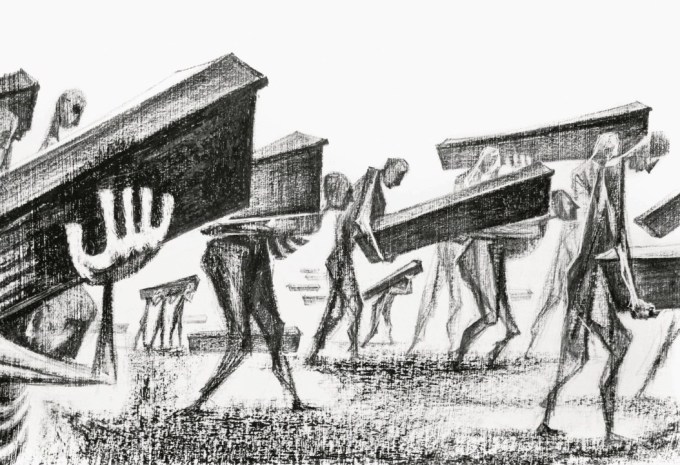

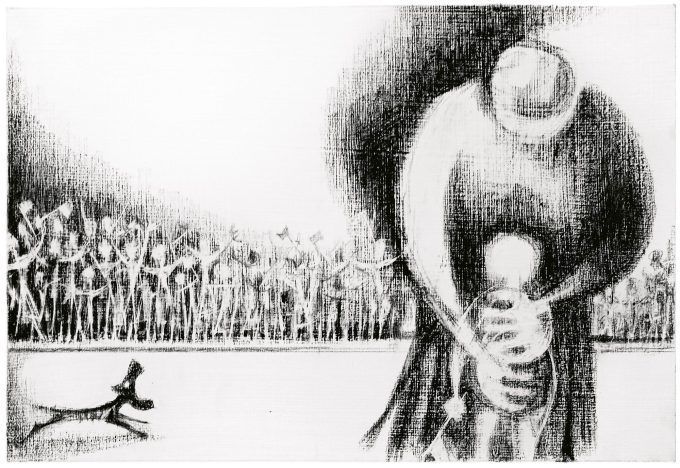

When he returned to New York with a wounded body and a scarred soul, he spent six months recovering at the VA hospital, then poured his surviving spirit into a stirring narrative suite of fifty-five drawings titled The Parade — a wordless, intensely emotional, consummately illustrated black-and-white charcoal meditation on the grim and abiding paradox of armed antagonism: that every war appeals to some primal part of the human spirit in order to gain its destructive momentum, and every war ends up destroying what is most buoyant and beautiful in that spirit.

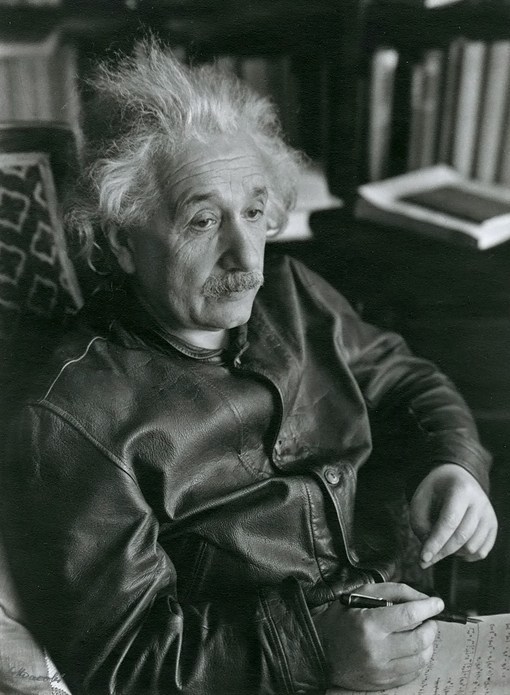

Einstein, who had spent the years between the two wars making an emphatic case for the interconnectedness of our fates and corresponding with Freud about violence and human nature, saw The Parade — unclear how, but very probably through the trailblazing photographer Lotte Jacobi, who was soon to exhibit them in her New York gallery. Einstein had sat for her more than a decade earlier and remained in touch.

It is true that it is utterly wrong and disgusting if some direction of thought and expression is forced upon the artist from the outside. But strong emotional tendencies of the artist himself have often given birth to truly great works of art. One has only to think of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and Daumier’s immortal drawings directed against the corruption in French politics of his time. Our time needs you and your work!

