One definition of love may be that the world becomes unimaginable without the person you love. This is what makes the death of a loved one nothing less than world-shattering. But from the vantage point of the brain, a death is simply a sudden and inexplicable absence — the total erasure of the person from the mental model of the living world. In fMRI studies, the same brain circuitry lights up whenever we experience prolonged absence, even if it is not permanent — the magnitude may be different, but the neurophysiology of the heartache is the same. Every perceived abandonment is a scale model of grief.

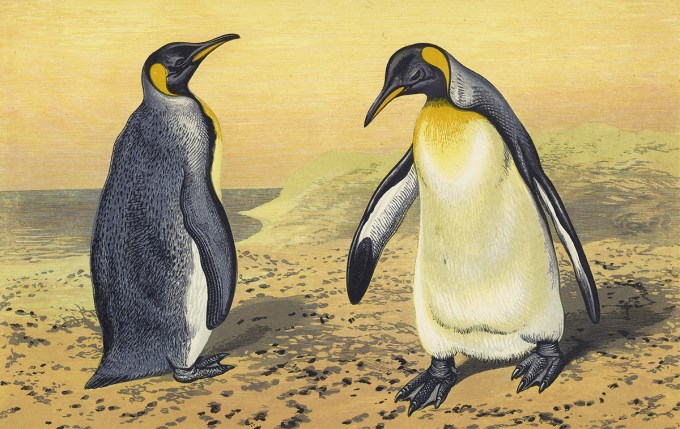

In a lovely aside in her altogether fascinating exploration of the science of grief and healing, neuroscientist and fMRI pioneer Mary-Frances O’Connor details the astonishing feats of faith that penguins perform when one parent ventures far out into the inhospitable Antarctic ocean on a four-month hunt for food while the other remains in the nest to incubate the egg, fasting the entire time, with no guarantee of his partner’s return.

With an eye to the sweet true story of Tango — the baby penguin hatched from an abandoned egg and raised by a same-sex penguin couple at the Central Park Zoo in the 1990s: a different act of survivalist faith against all odds — O’Connor writes:

Nested within this remarkable phenomenon is yet another mirror held up to our habitual hubris. Even after we began dismantling the damaging Cartesian delusion that all the other animals are mere automata and we alone are capable of feeling, we still placed at the center of our species identity the ability to remember the past and plan for the future. And yet in this too we are far from alone, as the penguins so touchingly remind us. Each time we have thought ourselves superior and singular along some axis of ability, the rest of nature and those willing to notice it — also called scientists — have humbled us into reality: We thought ourselves the only animals to use tools, until Jane Goodall toppled epochs of dogma with her revolutionary work with the chimpanzees at Gombe; we thought ourselves this planet’s most complex consciousness, but along came the octopus. At every turn comes surging more evidence that, in Sy Montgomery’s poetic words, “our world, and the worlds around and within it, is aflame with shades of brilliance we cannot fathom… far more vibrant, far more holy, than we could ever imagine.”

In navigating this universally trying human experience of weathering the miniature griefs of abandonment, we find an improbable teacher in penguins — a species that also forms monogamous pair-bonds, which can last a mating season or a lifetime.

Keeping these non-permanent absences from shattering our inner world demands of us extraordinary mental acrobatics that override the physical evidence of the absence with mental reminders that the loss is not definitive. Another word for this is faith — the brain’s built in airbag against heartbreak.

Regardless of who the parents are, the key here is that one parent must persist in the belief, during a very long absence in the Antarctic, that their partner will return with food. If one parent decides that their partner will not return, and goes to the sea to fish, then the egg fails to hatch, or the chick dies. Those penguins who persist in the belief their partner will return, and wait for them, are far more successful. In [The March of the Penguins] we see that among thousands of penguins, the returning mother finds her partner by recognizing his very specific call. It is a remarkable phenomenon, with these animals overcoming seemingly endless odds.

Complement the penguins’ singular triumph of faith with a human counterpart in Kahlil Gibran on the courage to weather the uncertainties of love, then revisit O’Connor’s fascinating work on the neuropsychology of love, loss, and resilience.