All of this — the dandelion, the insistence on wonder as the sieve for meaning — reminded me of a some passages by G.K. Chesterton (May 29, 1874–June 14, 1936) — philosopher, impassioned early eugenics opponent, prolific author of several dozen books, several hundred poems and short stories, and several thousand essays — from The Autobiography of G.K. Chesterton (public library).

How to awaken to this miraculousness and begin to make meaning is, of course, the great creative challenge of life.

The primary problem for me, certainly in order of time and largely in order of logic… was the problem of how men could be made to realise the wonder and splendour of being alive, in environments which their own daily criticism treated as dead-alive, and which their imagination had left for dead.

I had from the first an almost violently vivid sense of those two dangers; the sense that the experience must not be spoilt by presumption or despair… I asked through what incarnations or prenatal purgatories I must have passed, to earn the reward of looking at a dandelion… [or a] sunflower or the sun… But there is a way of despising the dandelion which is not that of the dreary pessimist, but of the more offensive optimist. It can be done in various ways; one of which is saying, “You can get much better dandelions at Selfridge’s,” or “You can get much cheaper dandelions at Woolworth’s.” Another way is to observe with a casual drawl, “Of course nobody but Gamboli in Vienna really understands dandelions,” or saying that nobody would put up with the old-fashioned dandelion since the super-dandelion has been grown in the Frankfurt Palm Garden; or merely sneering at the stinginess of providing dandelions, when all the best hostesses give you an orchid for your buttonhole and a bouquet of rare exotics to take away with you. These are all methods of undervaluing the thing by comparison; for it is not familiarity but comparison that breeds contempt. And all such captious comparisons are ultimately based on the strange and staggering heresy that a human being has a right to dandelions; that in some extraordinary fashion we can demand the very pick of all the dandelions in the garden of Paradise; that we owe no thanks for them at all and need feel no wonder at them at all; and above all no wonder at being thought worthy to receive them.

With an eye to the absurdity of pessimism as a life-orientation, given the astonishing good luck of existing at all in a universe where the probability is overwhelmingly against it, he adds:

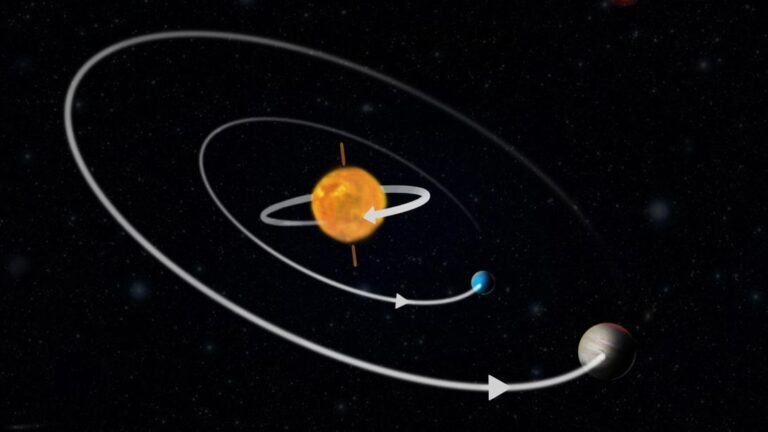

These are the thoughts coursing through this temporary constellation of consciousness as I pause at the lush mid-June dandelion at the foot of the hill on my morning run — the dandelion, now a fiesta of green where a season ago the small sun of its bloom had been, then the ethereal orb of its seeds, now long dispersed; the dandelion, existing for no better reason than do I, than do you — and no worse — by the same laws of physics beyond meaning: these clauses of exquisite precision punctuated by chance.

And so we get to the dandelion:

There is a myth we live with, the myth of finding the meaning of life — as if meaning were an undiscovered law of physics. But unlike the laws of physics — which predate us and will postdate us and made us — meaning only exists in this brief interlude of consciousness between chaos and chaos, the interlude we call life. When you die — when these organized atoms that shimmer with fascination and feeling — disband into disorder to become unfeeling stardust once more, everything that filled your particular mind and its rosary of days with meaning will be gone too. From its particular vantage point, there will be no more meaning, for the point itself will have dissolved — there will only be other humans left, making meaning of their own lives, including any meaning they might make of the residue of yours.

A century after Baudelaire observed that “genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will,” and a generation before Dylan Thomas insisted that “children in wonder watching the stars, is the aim and the end,” Chesterton looks back on his early life and how it fomented the animating ethos of his later life as a literary artist and thinker:

What was wonderful about childhood is that anything in it was a wonder. It was not merely a world full of miracles; it was a miraculous world.

Once Chesterton found the art through which to channel this blaze of astonishment, he found his writing “full of a new and fiery resolution to write against the Decadents and the Pessimists who ruled the culture of the age.” He reflects:

Find some kindred thought in this epochs-wide meditation on the flower and the meaning of life, starring Emily Dickinson, Michael Pollan, and the Little Prince, then revisit Roar Like a Dandelion — poet Ruth Krauss’s lost serenade to wonder, found and turned into a modern picture-book by artist Sergio Ruzzier.

And yet, somehow, against the staggering cosmic odds otherwise, we get to experience this sky, these trees, these colors, these loves we live. The recognition of this unbidden miracle of chance is the fundamental matter of meaning — the great awakening from the myth.

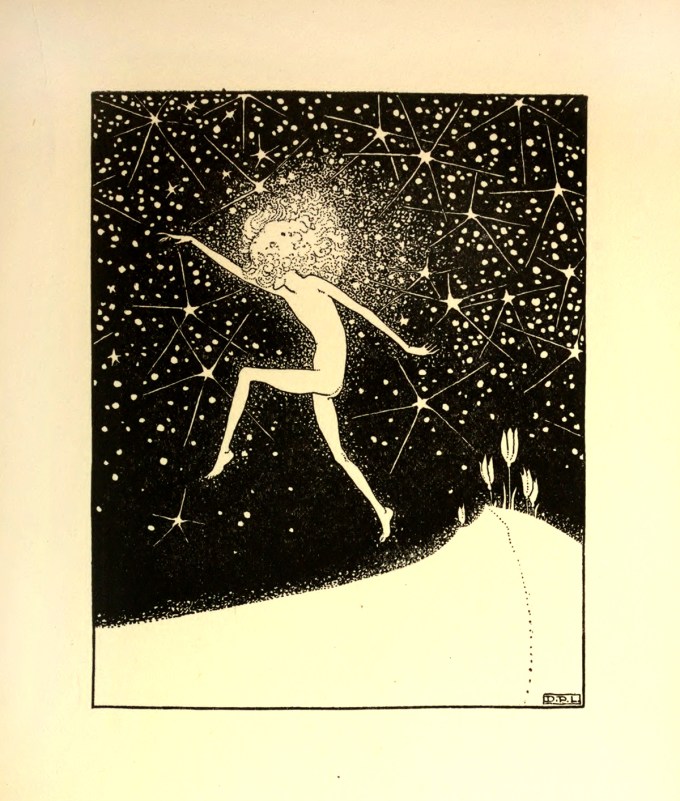

No man* knows how much he is an optimist, even when he calls himself a pessimist, because he has not really measured the depths of his debt to whatever created him and enabled him to call himself anything. At the back of our brains… [there is] a forgotten blaze or burst of astonishment at our own existence. The object of the artistic and spiritual life [is] to dig for this submerged sunrise of wonder; so that a man sitting in a chair might suddenly understand that he [is] actually alive, and be happy.