“Tyrants always fear art because tyrants want to mystify while art tends to clarify,” Iris Murdoch wrote in her arresting 1972 address on art as a force of resistance. “Those who tell you ‘Do not put too much politics in your art,’” Chinua Achebe told James Baldwin in their superb forgotten conversation at the close of that decade, “are the same people who are quite happy with the situation as it is… What they are saying is don’t upset the system.”

In consonance with his contemporary and fellow humanist Anaïs Nin’s ardent case for the centrality of emotional excess in creativity — “great art was born of great terrors, great loneliness, great inhibitions, instabilities, and it always balances them,” she wrote to a seventeen-year-old aspiring author whom she was mentoring — Einstein adds:

Couple with another Nobel-winning Albert, Camus, on the artist as a voice of resistance and an instrument of freedom, then revisit Adrienne Rich on the political power of poetry.

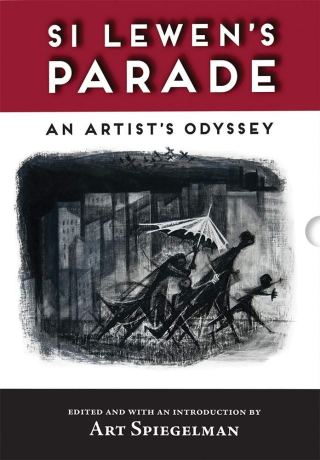

And yet despite how stirred those who saw it were by Lewen’s work, it fell into obscurity until it was rediscovered more than half a century later and resurrected in the final year of Lewen’s life in the stunning accordion volume Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey (public library), envisioned and edited by Art Spiegelman. It opens with the letter Einstein wrote to Lewen on August 13, 1951 — his most direct and impassioned statement on the political power of art:

A generation earlier, in the final years of his life, Albert Einstein sat down at his desk in Princeton, New Jersey, to compose a letter of consonant sentiment — a stirring letter of appreciation and assurance to the Polish Jewish artist Si Lewen (November 8, 1918–July 25, 2016), who had just quietly released a staggering work of art and resistance.

Lewen was still a teenager when his family fled to America as Hitler usurped power. When he arrived in New York, he was at first elated at the prospect of a new life full of art and free of persecution. He began taking drawing classes and going to the Metropolitan Museum every day. But when an antisemitic policeman beat him nearly to death, the terrifying thought that he would never be free from bigoted brutality and that the life of art could never be separate from the troubled life of the world drove him to a suicide attempt. And yet, like Lincoln, Lewen rose above the self-destructive impulse and turned the darkness into a motive force for action, for revising this broken and brutal world with his particular light.

Born days before Armistice Day, Si was five when he decided to become an artist — or rather (as such elemental self-awarenesses tend to bubble up) when he knew that he was one. In those formative years, his family fled from place to place as the situation for Jews in Europe was darkening by the minute. During a period of refuge in Berlin, while ostracized and bullied at school for being Jewish, he began receiving his first formal art lessons from a disciple of Paul Klee’s. His young imagination and his understanding of the world were being imprinted as much by his refuge in art as by the thickening political atmosphere of animosity that would soon erupt into the world’s grimmest war yet.

It has often been said that art should not be used to serve any political or otherwise practical goals. But I could never agree with this point of view.

Lewen died days before Spiegelman’s gorgeous resurrection of The Parade was published, in the politically precipitous months leading up to the 2016 American election. He never lived to see the country that had given him refuge crumble into a republic of racism and xenophobia for four years, but also never lived to see the redemption of the republic in the subsequent election of a President who, in another time and another place, would have perished in a concentration camp.

He enlisted in the American Army, in a secret intelligence unit of German-speaking immigrants who were flown into Germany for the invasion of Normandy that backboned D-Day, the liberation of France, and the ultimate defeat of the Nazis. There to do translation work and to illustrate posters and pamphlets rallying the troops, Lewen walked into one of the major concentration camps the day after it was liberated and saw what had happened to countless people who looked like him, who spoke the same language and dreamt kindred dreams — saw the would-be destiny he had narrowly escaped by making it to America as a refugee.

I find your work The Parade very impressive from a purely artistic standpoint. Furthermore, I find it a real merit to counteract the tendencies towards war through the medium of art. Nothing can equal the psychological effect of real art — neither factual descriptions nor intellectual discussion.