The preferred, most efficient, highest-order form of energy transfer (the premier way for a scene to advance the story in a non-trivial way) is for a beat to cause the next beat, especially if that next beat is felt as essential, i.e., as an escalation: a meaningful alteration in the terms of the story.

A story is able to reach that honest part of the mind and move it only by dignifying the reading mind as such. A generation before Saunders, E.B. White — one of the most singular and splendid storytellers of all time, and one of the most beloved children’s book authors — insisted that in order to write well for any reader, but especially for that most alert and honest-minded of readers, the child, “you have to write up, not down.” (This I consider also the key to great science-storytelling, and especially to the rare intersection of the two.) Defining a story as “an ongoing communication between two minds,” Saunders observes:

We move through a storied world as living stories. Every human life is an autogenerated tale of meaning — we string the chance-events of our lives into a sensical and coherent narrative of who and what we are, then make that narrative the psychological pillar of our identity. Every civilization is a macrocosm of the narrative — we string together our collective selective memory into what we call history, using storytelling as a survival mechanism for its injustices. Along the way, we hum a handful of impressions — a tiny fraction of all knowable truth, sieved by the merciless discriminator of our attention and warped by our personal and cultural histories — into a melody of comprehension that we mistake for the symphony of reality.

[…]

This transfer of energy, this transmutation of understanding, is, of course, the mystique and mechanism by which all art moves us — a story, a song, a poem, a painting. Learning to be present with it, to notice the pulses that move the mind into thought and feeling, refines our ability to attend not only to art but to the world — for, as neuroscientist Christof Koch readily reminds us, “consciousness is the central fact of your life.” Saunders writes:

[…]

[…]

[…]

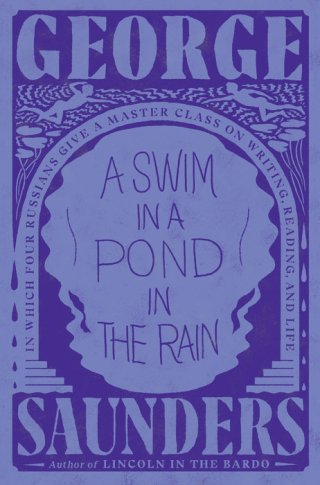

That is what George Saunders explores throughout A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life (public library) — his wondrous investigation of what makes a good story (which is, by virtue of Saunders being helplessly himself, a wondrous investigation of what makes a good life) through a close and contemplative reading of seven classic Russian short stories, examined as “seven fastidiously constructed scale models of the world, made for a specific purpose that our time maybe doesn’t fully endorse but that these writers accepted implicitly as the aim of art — namely, to ask the big questions.” Questions like what truth is and why we love. Questions like how to live and how to make meaning inside the solitary confinement of our mortality. Questions like:

Second, the extent to which the writer has learned to make causality.

A story is a series of incremental pulses, each of which does something to us. Each puts us in a new place, relative to where we just were… We watch the way the deep, honest part of our mind reacts to it. And that part of the mind is the one that reading and writing refine into sharpness.

A story is a series of incremental pulses, each of which does something to us. Each puts us in a new place, relative to where we just were… We watch the way the deep, honest part of our mind reacts to it. And that part of the mind is the one that reading and writing refine into sharpness.

A story is a series of incremental pulses, each of which does something to us. Each puts us in a new place, relative to where we just were… We watch the way the deep, honest part of our mind reacts to it. And that part of the mind is the one that reading and writing refine into sharpness.

A story is a series of incremental pulses, each of which does something to us. Each puts us in a new place, relative to where we just were… We watch the way the deep, honest part of our mind reacts to it. And that part of the mind is the one that reading and writing refine into sharpness.

Great storytelling plays with this elemental human tendency without preying on it. Paradoxically, great storytelling makes us better able not to mistake our compositions for reality, better able to inhabit the silent uncertain spaces between the low notes of knowledge and the shrill tones of opinion, better able to feel, which is always infinitely more difficult and infinitely more rewarding than to know.

With an eye to how a story makes its meaning — small structural pulses appearing in sequence, at speed, to give rise to a set of expectations and resolutions — he writes: