More than anything, we lie to ourselves. Peeled back far enough, even the most layered self-delusion springs from the same source — our illusion of free will amid a world in which, at the most basic level of reality, we control none of the fundamental forces and therefore have extremely limited agency in events. As the precocious teenage Sylvia Plath understood, our latitude of free movement in life is paralyzingly limited “from birth by environment, heredity, time and event and local convention”. In such a reality, choice is only a narrative, and a retroactive one at that — it is the story we tell ourselves, in the vanity-light of hindsight, about why our lives went one way and not another.

What a queer gamble our existence is. We decide to do A instead of B and then the two roads diverge utterly and may lead in the end to heaven and to hell. Only later one sees how much and how awfully the fates differ. Yet what were the reasons for the choice? They may have been forgotten. Did one know what one was choosing? Certainly not.

Looking back on his life, the elderly playwright reflects on his own art and its relation to life itself:

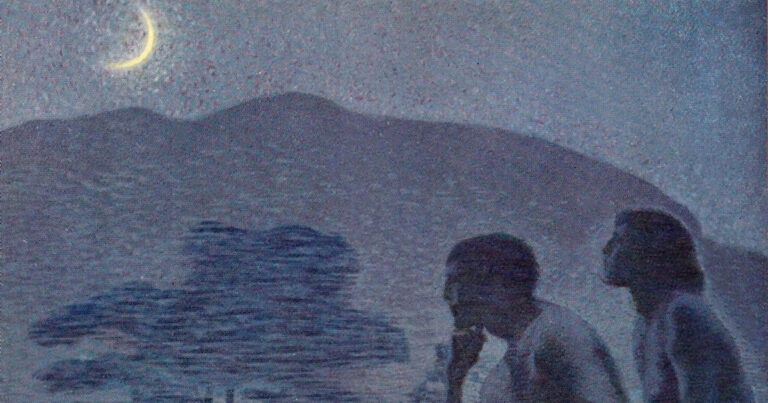

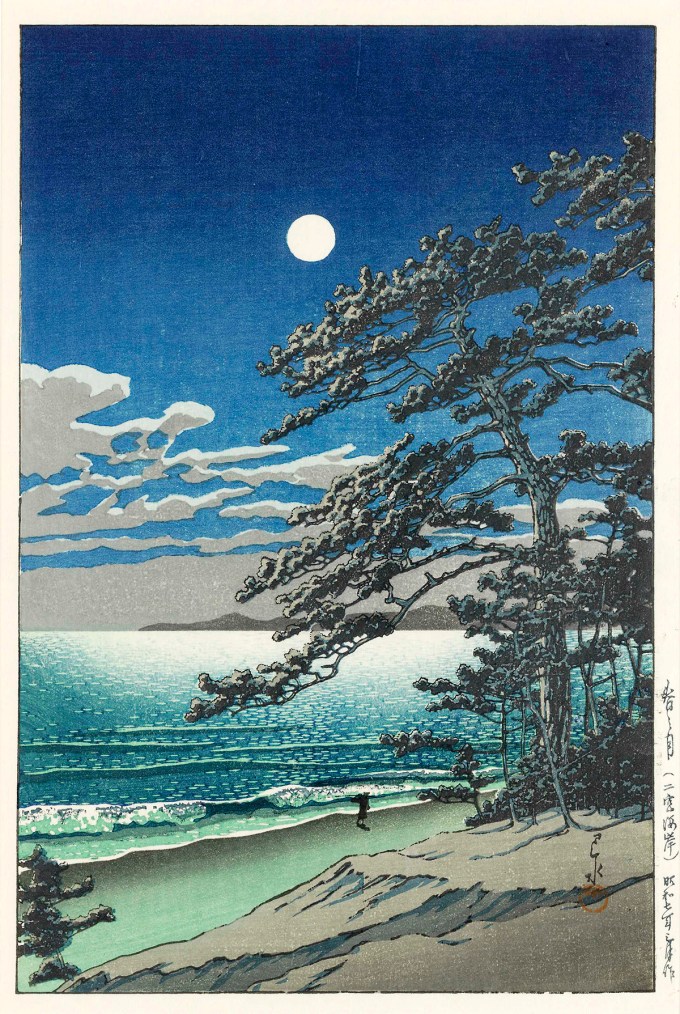

But here is where we do have choice: In accepting a hazy and uncertain reality beyond our control, we can also refuse to resign ourselves to being victims of it — the sort of adaptation Octavia Butler held up as the highest measure of intelligence and integrity. We can recognize that life is much more interesting as a process of continual presence than as an acted drama; that the world is much more interesting as a shoreline than as a stage — for it is at the living shore that we witness, as Richard Feynman did, “ages upon ages” unfolding into the wonder of life; at the shore that we are humbled, as Rachel Carson was, by “our place in the stream of time and in the long rhythms of the sea… in which there is no finality, no ultimate and fixed reality”; at the shore that we finally accept the most elemental fact of our lives: There is no final act — only shoreless seeds and stardust.

Loose ends can never be properly tied, one is always producing new ones. Time, like the sea, unties all knots. Judgements on people are never final, they emerge from summings up which at once suggest the need of a reconsideration. Human arrangements are nothing but loose ends and hazy reckoning, whatever art may otherwise pretend in order to console us.

A subset of the illusion of choice is the illusion of closure — the alluring but ultimately vain idea that, as life lives itself through us in ways far beyond our control, in a complex and by definition ever-fraying tapestry of story-lines, we can tease out any one narrative thread neatly enough to tie it into a complete and permanently valid conclusion. Murdoch dispels the vanity:

Echoing James Baldwin’s exquisite lament about the illusion of choice, Murdoch writes:

In literature, when a storyline involves victim and a persecutor, we call it a drama. In life, most acts of aggression or complaint (which are two sides of the same coin: the emotional currency of existential malcontentment), most tantrums thrown by otherwise reasonable adults, most blamethirsty fingers pointed at some impartial reality, involve the self-victimization of drama. People prone to drama have not only cast themselves as victims of a perpetrator in a plot, but have tacitly conceded that there is a plot, which presupposes a playwright — some external entity scripting the story in which they feel done unto. The person self-cast into a drama is resigned to being a character, insentient to Joan Didion’s fundamental law of having character: “Character — the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life — is the source from which self-respect springs.” Wherever there is drama, there is a deficiency of self-respect and too shallow a well of self-knowledge.

We are such inward secret creatures, that inwardness the most amazing thing about us, even more amazing than our reason. But we cannot just walk into the cavern and look around. Most of what we think we know about our minds is pseudo-knowledge. We are all such shocking poseurs, so good at inflating the importance of what we think we value. The heroes at Troy fought for a phantom Helen… Vain wars for phantom goods… People lie so… though in a way, if there is art enough it doesn’t matter, since there is another kind of truth in the art.

Emotions really exist at the bottom of the personality or at the top. In the middle they are acted. This is why all the world is a stage.

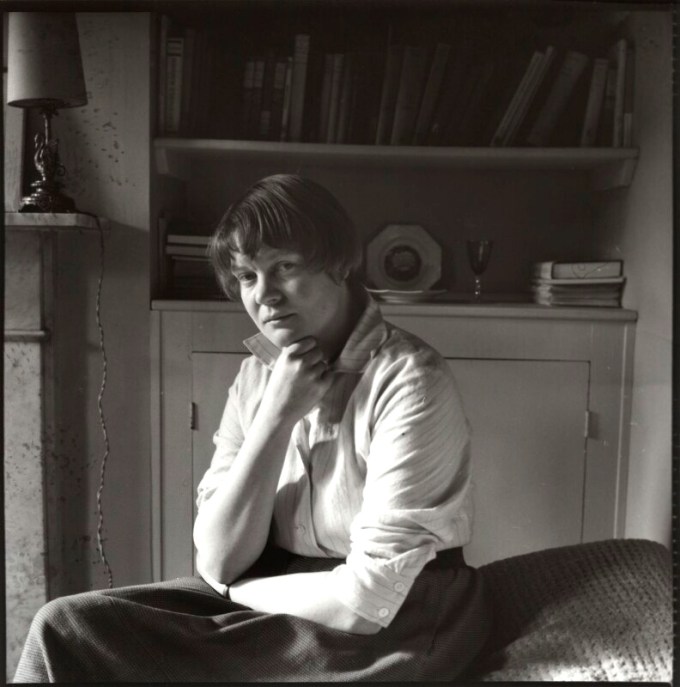

Murdoch’s entire body of work, from philosophy to fiction, can be thought of as one cohesive inquiry into the meaning of goodness and the meaning of love, lensed through the meaning-machinery of art. She understood uniquely that we act out the messy middle of emotion because it is often too complex, contradictory, and category-defying for us to know what we are really feeling. Perennially half-opaque to ourselves, we feign surety and confidence in our reasons. Unwilling to fully live into what we are — anxious and uncertain creatures, tender and terrified throughout so much of life — we act ourselves into being, taking the stage costumed in false certitudes.

The ways in which we are all susceptible to drowning ourselves into drama, and what it takes to float free, is what Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) explores in her subtle, splendid 1978 novel The Sea, the Sea (public library) — the story of a talented but complacent playwright approaching the overlook of life, who is ultimately overcome by his tragic flaw: Despite his obsessive self-reflection (or perhaps precisely because of it), his egotism ultimately eclipses his creative spirit — that brightest and most generous part of us, the part rightly called our gift, the part that extends the outstretched hand of sympathy and wonder we call art and invites, in Iris Murdoch’s lovely phrase, “an occasion for unselfing.”

As Murdoch’s protagonist sets out to write his memoirs — those sad shallows of literature, where art drifts to die as vain self-obsession — his cousin and boyhood playmate, now an old men himself, urges him to allot ample room for the eternal subject of human vanity, which renders us blinder to reality and more opaque to ourselves than any of our other confusions: